Facing the Mountain: A True Story of Japanese American Heroes in World War II

By Daniel James Brown ’74

The great American novelist and Vietnam vet Tim O’Brien once insisted you could only tell a true war story if it embarrassed you. Daniel James Brown’s latest book, Facing the Mountain, begins with a truly shameful incident: As Japanese bombs pummel the naval bases and airfields at Pearl Harbor and frantic American service members fire anti-aircraft shells into the sky, a stray shell tears into a Japanese-language school, killing and injuring several children. It would not be the headline of December 7, 1941, but it was a harbinger of the complexities of the war to come.

Brown, a Berkeley alumnus, has made a name for himself in narrative nonfiction, particularly with his 2013 mega-bestseller The Boys in the Boat, a gripping account of the University of Washington rowing team that beat out Germany for the gold medal in the Nazi Olympics in Berlin. With Facing the Mountain, Brown now turns his attention to the war that followed.

Relying on exhaustive research, he charts the path of four Japanese American men, some of whom were deployed to fight in Europe while their families at home were locked away in internment camps (which Brown makes a point of calling “concentration camps”). In doing so, the book gives an unflinching account of how America turned on its own citizens. At the same time, it gives voice to a chorus of Americans rarely heard from, including Gordon Hirabayashi, the Seattle Quaker who spent years in court opposing the curfews and concentration camps as unconstitutional, and the men of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, which was mostly made up of Nisei (second-generation Japanese Americans) and was one of the most decorated U.S. Army units in history.

Brown is certainly not the first to chronicle this history. In 1957, John Okada essentially kicked off the Asian American literary tradition with No-No Boy, about an interned Japanese American man further incarcerated for refusing to fight for the United States in the war. More recently, Julie Otsuka’s 2002 bestseller When the Emperor Was Divine explores a Berkeley family upended by their sudden removal to a remote camp in Utah. What sets Brown’s project apart, perhaps, is its scope. To produce it, he relied heavily on the archives of Densho, a Seattle nonprofit devoted to preserving the stories of Japanese Americans imprisoned during World War II. The executive director of Densho, Tom Ikeda, makes it clear in his foreword that he views Facing the Mountain as a culmination of Densho’s efforts. Ultimately, what Brown provides with this book is an eminently readable synthesis of others’ war stories that rings with the embarrassment of truth.

—Hayden Royster

Bernoulli’s Fallacy

By Aubrey Clayton, Ph.D. ’08

Mathematician Aubrey Clayton lost his faith in probability as a grad student at Berkeley, when he made a lot of money betting on the NBA but couldn’t explain why. This “destabilizing epiphany” led him to reexamine fundamental notions about probability, and what he found—if true—is dire: a flaw baked into modern statistics, with ramifications for the sciences and the world at large.

In Bernoulli’s Fallacy (Columbia University Press), Clayton, a frequent contributor to the Boston Globe, capably guides the reader through the history of statistics, beginning with Jacob Bernoulli, the 17th-century Swiss mathematician widely considered the father of probability. Bernoulli posited that, given a large enough sample, one could make inferences with high certainty. This idea, which has animated statistics for more than 300 years, is wrong, argues Clayton. Bernoulli’s framework may help you correctly guess a dice roll, he says, but it’s inadequate for making real-world suppositions about more complex systems, like communities, disease, or the human brain.

The book is a polemic: In the war currently raging in statistics (who knew?) between “frequentists” and “Bayesians,” the author is squarely in the latter’s camp. In arguing his case, he paints a grim picture of the current state of scientific research, pointing to scores of false positives, mountains of baseless theories, and a well-publicized “crisis of replication,” particularly in the social sciences. His interest is not in tearing down science but rather in shoring it up. “In the coming decades,” he writes, “science will need defending. As it stands now, though, much of science needs defending from itself.”

—H.R.

