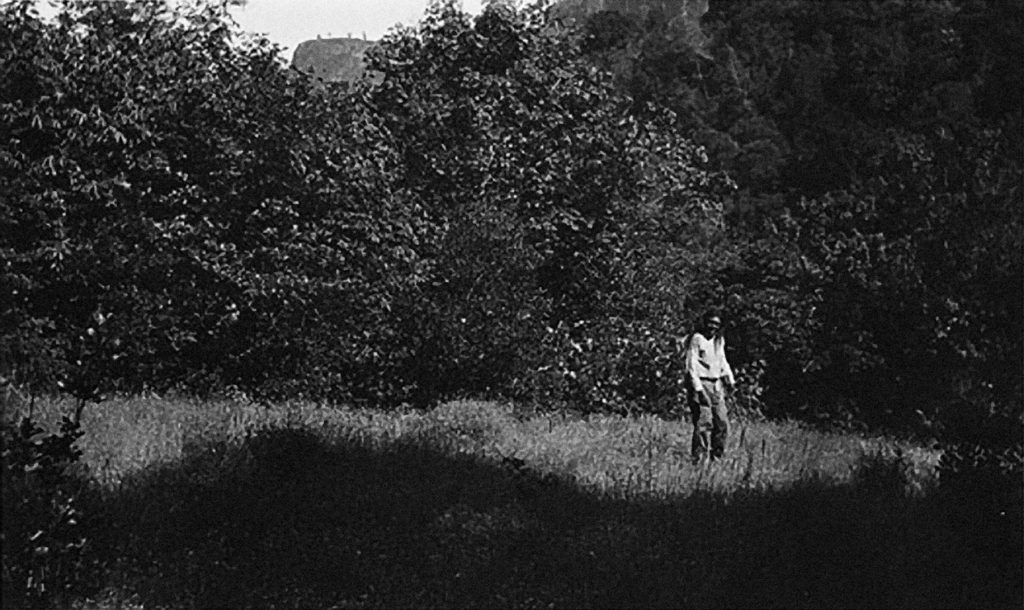

To get to the Ishi Wilderness you’ll want a full tank of gas and four-wheel-drive. Even then, you should be willing to ditch the car and walk. The approximately 41,000-acre wilderness area is located in the Lassen National Forest in a remote part of the southern Cascade foothills northeast of Chico, within sight of Mount Lassen.

My plan was to hike to the Ishi Marker, a monument to California’s so-called “last wild Indian,” and camp in the area near where he and his tribe had wintered. But when I arrived at a gas station along a dirt road entering the wilderness area, the attendant had never heard of the campground where I planned to stay. I told him it was 20 miles down the road we were on. He told me he had never been 20 miles down that road.

I soon learned why not. It’s nearly impossible to drive that stretch. After seven miles of rocky, steep terrain that more closely resembled a hiking trail than a road, I abandoned my car, gave up on the monument, and settled for hoofing it down to Deer Creek.

Ishi looms large in California lore, but prior to moving to the state six years ago, I had never heard of him. It embarrasses me to say this now, but it hadn’t occurred to me that there could have been Native Americans living in the wilderness in the 20th century. Though Ishi had been dead for more than 100 years, he was now at the center of a controversy playing out on the Berkeley campus.

Two years ago, a proposal had been submitted to unname Kroeber Hall, the home of the anthropology department. Its namesake, Alfred Kroeber, was considered the father of West Coast anthropology and is one of the reasons why Berkeley’s anthropology department is considered one of the most outstanding in the country. Being hotly debated was his treatment of Ishi both before and after the Yahi man’s death, as well as designations Kroeber had made about Bay Area tribes, and, ultimately, the very praxis of anthropology itself.

There had been other unnamings on campus in 2020, including the high-profile name of the main classroom wing of Berkeley’s esteemed law school. To many, this one was different. “Kroeber was a really tough one,” said Paul Fine, former chair of the Building Name Review Committee and a Berkeley professor of integrative biology. “[Boalt] was totally easy.”

As Andrew Garrett, a Berkeley professor of linguistics, told me, “One of the really striking aspects of the whole Kroeber Hall business was how loud the accusations of racism and eugenics were, which is a kind of a weird irony, given that in the early 20th century, he was one of the most vociferous, anti-racist and anti-eugenicist academics around.” Kroeber’s work recording Indigenous languages and traditions had been, Garrett explained, “a valuable resource for communities all around California who are trying to reinstate cultural practices and relearn songs and recover vocabulary that’s lost.”

