1

PCR

By now, most of us have had at least one PCR test for COVID-19, and probably a lot more. The acronym stands for polymerase chain reaction, a quasi-magical lab technique that enables scientists to exponentially amplify bits of DNA for study. A truly transformational technology, PCR gets used for all kinds of things, from diagnostics to forensics.

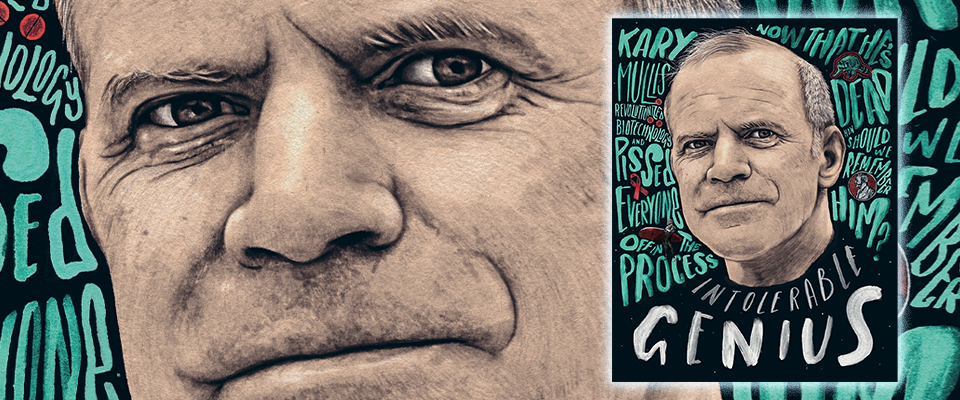

The revolutionary process was first devised by Berkeley alumnus Kary Mullis, Ph.D. ’73. The iconoclastic biochemist was working at biotech pioneer Cetus when he had his eureka moment. By his own account, he was driving his Honda Civic north on Highway 128 one day in 1983 when it hit him.

He wrote in his autobiography, Dancing Naked in the Mind Field, that he knew immediately that “everybody on Earth who cared about DNA would want to use it. It would spread into every biology lab in the world. I would be famous. I would get the Nobel prize.”

And he did, in 1993.

CFCs: In 1995, Mario Molina, Ph.D. ’72, became Mexico’s first Nobel laureate in science when he shared the prize in chemistry with two other UC scientists—F. Sherwood Rowland of Irvine and Paul Crutzen of San Diego—for their work on the hole in the ozone layer, which Molina and Rowland discovered was being caused by a class of chemicals called chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs. The discovery had important implications for life on Earth. As Rowland once told his wife about the work, “Well, it’s going very well—except it looks like it might be the end of the world.” Thanks to their research and the subsequently adopted Montreal Protocol, apocalypse was averted. The ozone layer is on the mend.

2

Wetsuits

In 1943, physicist Hugh Bradner was recruited by the Manhattan Project to develop detonators for the Bomb. After the war, he studied high-energy physics at Lawrence Berkeley Lab and taught physics at Cal. Today, he is chiefly remembered as the father of the wetsuit, an invention he developed for the U.S. Navy and began tinkering with in the basement of his Berkeley home on Scenic Avenue.

The basic problem to be solved was this: The thermal conductivity of water is 25 times greater than that of air. How could divers be protected from hypothermia but still allowed enough freedom of movement to swim?

Rather than keeping divers dry, as previous diving suits had, Bradner’s permeable suits let the water in. First developed in 1952, his “wetsuits” fit like a second skin, and water trapped by the insulating neoprene quickly warms to body temperature.

While Bradner was focused on diving, his invention also revolutionized another sport. As surf historian Matt Warshaw ’92 told the Washington Post, “The wetsuit itself got many more people in the water than any surfboard design in history. You can’t surf if you’re purple and shivering.”

Bradner never patented his invention and never profited from it.

Diving Deeper: In the 1920s, Berkeley chemist Joel Hildebrand created a mix of helium and oxygen that, used for respiration by deep sea divers, avoided the condition known as “the bends,” enabling them to descend to greater depths than ever before.

