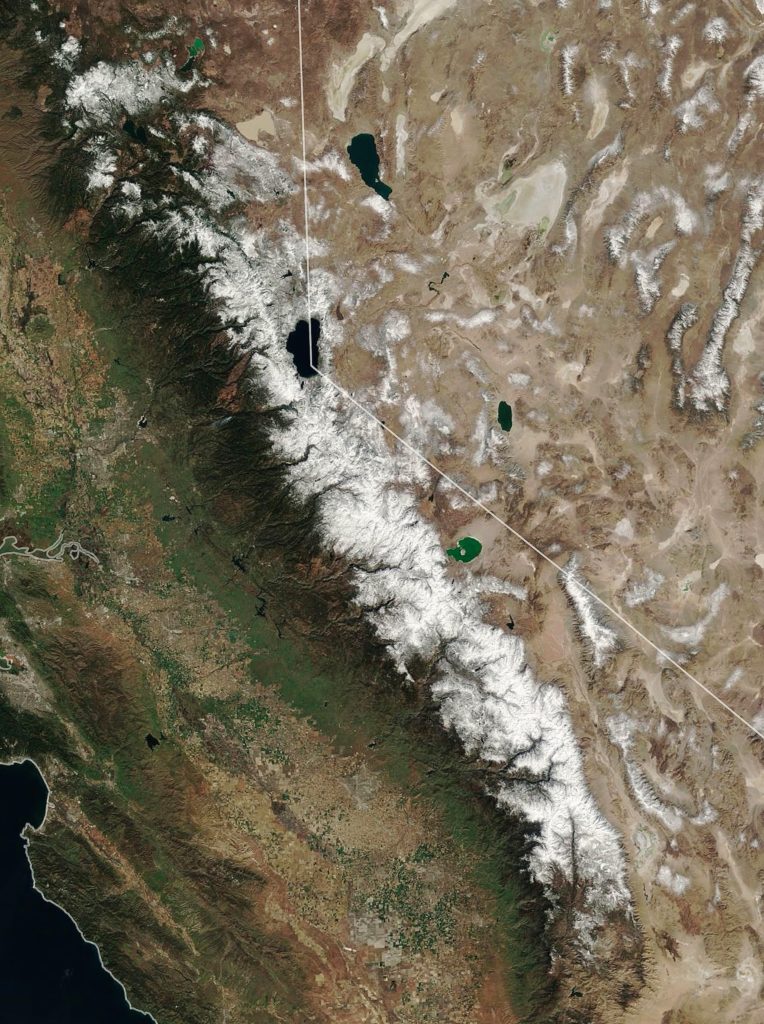

The Sierra Nevada—the “Snowy Range”—is about to get a lot less snowy according to a study co-led by Berkeley Lab researchers. Published in the journal Nature Reviews Earth & Environment in October, the study concludes that certain mountain ranges in California and the western United States could be nearly snowless for years at a time in a matter of decades.

It’s a projection that has significant implications for wildlife, agriculture, and energy in the region—not to mention skiing. In California, the average annual snowpack accounts for 30 percent of the state’s fresh water supply, and water managers have long depended on spring and summer snowmelt to supply water when demand is highest. They may not be able to depend on it much longer.

According to the paper, a synthesis of existing literature on the subject, the Golden State could face five-year periods of low or no snow by the 2040s and ten-year snow droughts by the late 2050s.

Western U.S. snow accumulation has been on the decline for some time, a symptom of climate change. Across the Mountain West, snowpack has diminished by about 20 percent since the 1950s, a loss equal to Lake Mead, the largest reservoir in the United States by volume (which has recently dropped to record low levels). But what happens when our alpine “water towers” vanish completely?

“We don’t have any historical analogues of this persistent snowpack loss,” Berkeley Lab’s Erica Siirila-Woodburn, a lead author of the study, told the Washington Post. “That, hydrologically, is a totally different beast.”

The authors of the study suggest a few “creative and flexible strategies” for adapting to the new regime. Storing water from wet years in underground aquifers would help, as would improved seasonal forecasting to better inform water managers’ decisions about when to hold or release water from reservoirs. Of course, the report itself could help us adapt, if we heed its warnings.

As Berkeley Lab’s Alan Rhoades, another of the paper’s lead authors, told High Country News, “The main point is to try to be proactive about all of this, rather than reactive.”