But inherent in Kroeber’s relationship with Ishi, many saw a troubling power dynamic, large blind spots, ethical violations, and, in some instances, willful indifference. While many of those in favor of unnaming were willing to acknowledge Kroeber’s contributions to the record of Native Californians, they also felt he had made some unforgivable mistakes. Caroline Fernald, executive director of the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, explained the pro-unnaming perspective this way: “He may have done 100 million wonderful things, [but] he did this one act, and that can’t be forgotten.… [Kroeber] represents something bigger than what he is.”

Given the complexities, the dense Ishi Wilderness seemed an apt metaphor for the tangled debate. While opponents decried the unnaming as a simple act of cancel culture, it appeared that something more complicated was going on, and the arguments for and against the removal were many layered, thick with multi-generational pain and ideas about what academic scholarship should and should not be. On both sides, there were passionate pleas and a sense of urgency over things that had occurred in the previous century. The story recalled Faulkner’s oft-cited quote: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Standing at the edge of the Ishi Wilderness, I began to think that I might rather not go in. It was almost three in the afternoon. The air was thick with biting flies and mosquitos. If I hiked the seven miles down to Deer Creek, I would be walking back uphill in the dark. As hot as it was then, the temperatures would drop 30 degrees when night set in. Who knew what—or, perhaps more alarmingly, who—I would encounter. I called my editor, half-hoping he would tell me to scrap the whole thing. He didn’t. I packed warm clothes and enough food and water that if I got stuck down there, I wouldn’t starve or freeze, and headed in.

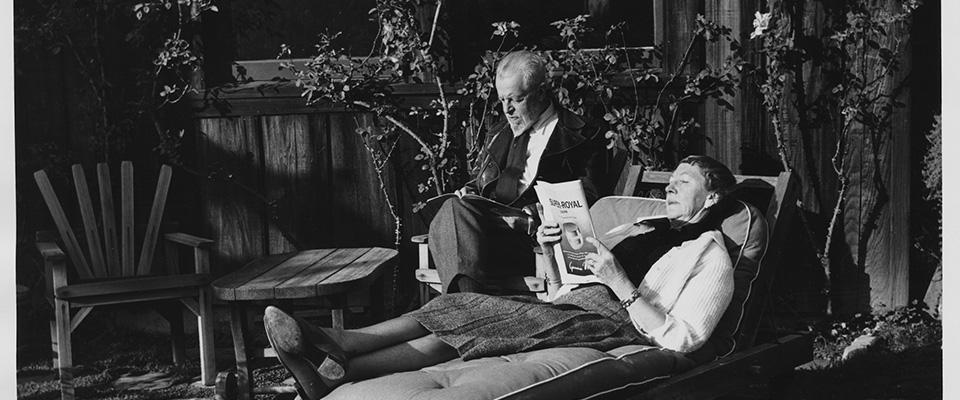

The most widely read book-length account of Ishi’s life comes from Kroeber’s second wife, Theodora Kroeber. Ishi in Two Worlds was first published by the University of California Press in 1961, a year after Alfred’s death, to tremendous acclaim and commercial success, selling more than a million copies. While critics have since pointed out factual errors and convenient omissions in her account, it nevertheless provided a rare, unflinching account of the slaughter of Native Californians by white settlers.

More recently, Duke University cultural anthropologist Orin Starn produced a kind of corrective, lesser-read, but strenuously researched volume titled Ishi’s Brain. While the books differ on many points, they broadly agree on the basic story.

In 1911, the man who would be known as Ishi walked out of the wilderness near Oroville. Starn writes that when he approached a slaughterhouse, the young men who worked there assumed at first that he was a Mexican thief. One of the slaughterhouse workers was about to knock him out with a hog gambrel when he noticed that the man was barefoot and had a small stick piercing his septum. When the workers spoke Spanish to the man, he looked at them uncomprehendingly.

A few years earlier, there had been murmurings about a free tribe living in the foothills near Deer Creek. Could this man be one of them? They called the sheriff, who came, handcuffed the unprotesting stranger, and brought him to the Oroville jail, where he was greeted by a crowd of gawkers.