3

Battle of the Sexes

In 1933, 40 years before 55-year-old Bobby Riggs played and lost to 29-year-old Billie Jean King in a highly publicized tennis match billed as the “Battle of the Sexes,” Cal’s Helen Wills ’27, the greatest female tennis player of her era, defeated 32-year-old Phil Neer, a former NCAA champion from Stanford who was ranked eighth in the country at the time. Wills, then the reigning Wimbledon champion, was only four years Neer’s junior. A few years earlier, in 1928, she also won a set against former Wimbledon champ Bill Johnston. The feats are not well remembered but should be. Even the Williams sisters, Serena and Venus, couldn’t quite match it, having both lost a challenge set to 203rd ranked male player Karsten Braasch in 1998.

Wills, whose success built on that of fellow Berkeley alumna and occasional doubles partner Hazel Hotchkiss Wightman ’11, was once one of the most famous female athletes in the world. Her face graced the cover of Time magazine not once, but twice, and her bust resides in the National Portrait Gallery.

The Long Bomb: No one thought it was possible, least of all the Ohio State defense, but in the 1921 Rose Bowl, Cal’s Harold “Brick” Muller ’24 showed that the long forward pass was not only feasible, but deadly effective. The 6-foot-tall, 180-pound Muller, known for his red hair and huge hands, hucked the pigskin—bigger and rounder than it is today—some 53 yards to teammate Brodie Stephens ’22, who was undefended and walked into the end zone. That made it 14–0 Bears, en route to 28–0 victory. Muller was named the game’s MVP, and his pass made headlines across the country. The news even ran in Ripley’s Believe It or Not, which put the distance at an unbelievable 70 yards.

