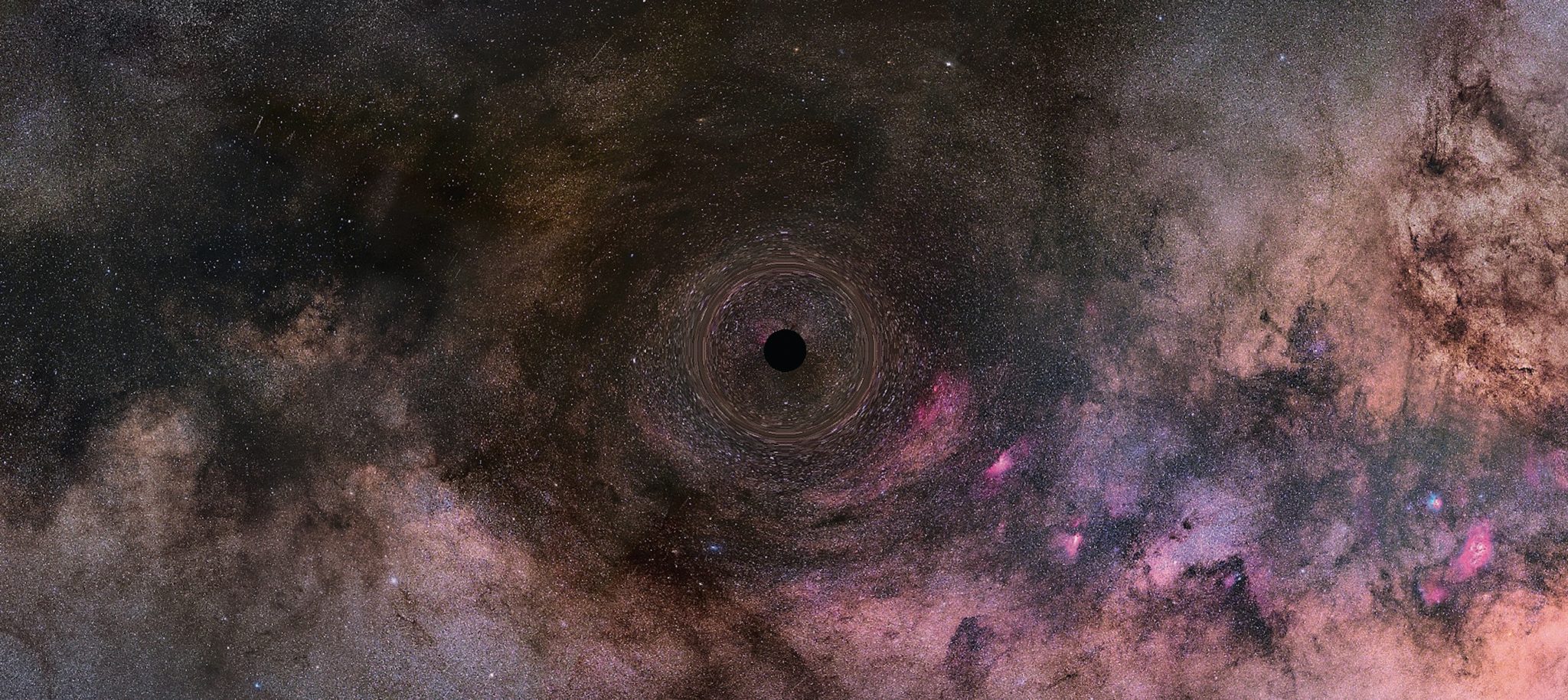

Berkeley astronomers, using the Hubble Space Telescope, have detected what may be the very first “free-floating” black hole ever recorded, about 2,200 to 6,200 light-years from Earth. Dubbed “stellar ghosts,” these black holes are invisible, left behind after a massive star—at least 10 times the mass of the sun—dies and collapses in on itself.

“Every black hole that we found up until this discovery has either had a companion star, another companion black hole, or had gas falling into the black hole,” explained Jessica Lu, associate professor of astronomy. “Something that made it shine, something that caused it to glow in order for us to be able to see it.”

So, how did researchers find something that’s not visible? The Berkeley team, led by graduate student Casey Lam, M.A. ’19, Ph.D. ’23, can thank gravitational microlensing—a phenomenon that occurs when light emitted from stars gets warped or distorted due to the gravitational pull of other massive celestial objects, like black holes.

“When gravitational lensing occurs and the lens is very massive, we can actually see that the background star makes a little horseshoe in its path on the sky. That’s the signal that we’re looking for,” Lu said.

But that’s just the beginning. Once a gravitational lensing event is detected, astronomers still need to determine whether it’s a black hole, a star, or even an exoplanet. “Everything that has mass can produce gravitational lensing signals,” Lu pointed out, which makes it “a little bit like finding a needle in a haystack.”

Two teams, including Lam and Lu’s, have been monitoring this particular event since 2011. Not until now has the competing team, led by Kailash Sahu at the Space Telescope Science Institute, been confident enough to conclude that it is a free-floating black hole, which, just like it sounds, drifts in the cosmos.

Still, some uncertainty remains. Stars that explode in a supernova can also collapse into a neutron star, another highly dense but smaller mass object. The Berkeley team cautions that the possibility that the object is a neutron star can’t be entirely ruled out.

…

California magazine is an editorially independent non-profit magazine. We need your support to keep producing award-winning journalism about the world of Berkeley and Berkeley in the world. Please consider a donation in any amount. Fiat Lux and Go Bears!