In the coming days, papers across the country heralded news of “the last wild Indian.” Perhaps no one was more interested than Alfred Kroeber, the young, ambitious founder of Berkeley’s anthropology department. While anthropology at the time was rife with eugenics and white supremacist ideology, Kroeber had studied under Franz Boas, a Jew from Germany, a reformer of the field, who eschewed the idea of inferior races. Kroeber’s intellectual interest lay almost entirely in recording Native Americans’ habits and language prior to their exposure to white culture.

Kroeber sent his colleague T.T. Waterman to locate the man and garner as much information as he could about his tribe, later determined to be the Yana-speaking Yahi people. Over the course of these jailhouse interviews, important details of the man’s life emerged. For a long period, after much of his tribe had been murdered by gold rush settlers in the 1860s, the man led a furtive existence with just four other survivors. A woman, possibly a wife or a cousin, had drowned, and now he was alone. His hair was burned short, a symbol of mourning.

Since the man had committed no crime, the sheriff was eager to get him out of the jailhouse. Kroeber wanted to bring him to Berkeley for further study. The man did not want to go to a reservation, nor did he want to return to a lone existence in the wilderness. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (Native Americans were not considered citizens, but rather wards of the state) consented to releasing him to Kroeber’s care. He was given Western clothes and boarded a train to San Francisco. Kroeber and Waterman decided to house him in what would soon become the university’s anthropology museum.

By custom, he would not share his name with strangers, so when the increasingly inquisitive media pressed for one, Kroeber supplied “Ishi,” an anglicization of the Yana word for “man.”

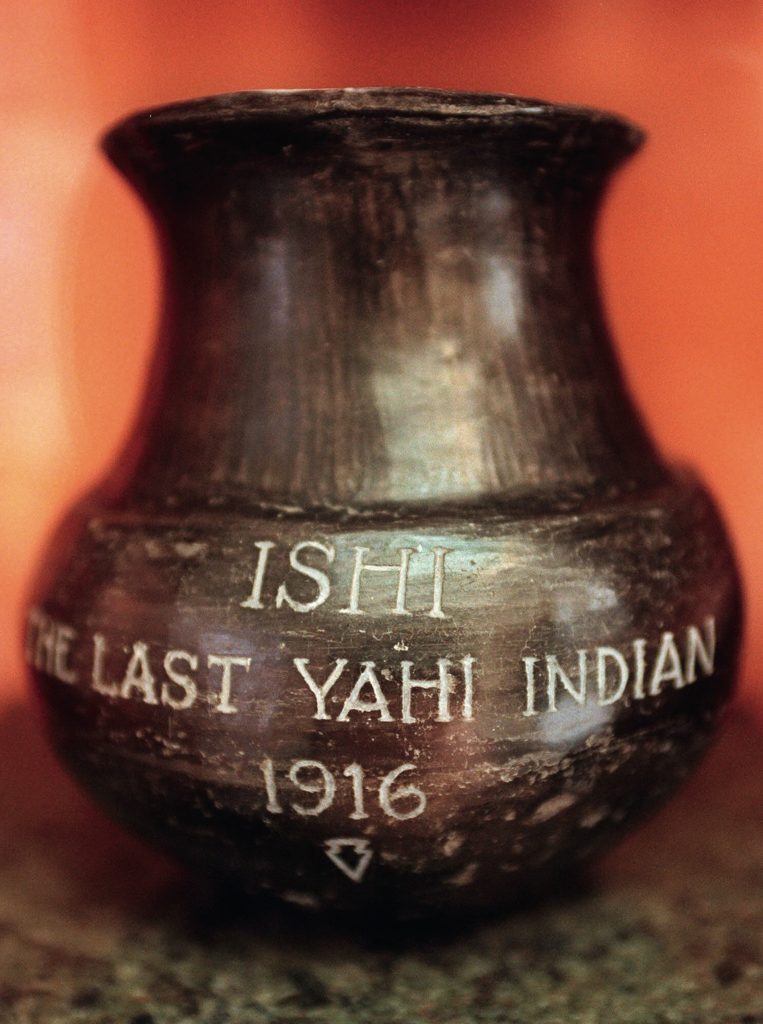

Ishi would live in the museum for the next four and a half years, working as a janitor and research assistant and giving demonstrations of traditional craftwork to enormous crowds. By all accounts, he did this work willingly, and in many cases had warm relations with anthropologists, administrators, and their families. He died in 1916 of tuberculosis, likely the result of exposure to the museum’s vast crowds.