4

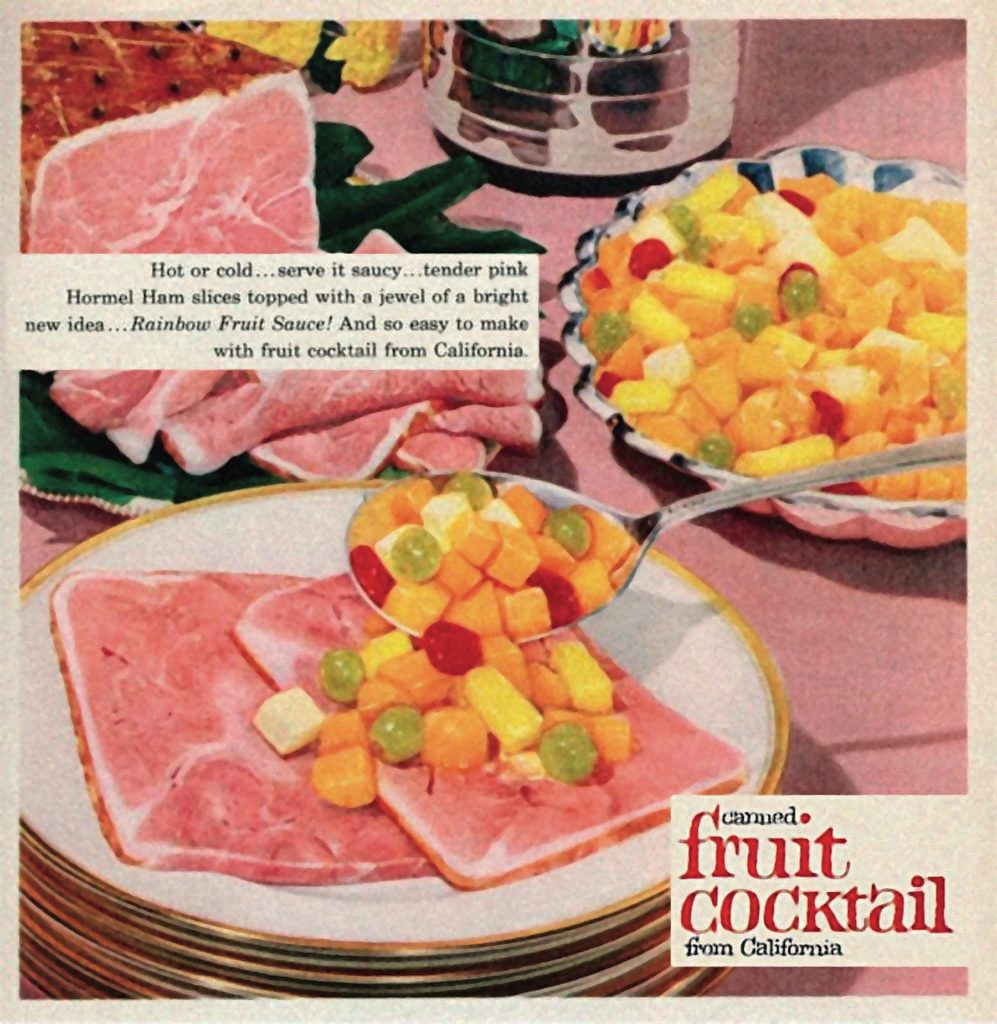

Fruit Cocktail

You think Berkeley and you think California cuisine. You think Alice Waters and fresh, organic farm-to-table fare. You don’t think of fruit salad vacuum-packed in syrup with maraschino cherries. But think again. Even the old Del Monte lunch-bucket standby can trace its roots to Cal, specifically in the figure of food science pioneer William Cruess.

In addition to inventing fruit cocktail, Cruess, who graduated from Cal in 1911 and taught at his alma mater for decades, is credited with helping develop raisin cereals, raisin bread, prune juice, apricot nectar, and concentrated fruit juices. To scan the titles of his books and circulars is to imagine his signature on everything from Fig Newtons to Pop-Tarts.

But before you gourmands write him off as a throwback to the bad old days of processed foods, here’s something to consider: Cruess’s work was also instrumental in rekindling the California wine industry after Prohibition.

Brewpubs: The man who made the brewpub revolution possible was former Berkeley mayor and Cal alum Tom Bates ’61, who, as a state assemblyman, wrote Assembly Bill 3610, which was passed into law in 1982. The legislation allowed brewers to serve their product directly to customers as long as food was also served. Love you some craft beer? Raise your next pint to Tom.

