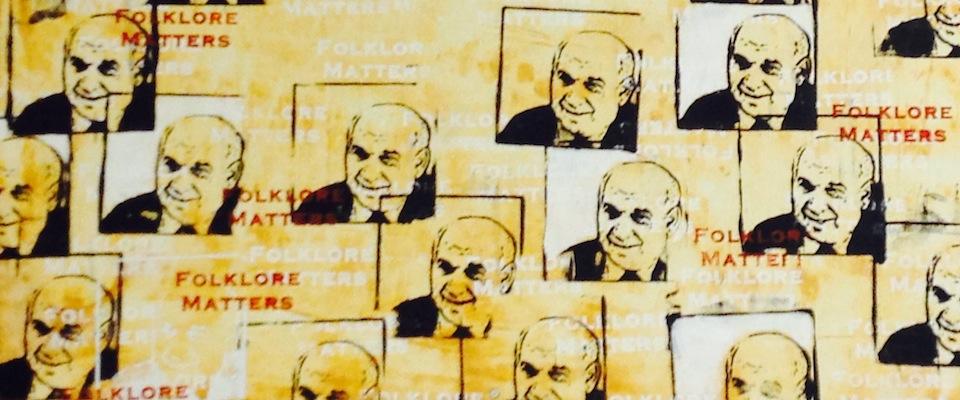

Legendary folklorist Alan Dundes took jokes to another level.

Alan Dundes died with a joke on his lips. At least, that’s one version of the story. This much is certain: The beloved Cal professor died unexpectedly in 2005, while lecturing. Dundes was a giant in the field of folklore scholarship, an inveterate collector of, and prolific publisher on, unrecorded tales, songs, and traditions. But the man who was sometimes called the Joke Professor had a particular affinity for humor.

Growing up in the suburbs of New York City, Dundes fell in love with the quips his father picked up on the commuter train and heard hundreds more during two years in the Navy. As a grad student, inspired in part by Freud’s collection of Jewish jokes, Dundes began gathering them for his doctoral dissertation. Once ensconced at Berkeley, he launched the Folklore Archive, which now holds over 500,000 items—including thousands of bits of humor collected by students enrolled in Dundes’s famous course, The Forms of Folklore.

A large man, known for his rapid speech and an endless rotation of baggy suits, white shirts, and dark ties, Dundes held court in office hours that were both intimidating and exhilarating. He brimmed with advice and insight but countenanced no sloppy scholarship. So singular a presence was he for students—some of whom called him “the Master” or simply “Himself”—that they collected their own Dundes folklore, known as Dundesiana. The Berkeley Folklore Archive even has a folder devoted to Dundes-inspired “latrinalia,” the bathroom wall scribblings he established as a legitimate object of study. One entry reads “Keep Alan Dundes working! Write graffiti!”

Dundes’s revolutionary contribution to the field, however, was not in gathering folklore but in analyzing it. “For him, being a folklorist was like being a scientist,” says Maria Teresa Agozzino, a folklore professor at Ohio State University who worked as Dundes’s assistant for eight years. To Dundes, collected scraps of folklore “were the hard data” of social mores and cultural trends, and jokes could be particularly illuminating.

Dundes turned a gimlet eye—often with a Freudian lens—to every brand of humor ranging from math jokes to light-bulb jokes, Gary Hart jokes to AIDS jokes, Muslim jokes to elephant jokes. The latter, for instance, he interpreted as veiled references to African Americans, a kind of humor code spawned by white anxiety over civil rights. He also saw a direct line running from what he believed was a German cultural obsession with scatological jokes, to the rise of Nazi fascism.

“Some people believe jokes and nursery rhymes and fairy tales are just harmless little stories that don’t mean anything,” Dundes told Jim Holt, author of the joke history Stop Me If You’ve Heard This. “But they’re not meaningless. And they’re not necessarily harmless, either.”

Digging out the meaning buried in off-color humor, Dundes knew, could cause offense. And offend he certainly did. His analysis of the “dead baby” joke cycle, which he linked to abortion’s emergence as a political issue, featured such universally disturbing examples as “What’s harder to unload, a truck full of bowling balls or a truck full of dead babies?” Answer: “Bowling balls. You can’t use a pitchfork with bowling balls.” It’s a revolting premise with an even more disgusting punch line, and Dundes cited such things ad nauseam. It wasn’t gratuitous. He insisted there was meaning to be mined from all jokes, no matter how crass or shallow.

“Nothing is so sacred, so taboo, or so disgusting that it cannot be the subject of humor,” he wrote in a paper analyzing Auschwitz jokes. “Indeed, it is precisely those topics culturally defined as sacred, taboo, or disgusting that tend to provide the principal grist for humor mills.”

Of course not everyone agreed that all jokes, no matter how offensive, deserved scholarly attention. Several publishers refused to print his work—notably his examinations of Holocaust jokes and his paper on Romanian political jokes, “Laughter Behind the Iron Curtain.” During his career, he was reportedly shouted down, pelted by audiences, and once draped in toilet paper while speaking. He is likely the only folklorist to ever receive a death threat, after a version of his classic 1978 paper “Into the Endzone for a Touchdown”—on the homoerotic subtext of American football terminology—appeared in Time magazine.

If you didn’t know the man, Dundes’s obsession with finding the dark shadings of id and superego in every punch line might suggest a certain humorlessness. Yet the thing about him that friends and former colleagues remember best was precisely his ability to make people laugh. Professor of Scandinavian, John Lindow still cracks up recalling Dundes’s story of falling overboard on his final day in the Navy. “He was,” Lindow says, “probably the funniest person I’ve ever known.”

“He could have had a career as a standup comedian and made a fortune,” insists Stanley Brandes, a professor of social cultural anthropology at Berkeley.

“Even though he’d been doing it for 30 years, he would make everybody feel like he hadn’t heard it before,” recalls Agozzino. “He was like a kid in a candy store. He never lost that infectious excitement.”

Dick Corten ’65, who took Dundes’s courses as an undergrad and was editor of The Pelican, remembers the lectures. “Everything was rapidfire. His badda-bing delivery, his citations of other scholars, his gallop through the material…. His energy level must have been extraordinarily high.” Partly due to the pace Dundes set, his classes tended to take most students “down a notch. A students to B, B to C, and so on” Corten says. “As entertaining as his lectures were, he wasn’t just an entertainer. That the material was diverting cut two ways. You couldn’t help but laugh, but then you had to grab the concept and remember what it meant.”

It was Jim Holt who wrote in Stop Me If You’ve Heard This that Dundes died “with a joke on his lips.” The Wikipedia entry on him reports only that his last words were, “But there are really only two uses for Marxist theory in folkloristics.” It’s tough to say whether that was meant as a setup or a serious point. In any case, the entry contains no citation. It’s just one more bit of Dundesiana for the archives.