Complaints about Kroeber Hall had been circulating among Native Americans for years, to no effect.

“I think people had kind of given up on the university doing anything,” said Phenocia Bauerle, director of the Native American Student Development office and a member of the Apsáalooke tribe. In 2018, after the chancellor had created the Building Name Review Committee yet “not a single name [had] changed,” the Daily Californian ran an editorial calling for the unnaming of Boalt, Barrows, LeConte, and Kroeber halls, as well as a more efficient, public process to do so. Then, amidst the racial justice reckoning that occurred after George Floyd’s murder, university administrators took proactive steps to redress the past. The Building Name Review Committee began looking at Barrows and LeConte halls, which eventually had their names removed. The executive vice chancellor and provost’s office examined the complaints about Kroeber and began soliciting the advice and signatures of the Native American Advisory Council, academics, and students.

The resulting proposal argued that “Alfred Kroeber was a complex human being who sought to create and share knowledge and was influential in the overall development of his field.” It added that while Kroeber alone was not to blame for the damaged relationship between the university and Native Americans, he was, for many, a “hostile symbol” and concluded that the unnaming was an “important symbolic change.”

There were three main points to the proposal’s argument. The first was that “Kroeber and his colleagues engaged in collection of the remains of Native American ancestors, which has always been morally dubious and is now illegal.” Secondly, that “Kroeber pronounced the Ohlone to be culturally extinct, a declaration that had terrible consequences for these people,” and, finally, that “Kroeber’s treatment of a Native American man we know as Ishi and the handling of his remains was cruel, degrading, and racist.” It ended by saying that the university must acknowledge hard truths, beginning with the unnaming of Kroeber Hall.

The Building Name Review Committee then solicited feedback in the form of online comments.

One in favor of the unnaming alleged, falsely, that Kroeber was “an outspoken white supremacist,” while another claimed, “Destroying history will not solve it. Great men should be measured by the standards of their era, not our modern cancel culture.” Another asked, “Why build anything if your children will tear it down?”

Among the appeals for unnaming was a letter from the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe of the San Francisco Bay Area—whose ancestors had been included in Kroeber’s assessment that the Ohlone were culturally extinct—which argued that the unnaming “would represent a powerful symbol acknowledging the survival, achievements, and continuous existence of the Muwekma Ohlone people.”

Alfred and Theodora Kroeber’s great-grandson, Gavin Kroeber, wrote in favor of the removal, in recognition of “the ways my ancestors’ work proceeded within systems of white supremacy and served to reproduce those systems, even as they made efforts to repudiate racist ideologies.” He went on, “It is not easy to have Alfred Kroeber’s name come down in such bad company—alongside the figureheads and agents of racist ideologies that Boasian anthropology directly opposed and often worked to dismantle.” But, he argued, “I don’t believe there will be a perfect moment, when the optics feel just right and the language attends to everyone’s sensitivities.”

Notable voices opposed to unnaming included Kent Lightfoot, a well-respected Berkeley anthropologist, who argued that “while there are important issues to consider concerning his research practices as perceived in 2020,” the proposal was “overly harsh” and contained inaccuracies. He refuted claims that “Kroeber engaged in research practices that are reprehensible and always objectionable to many Native Americans.” If that were the case, why was Kroeber asked to be an expert witness in Native American tribes’ suit against the U.S. government for reparations for stolen land, a case that resulted in a $29 million settlement to them?

Garrett, the linguistics professor, wrote that “we should rename the building without exaggerating our critique of A.L. Kroeber,” and that “focusing on Kroeber also distracts us from honest self-examination, suggesting that our problem lies with a single villain rather than being what it is—foundational and systemic.” When I followed up with him on his response, he told me that there were two separate issues presented by the unnaming process: “One issue is around what to think about Kroeber,” and the other: “What is the impact for present-day people with a building that has that name on it?” He said the answers to those two questions point to different outcomes, adding, “The campus, I think, did a poor job of acknowledging the difference between those two things.”