Turntables

Directed by Latanya d. Tigner and Lashon Daley, M.A. ’15, Ph.D. ’21

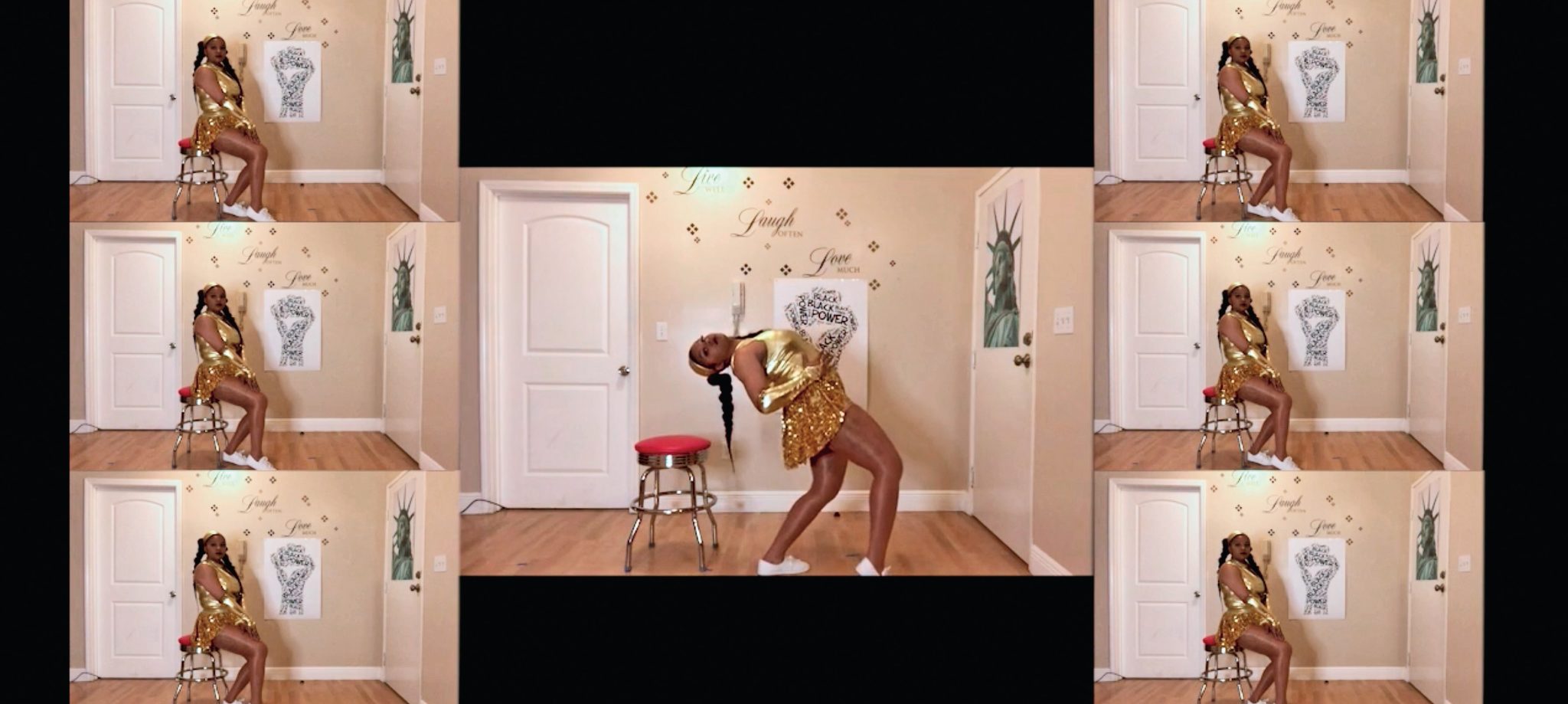

A 41-minute-long film from the Berkeley Dance Project, an annual production of the Department of Theater, Dance, and Performance Studies at Berkeley, Turntables focuses on the Bearettes, the first majorette-style dance team in the UC system.

The Bearettes’ dance style, also known as hip-hop majorette, began at historically Black colleges and universities in the ’60s. It combines high-step marching from Black college bands with movements from the West African, jazz, modern, and hip-hop traditions.

Shooting under pandemic conditions in both black and white and vibrant color, directors Latanya d. Tigner and Lashon Daley create a mise-en-scène that addresses the Civil Rights Movement and the challenges women of color still face in finding space to express themselves. Because of social distancing protocols, each dancer in the film performed in their own video conferencing space, but their movements come together on screen, gracefully in sync.