5

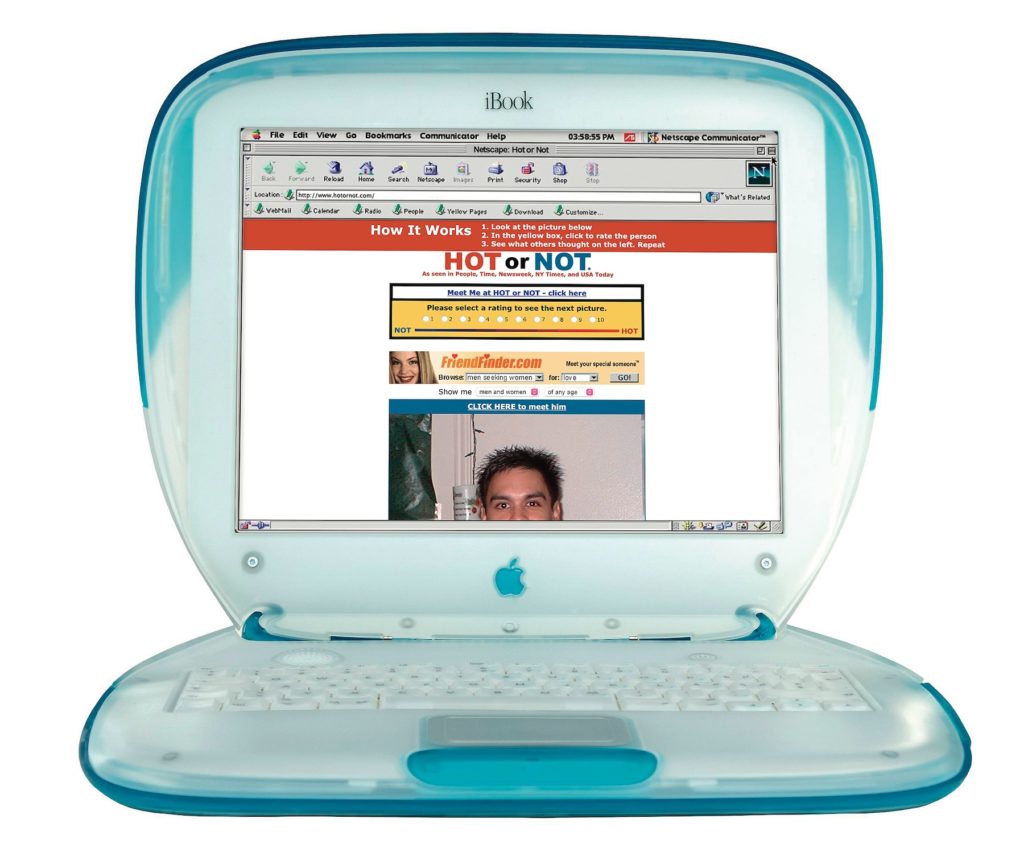

Hot or Not

Before there were iPhones or Facebook or Tinder, there was HOTorNOT, a website where you could post a picture of yourself and ask to be rated for attractiveness. The site, created by Berkeley students James Hong ’95, MBA ’99, and Jim Young ’94, M.S. ’97, Ph.D. ’04, debuted in 2000 and was an immediate sensation, garnering almost 2 million views in a week. That popularity posed a big problem, however, as bandwidth was limited and expensive back then. The duo considered shutting down the site before deciding to surreptitiously run it off UC Berkeley’s networks instead. The extra traffic did not go undetected, and Young was soon summoned by the dean of engineering. Rather than expel Young, who was still working on his Ph.D. at the time, the dean gave him time to find another solution.

While HOTorNOT may seem hopelessly shallow, its influence has been profound, reportedly inspiring the founders of You‑Tube and Mark Zuckerberg, whose first iteration of Facebook—called FaceMash—was basically HOTorNOT for Harvard students.

Apple: Everyone who knows Apple Computer knows the legend of cofounder Steve Jobs, “but what about the other Steve behind the Macintosh? While Jobs was the marketing genius with the exquisite design sense, Steve Wozniak ’86 was the guy in the guts of the machine—the one who made it work. Woz left Berkeley in 1972 to help build the company, but returned a decade later to complete his degree, registering as Rocky Racoon Clark.

6

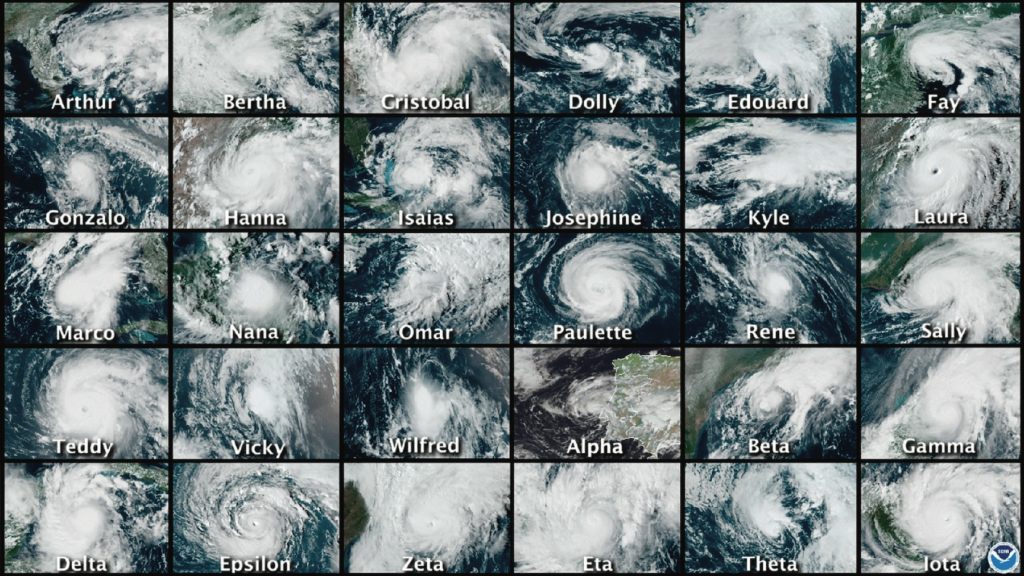

Named Hurricanes

To this day, the hurricane that struck Galveston, Texas, on September 8, 1900, rates as the country’s deadliest natural disaster. It is remembered variously as the Great Galveston Storm, the Galveston Flood, and, simply, the 1900 Storm. Today, it would be given a single proper name, like Elsa or Larry, even before it made landfall.

The practice of christening tropical storms began in 1953, 12 years after Berkeley English professor and popular author George R. Stewart, M.A. 1920, published his bestselling novel Storm, about a Pacific cyclone that brings blizzard conditions to the Sierra Nevada. In the story, a junior meteorologist in the San Francisco headquarters of the Weather Bureau (now the National Weather Service) dubs the weather system Maria.