One of the main criticisms of Kroeber stems from his treatment of Ishi.

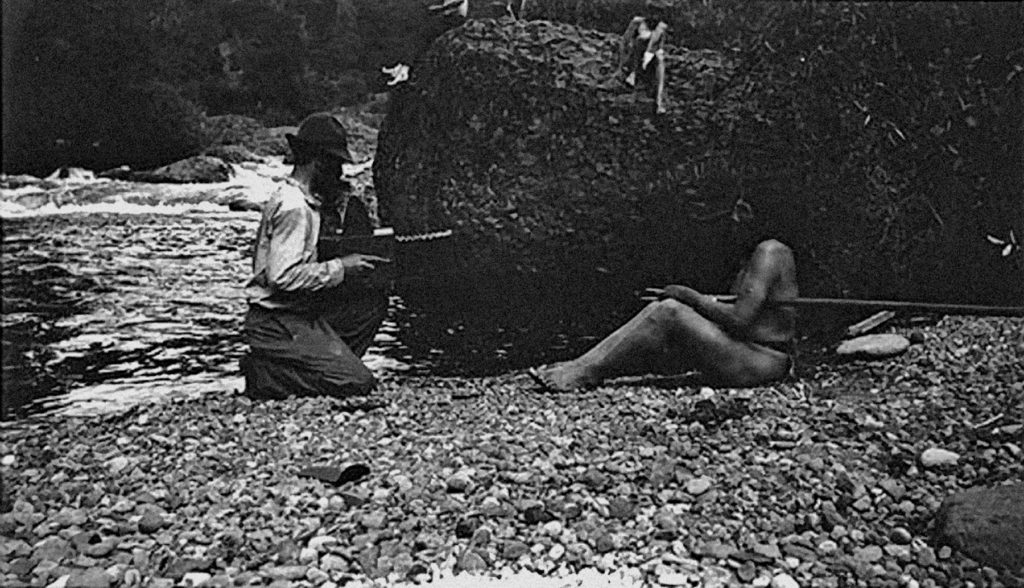

Many accounts describe Ishi, Kroeber, and the other anthropologists as having a warm friendship, and even those critical of Kroeber acknowledge that this was likely the case. Ishi often ate dinner at the Kroeber home, and for three months, he stayed with Waterman’s family. When Ishi died, Waterman wrote to Kroeber, “He was the best friend I had in the world.” Ishi seemed particularly fond of a UC doctor, Saxton Pope, whom he spent a great deal of time practicing archery with.

“He was a living display. I mean, that’s bad. How does that happen?”

Sabrina agarwal

But Fernald, the museum executive director, cautioned against viewing this friendship outside of its power dynamics. Characterizing the relationship as a “friendship,” she said, was “sentimental.” Kroeber made “an extremely disturbing decision to bring a living human to be put on display for the entertainment of others.”

Sabrina Agarwal, a Berkeley professor of anthropology and one of the signatories of an endorsement letter accompanying the proposal, echoed that view. “He was a living display,” she said. “I mean, that’s bad. How does that happen?” At the same time, Agarwal explained that putting living humans on display was not considered unethical at that time, so we shouldn’t villainize Kroeber. “[The unnaming] isn’t saying that he’s a horrible monster. What we’re saying now is that the things that he did hurt constituents on our campus.… It’s not that we’re dishonoring the person, it’s just that times do change … It’s actually honoring the voices of other people on campus.”

“There is rightly much consternation today that Ishi performed public demonstrations,” Lightfoot wrote in his proposal response. However, he argued that “Ishi played a crucial role in helping to create a positive image for Native Californians who continued to face much prejudice and discrimination in the state.”

Perhaps of greatest concern regarding Ishi’s treatment is something that occurred after his death. In all accounts I’ve read, including Theodora Kroeber’s, Ishi was disturbed by the presence of human remains in the museum. To treat the human body this way was a desecration. He made his wish for a traditional Yahi cremation and burial clear.

Kroeber was out of town when Ishi died in the museum in 1916. When he learned that Ishi’s beloved friend Saxton Pope wanted to do an autopsy, he wrote an urgent message to Edward Gifford, the museum’s assistant curator: “Please shut down on it.… If there is any talk about the interests of science, say for me that science can go to hell. We propose to stand by our friends.”

