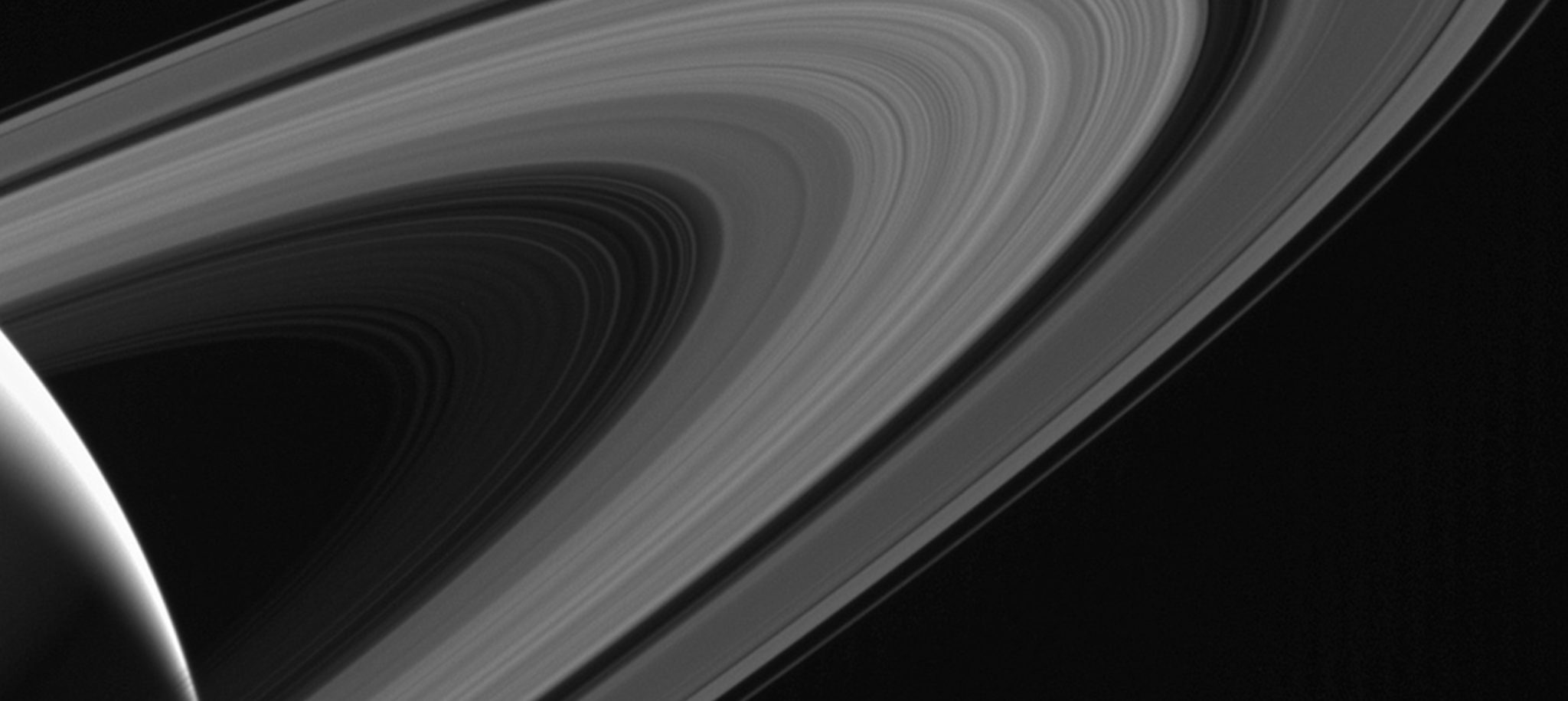

In middle school science class, the planets were all reduced to their most obvious characteristic. Mercury is the smallest planet, Jupiter the biggest. Uranus is the funny one. And Saturn is the one with rings.

Only, it turns out, it didn’t always have them.

While Saturn itself is 4.6 billion years old, the rings are much younger—somewhere between 100 and 200 million years old. Scientists have long wondered, what caused them to form, and why so recently?

Now, a team of astronomers including Berkeley Professor Burkhard Militzer think they have the answer. In a paper published in September in the journal Science, they pin the rings’ creation on a long-lost moon that was torn apart after grazing the planet. They dubbed the missing moon Chrysalis, because it “blossomed” into rings like a chrysalis transforms into a butterfly.

Chrysalis didn’t transmogrify without help. The researchers believe that another of Saturn’s 83 existing moons, Titan, caused it to veer out of orbit.

Titan is currently migrating outward from Saturn at about 11 centimeters per year. Projecting backwards, researchers calculated that, between 100 and 200 million years ago, it would have come close enough to Chrysalis to destabilize it and cause it to drift toward Saturn, where it would be nearly obliterated by the planet’s gravitational force. While 99 percent of the shattered moon probably got swallowed by Saturn, the other 1 percent formed its magnificent rings.

The researchers also suggest that the loss of Chrysalis explains Saturn’s axial tilt, which was long thought to be tied to Neptune’s orbit in what astronomers call spin-orbit resonance. But, as Militzer explains on his website, his team theorizes that Chrysalis gave Neptune an extra “handle” by which it pulled Saturn to its current tilt angle. When that handle disappeared, the two planets fell out of resonance, and Saturn was left spinning at its present angle of 27 degrees.

“It’s a pretty good story, but like any other result, it will have to be examined by others,” said MIT’s Jack Wisdom, lead author of the study, in a news release.

In the meantime, Militzer recommends that next time you peer at Saturn’s rings, “you appreciate them a little bit more because they will not be there forever.” The rings are slowly eroding away, he explains, as particles—leftover bits of Chrysalis—fall into Saturn.