Naming storms has the obvious benefit of making communications easier, and the idea caught on. Now, with the global thermostat ratcheting up, some want to extend the practice to heat waves. As for the name Maria, it was retired by the World Meteorological Organization after the particularly devastating hurricane by that name struck Puerto Rico in 2017. Other retired names include Katrina, Sandy, and Harvey.

Wind Cries Who? George R. Stewart said his fictional storm’s name was to be pronounced Ma-Rye-Ah, which helps explain how they sang “They Called the Wind Maria” in the 1969 western Paint Your Wagon. Did Storm also inspire Jimi Hendrix’s “The Wind Cries Mary”? Not according to any sources we can find. But get this: Hendrix was inspired by Stewart’s novel Earth Abides to write “Third Stone from the Sun.”

7

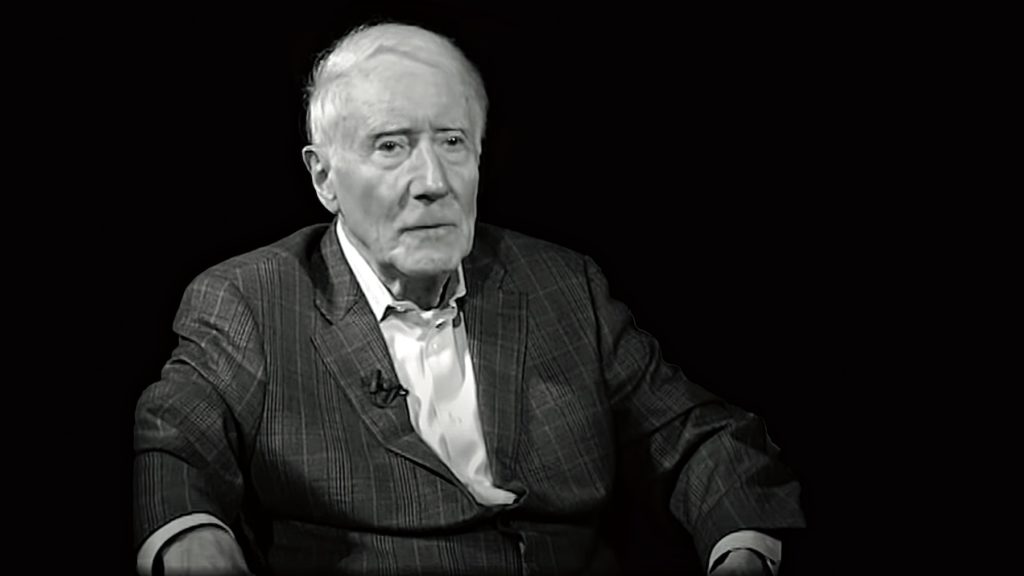

Deep State

On the witness stand at his civil trial in September, InfoWars broadcaster Alex Jones told jurors “I think this is a deep state situation” with respect to the cases brought against him by the parents whose children were slaughtered in the Sandy Hook school shooting. Jones, who repeatedly claimed that the massacre was faked, was invoking a popular conspiracy theory on the far right these days.

As late Berkeley linguistics professor Geoff Nunberg explained on NPR in 2018, deep state is “an elastic label—depending on the occasion, it can encompass the Justice Department, the intelligence communities, the FISA courts, the Democrats, and the media. In short, it’s a cabal of unelected leftist officials lodged deep in the government who are conspiring to thwart the administration’s policies, discredit its supporters, and ultimately even overturn Trump’s election.”

Until then, Nunberg noted, the term had been mostly used with respect to countries like Turkey and Pakistan. Mostly, but not entirely.

In fact, the term deep state was first introduced to and popularized in the American lexicon by Berkeley English Professor Emeritus Peter Dale Scott, a poet, political analyst, and former Canadian diplomat whose many books include: The American Deep State: Big Money, Big Oil, and the Struggle for U.S. Democracy; Deep Politics and the Death of JFK; and The Road to 9/11: Wealth, Empire, and the Future of America. While Scott is very much on the political left, he was an occasional guest on InfoWars, where he and Jones discussed the sinister workings of the deep state.

Scott later said he regretted those appearances. He told a journalist, “They vulgarized the term.”