While that detail is in Theodora Kroeber’s book, she seems to have conveniently left out what happened next. The autopsy was performed, and while the rest of Ishi’s body was eventually cremated and buried, his brain had been removed and preserved. For reasons that are not clear, Kroeber had reversed course and arranged for the brain to be sent to the Smithsonian. Every response I read, including those that opposed the unnaming, lamented this decision. It was a violation, Kroeber knew, and he did it anyway. It would be almost a century before Ishi’s brain was recovered from the Smithsonian and repatriated to the Pit River Tribe and buried in a secret location in the Ishi Wilderness.

Another continual sticking point in Kroeber’s legacy is his relation to the Ohlone who inhabited the land where the Berkeley campus now sits. In 1925, Kroeber evaluated them as being culturally “extinct,” a distinction that some argue cost the Ohlone federal recognition, which they still lack. “This is a big source of pain,” said Agarwal. Alexii Sigona, a doctoral student at Berkeley in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management, explained that as a member of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band representing the Mutsun-speaking Ohlone people, the unnaming of Kroeber Hall “is definitely a really personal issue for me.”

While Sigona uses Kroeber’s book, Handbook of the Indians of California, to better understand his tribe’s traditional practices, he points to the irony in crediting Kroeber with “preserving” their culture. “Why do I have to go back to these books to learn about my culture sometimes? Why do these things become dormant? Well, that can be answered by land dispossession.”

Garrett argues that the question of the Ohlone’s federal recognition is not so simple, however. He says it’s not clear that L.A. Dorrington, the Bureau of Indian Affairs official who determined which “bands” needed land bought for them, based his decisions on Kroeber’s assessment. “There is no evidence that Dorrington read Kroeber,” Garrett wrote. “[I]n fact, he recommended purchases of land for some groups that Kroeber had called ‘extinct’ and overall he did not recommend very many land purchases anywhere, even for non-‘extinct’ groups.”

Regardless of whether Kroeber was directly responsible for the Ohlone’s dispossession, Sigona and some contemporary anthropologists take issue with Kroeber’s approach to the discipline, often referred to as salvage anthropology, which treated Indigenous peoples as a vanishing race and relegated their cultures to the past.

Says Agarwal, “They didn’t need to have the white man preserve their culture for them and tell them what’s real and what’s not real.”

Perhaps no other issue around this topic is quite as contentious as the fact that Berkeley continues to hold Native American remains in its collection. Patrick Naranjo, the executive director of the American Indian Graduate Program, a signatory of the letter endorsing the unnaming proposal, and a member of the Santa Clara Pueblo, put it this way: “We’re talking about people studying people, and then collecting them, and then having trouble returning them.” Agarwal echoed the complaint: “We have layers of structural violence here. We have displacement, we have genocide, we have the forced migration of people. We kill them, and then we take their dead, and keep them in a museum. And then we don’t give them back when they ask…. This is all equated with Kroeber.”

In his response to the proposal, Lightfoot argued that there was no evidence that Kroeber himself collected remains in California, as was common for archaeologists at the time.

The practice is now illegal in the United States, and nearly everyone I spoke to cited it as one of the greatest sources of continued pain for Native Americans. Repatriation of remains was at the top of their list of substantive measures the university could take to repair its relationship with the tribes.

In January 2021, after the Building Name Review Committee made its recommendation, Kroeber’s name was quietly removed, letter by letter. It was a symbolic gesture and, by some measures, an empty one. As Fine, the former committee chair, said, “Just removing the name alone and not doing anything else is kind of insulting in a way, right?” The committee issued a memo that called for a wider, proactive examination of the university’s role in racism and discrimination, as well as for a working group to consider the creation of exhibits, murals, and programs; new faculty and staff hires; and the return of lands to Bay Area and California tribes.

“Just removing the name alone and not doing anything else is kind of insulting in a way, right?”

Paul Fine

The university has already taken steps toward repatriating human remains. “[T]his university—this museum specifically—has a legacy of being resistant to repatriation,” said Fernald. Now that appears to have changed. “We’ve prioritized repatriation above everything else,” she said, which means that the museum has suspended class visits, exhibitions, research appointments, and any of the operations that support the campus in order to focus on this effort. While bureaucratic hurdles remain and the process is slow, she insists “the goal is 100 percent repatriation.”