Turntables is free to stream on Vimeo until December 31.

—Gitanjali Poonia

Stay Prayed Up

Co-directed by Matt Durning, M.A. ’10

Gospel music, says Matt Durning, is “a force that is building and sustaining communities in a way that not a lot of things are in America today.” Durning is co-director of the new documentary film Stay Prayed Up, which follows the Branchettes, a Black gospel group from North Carolina, as they embark on recording their first live album.

This “church gospel noisy crew” features a lively cast with electrifying voices, including the band’s 82-year-old leader, Lena Mae Perry—a prominent force in sustaining the local Black community through faith, music, and companionship despite a life marked by tribulations. “With every hardship she endures, her clarity of purpose and unconditional love for others become stronger,” says Durning.

At the center of the film is the synergy between faith and music in building community and the power of something larger than yourself. “They’re compelled,” co-producer Phil Cook says in the film. “It’s down to their heels. It’s all over their body. It’s so much bigger than them. They will do this until they are no more.”

Stay Prayed Up premiered at Telluride in September and is currently on the festival circuit. Look for it to be more widely released in April 2022.

—Dhoha Bareche

The Pyrocene: How We Created an Age of Fire, and What Happens Next

By Stephen J. Pyne

“Earth alone holds fire,” author Stephen Pyne tells us at the outset of this slim and surprising volume from UC Press. “Among planets fire is as rare as life, and for the same reason: fire on Earth is a creation of the living world.” Even Earth, for most of its existence, did not have fire. There was lightning as an ignition source, but it took bacteria to create the oxygen, and plants to create the fuel necessary for combustion to occur some 420 million years ago.

The book takes its title from a term the author, a professor emeritus at Arizona State University and one of the world’s foremost experts on fire ecology, coined in 2015. It’s an alternate name for the more fashionable “Anthropocene,” which is increasingly used to denote our current geological epoch. In Pyne’s view, the Age of Man can be redefined “according to humanity’s primary ecological signature, which is our ability to manipulate fire.”

From the hearth to the boiler to the rocket engine, fire is what modern human society is built upon, and the excess carbon dioxide from all that combustion has, ironically, made conditions rife for runaway conflagrations, as wildfires now rage—out-of-season and out-of-control—seemingly everywhere, from California to Greenland, the Arctic to the Amazon.

Fire, Pyne wrote when introducing the book on his website, “gave us small guts and big heads, and then took us to the top of the food chain.” Now, it might well be the death of us.

Refreshingly, the author is more pragmatist than moralist when it comes to the current climate crisis. He observes that, paradoxically, man’s early use of fire may have saved us from another ice age. Taking the long view, he argues that it’s now imperative “to keep our fossil biomass in the ground … not only to cool humanity’s feverish presence today but to have it as a stockpile to ward off the ice’s return in the future.”

—Patrick Joseph

New Time: Art and Feminisms in the 21st Century

BAMPFA

In August, the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) opened New Time: Art and Feminisms in the 21st Century. Visitors to the exhibition are greeted by one of Venezuelan American painter Luchita Hurtado’s final commissions—a giant mural with words such as “sky” and “corpse” etched into a landscape-like painting—before entering a series of eight galleries touching on different feminist themes, starting with “Arch of Hysteria” and ending with “The Future Is Feminist.”

The exhibition, which runs through January 30, 2022, comprises more than 140 artworks by 77 different artists, including women, men, trans women, and nonbinary artists. The section “Gender Alchemy” also highlights work that conveys shifting categories of gender, including its namesake, Three States of Gender Alchemy (2015), a ceramic sculpture by Nicki Green, MFA ’18.

A.J. Fox, media relations manager at BAMPFA, calls the extensive survey of feminist paintings, photographs, video, and sculpture the “art world’s version of the Women’s March” and notes that it is part of a yearlong series presented by the Feminist Art Coalition. As one of the first public exhibitions at the museum since the pandemic began, New Time shows the durability of women, the world, and BAMPFA in the face of new challenges.

—Margie Cullen