Radical Right: Berkeley has a well-earned liberal, even radical leftist, reputation, but Cal also has several famous alumni with connections to the far right. Take, for example, shock jock Michael Savage (real name Michael Weiner), who earned a Ph.D. at Berkeley in 1978—in ethnobotany. There’s also David Horowitz, the former communist turned archconservative who graduated from Cal with his master’s in 1961. And going way back, there’s Rousas John Rushdoony ’38, C.Sing. ’39, M.A. ’40, father of Christian Dominionism. Heck, even Fox’s Tucker Carlson is connected to Berkeley—through his mother. Lisa McNear Lombardi studied architecture at Cal. Widely described as a free-spirited artist, she reportedly left the family to pursue a bohemian lifestyle while Tucker and his brother stayed with their dad.

8

The Lie Detector

Put this one in the dubious distinction category. After all, even its inventor, Berkeley Ph.D. John Larson, came to denounce his creation as “a Frankenstein’s monster.” But the lie detector was originally created with the best of intentions, as a way to eliminate the brutal third-degree interrogations administered by cops determined to extract confessions from suspects, guilty or otherwise.

As with many inventions, the claim of whose was actually first is contested. Some say William Moulton Marston, the man who created Wonder Woman, was first to devise the polygraph. Whatever the truth, Larson created his version, the cardio-pneumo-psychograph, in 1920, while earning his doctorate at the university and working part-time as an officer in the Berkeley Police Department.

While Larson grew disenchanted with the machine, his sidekick and fellow Berkeley student, Leonarde Keeler, patented and promoted the machine, ultimately becoming the first professional consultant in its usage.

Police Work: Berkeley’s first police chief, August Vollmer, didn’t have a high school education, but he wanted his cops to have college degrees. Today, he is often called the “father of modern policing.” Among his innovations, Vollmer was the first to implement call boxes, centralized record keeping, and radio-equipped squad cars. He also persuaded the University of California to teach criminology. Perhaps not surprisingly, Vollmer’s legacy has lately been reassessed. Critics say he was a eugenicist who militarized the police force. Defenders, however, point out that he hired Black and female police officers, believed in leniency toward drug offenders, opposed the use of the National Guard to control riots, and discouraged his officers from using their guns.

9

Bullwinkle

One of the first shows that childhood friends and fellow Berkeleyans Jay Ward ’41 and Alex Anderson pitched to studios was called The Frostbite Falls Revue. It featured animated characters Rocket J. Squirrel, the Canadian Moose, and Oski the Bear. While that show never made it to production and the Oski fellow fell by the wayside, the squirrel and moose were revived to become the stars of The Rocky and Bullwinkle Show, which entertained generations of kids with a mix of crude animation and wry humor. The creators weren’t the only Berkeley connection; it seems the white-gloved moose took his name from a Berkeley car dealership, Bullwinkel Motors.

Rube: No one captured the absurdities of the Machine Age quite like cartoonist Rube Goldberg, graduate in engineering, Class of 1904, whose namesake contraptions required all manner of convoluted concatenations and ludicrous linkages just to accomplish the commonplace.