She said they also hope to return to appropriate tribes all of Ishi’s objects, including the clothes he was wearing when he arrived, the craftwork he did on campus, and his death mask. There have also been conversations about creating a repatriation exhibit to help educate the public.

In a surprising turn of events, Cafe Ohlone, a restaurant featuring Ohlone cuisine, will now take up residence at the museum, a suggestion put forth by Lightfoot. Where once the Ohlone felt erased by Kroeber, they now have space at the hall that used to bear his name. “The Cafe Ohlone project is a really an exciting opportunity to build and repair relationships with Native communities and to have the site of Hearst museum be a site for healing and a site for reparation,” Fernald said.

Bauerle, of the Native American Student Development office and another signatory of the letter accompanying the unnaming proposal, also cited new hires on campus as real progress. “Until two years ago, there were three Native faculty on campus, and two of them taught in Native American studies. So there really wasn’t diversity across campus in terms of representation or even the types of classes that could be taught.” She also mentioned a plan for UC-wide scholarships aimed at bringing more Native students to campus.

For now, all of the Native American students and administrators I spoke to were cautiously optimistic about these developments. “I’m very interested to see what will happen with repatriation,” Sigona said. “Of course, it’s good to be skeptical a little bit, but it seems like there is a new chapter in the repatriation policies.”

It was dark when I got back to my car, but I was glad to have gone in, even if the experience hadn’t been what I had hoped for. While the wilderness was rugged and expansive, there were troubling signs of encroachments. I had seen a few abandoned and looted cars on the side of the trail, and someone seemed to be living by Deer Creek, as evidenced by a makeshift tent and a set of tools, including large shears. A truss bridge now crosses Deer Creek, and it’s covered in graffiti, including racial slurs.

At the same time, from certain vantage points, the area is gorgeous and otherworldly, with strange lava formations protruding upward like massive pillars. You can stand on an outcropping overlooking the vast ridges and rocky canyon below and briefly have the impression that you are the last person on Earth.

I tried to imagine what it had been like when Ishi was alone in these woods, hearing the sound of a steam train whistle in the distance. He knew that there were white people out there, that an encounter with them would likely be fatal. He was, by most accounts, a survivor of their massacres. But now he was starving and aging. He could choose between laying down and dying or walking toward the unknown sound. To walk out of the wilderness, out of the only world you’ve ever known—it’s hard to imagine a greater leap.

“Ishi will always be associated with the Hearst museum. Whether or not it’s a positive legacy, it’s part of our legacy.”

caroline fernald

During the time that Ishi lived in Berkeley’s museum, he was known to say in parting, “You stay, I go.” But in a poetic reversal, Ishi’s mark on the university has outlasted almost everyone else who came and went. “Ishi will always be associated with the Hearst museum,” said Fernald. “That’s part of our legacy. Whether or not it’s a positive legacy, it’s part of our legacy.”

I had been thinking a lot about legacy. It occurred to me that the unnaming isn’t really about Ishi or Kroeber. It’s about us, the living. To the Ohlone, removing Kroeber’s name is an assertion of their existence. The white man who said they were culturally extinct was wrong. They’re still here, and now they have a say in the story. For the people upset by the removal of Kroeber’s name, they’re grappling with the strong likelihood that one day, the things we do now will be considered reprehensible. Despite our best intentions, our life’s work could be viewed unfavorably—if it’s remembered at all. And we won’t be here to defend ourselves.

When I asked Garrett if we should even bother memorializing people by naming buildings after them, he joked, “Sometimes I think [the names] should change every 20 years.” The suggestion was beginning to sound reasonable.

While some feel that removing Kroeber’s name was an attempt to erase history, the opposite appeared to be true. History had been unearthed, discussed, contended with. More people than ever had been talking about Ishi and Kroeber, and there was some good coming from that. Naranjo, executive director of the American Indian Graduate Program, said that the process forced us to answer the question, “How do we make good anthropologists at places like Berkeley that can further inform the field?”

For his part, Sigona says he wants to balance the historical discussion with “trying to envision what a good future looks like that is sustainable, that really highlights our resiliency. And we know that we’ll be here for many more generations to come.”

Laura Smith is the executive editor of California magazine, co-host of the Edge podcast, and the author of The Art of Vanishing.