10

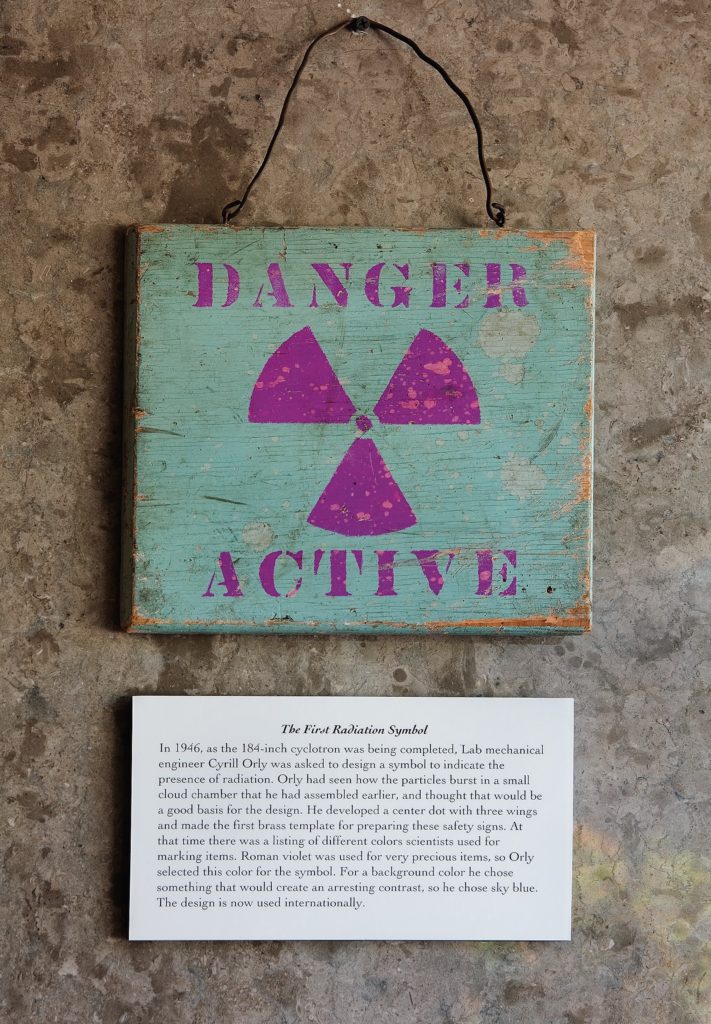

Radioactive Warning Symbol

Of course, you know all about E. O. Lawrence’s cyclotron. You know the story of Oppenheimer and the Bomb, and all about the transuranic elements discovered at the Rad Lab: your californium, your berkelium, your seaborgium, etcetera. But did you know that the radioactive warning symbol—the distinctive black trefoil pattern on the yellow background—also came out of Berkeley?

The symbol was drawn up in 1946 by scientists at the Lab. As Berkeley chemist Nels Garden, M.S. ’32, would later recall, “A number of people in the group took an interest in suggesting different motifs, and the one arousing the most interest was a design which was supposed to represent activity radiating from an atom.” The original color scheme was magenta on blue.

At least one source has suggested that the warning symbol was influenced by a similar sign on a dry dock near Berkeley that warned of spinning propeller blades. Whatever inspired it, the Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity declared it a good choice. “It is simple, readily identifiable (i.e., not similar to other warning symbols), and discernible at a large distance.”

Conservation Measure: Just as the watt (named for inventor James Watt) is a unit of energy spent, a Rosenfeld (named for Berkeley particle physicist and energy expert Art Rosenfeld) is a unit of energy saved. One Rosenfeld equals energy savings of 3-billion kilowatt hours per year, or roughly the annual generation of a 500-megawatt coal-fired power plant. Want to try using it in a sentence? Here goes: If we’re going to beat climate change, we’re going to need a lot more Rosenfelds.

11

Ecstasy

Most people probably know that Timothy Leary was a Berkeley guy. The pied piper of LSD got his Ph.D. at Cal in 1950. Far fewer know about Alexander Shulgin, the so-called “godfather of psychedelics.”

Known to friends as Sasha, Shulgin earned his bachelor’s from Berkeley in 1949 and his doctorate in 1955 and went on to work at Dow Chemical. It was there that he had his first psychedelic experience, with mescaline. It was revelatory. “I understood that our entire universe is contained in the mind and the spirit,” he would say of the experience. “We may choose not to find access to it, we may even deny its existence, but it is indeed there inside us, and there are chemicals that can catalyze its availability.”

Shulgin devoted himself to identifying, synthesizing, and experimenting with hundreds of psychoactive chemicals in his home laboratory. Most notably, in the late 1970s, he resynthesized MDMA and introduced it to psychotherapy. Today, the compound is better known in its street forms as Ecstasy, or X, for the euphoria it induces. While currently a Schedule I controlled substance in the United States, MDMA is being explored as a potential treatment for conditions including depression, addiction, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Purple Haze: To the Grateful Dead, he was Bear. To Steely Dan, he was Kid Charlemagne. To the authorities, he was a menace. Like other famous Berkeleyans (writers Jack London, Philip K. Dick, and climber Alex Honnold come to mind), Owsley Stanley dropped out of Cal after a semester, then turned to cooking up batches of famously pure LSD from

a rented house near campus. His stuff reportedly inspired the Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour, fueled the Merry Pranksters’ Acid Tests, and inspired Jimi Hendrix (him again) to write “Purple Haze.”

Pat Joseph is the editor in chief of California magazine.