Cal wants to be both elite and equitable. It’s proving difficult.

When Senatorial candidate Barack Obama entered the national stage in 2004 with a speech that passionately advocated for an end to the political thin-slicing of the American identity—red states, blue states, soccer moms, NASCAR dads, yuppies, buppies, bobos, and the like—a new term entered the lexicon: post-racial. Both in his message of hope and change and in the very fact of his campaign, Obama gave wings to the notion that race and ethnicity had ceased to be barriers to opportunity. It was something that people very much wanted to hear.

And with the debate about whether America has finally turned the corner into a post-racial era came new rumblings about affirmative action. Hiring and admissions programs that give advantages to certain “underrepresented minorities”—code for African-American, Chicano/Latino, and Native-American job or college candidates—don’t make much sense when the playing field has been leveled. Class, in this formulation, trumps race. Obama himself announced that he didn’t want his daughters to get preferential treatment in college admissions over “a poor white kid who struggled more.”

But the lingering problem of diversity in higher education casts a pall over all this hope and change. Numerous gaps stubbornly remain—achievement gaps, testing gaps, admission gaps, enrollment gaps, and graduation gaps—for the aforementioned underrepresented minority groups. Over the past 50 years, as the industrial age has given way to the technological one, higher education has become the base for economic and social capital. It matters, greatly, that these gaps have not been bridged.

It is additionally discouraging that these gaps remain at Berkeley, a school with an uncommon commitment to its public mission. Berkeley can take justifiable pride, as Chancellor Robert Birgeneau pointed out in a July note, that over one-third of the undergraduate student body come from families with incomes under $45,000, and 30 percent are first-generation college students. In the face of the decades-old national trend in de-funding public higher education, Berkeley has done much better than other flagship universities in keeping the school accessible to low-income students. Cal has fought tuition hikes, capped the percentage of out-of-state students at 10 percent, and in 2007 created a new office for equity and diversity affairs.

However, none of the population trends in California over the past few decades—the rapid rise of Latinos being the major story—have been reflected in Cal’s population. This is a failure of the school’s diversity goal, which as admissions director Walter Robinson succinctly said, is to have the student body mirror the demographics of the state. The final enrollment tally for the 2009 freshman class was not available for this article, but based on letters of intent, Robinson did find one result: “There has been quite a drop in the yield for African-American students. The biggest drop in the last decade or so.”

A close look at Berkeley’s recent history puts the post-racial ideal in sharp relief. When in 1996 Proposition 209 ended affirmative action in California public higher education (a policy that still held firm with the Supreme Court), it was a big blow to Berkeley’s efforts in minority recruitment. But even during the affirmative action years, Berkeley’s power to create a diverse campus relied, as it does now, on the composition of the applicant pool, which in turn depended on K–12 education, and so on. Berkeley does “have a number of programs that work on college readiness for kids in the K–12 system,” notes astrophysics Professor Gibor Basri, who was appointed to the newly created Vice Chancellor of Equity and Inclusion post in 2007. Unfortunately, current efforts are “a drop in the bucket.”

Achieving equity is a thorny proposition; it’s not just that the field is not level—the referees keep changing the rules. Legal restrictions on affirmative action, in addition to ever-shrinking budgets keep putting diversity goals further out of reach. How, then, to measure merit in a world of uneven opportunity? How can admissions departments remain color-blind while accounting for the lingering effects of historic racial stereotyping? So far, these questions have yielded imperfect answers, but ignoring them won’t make the problems go away—and assuming inevitable progress towards equity, in education and elsewhere, would be a mistake.

Before anyone cared about fairness, gaining admission to the most elite colleges was simple. You just had to be a white man who went to the right prep school. It was only in the 1920s that the Big Three—Harvard, Yale, Princeton—decided they needed to relax the classics requirement in order to widen the admissions pool. With less-stringent academic prerequisites, however, they found themselves with a new “problem”: too many Jews. Apparently, in 1918, even a 4 percent Jewish campus was too much for Princeton. As Berkeley sociologist Jerome Karabel explains in the book The Chosen, the practice of looking beyond academic achievement to other qualities that make the “well-rounded” student—which would later become the basis for affirmative action admissions standards—began as a way to weed out, not include, a particular minority.

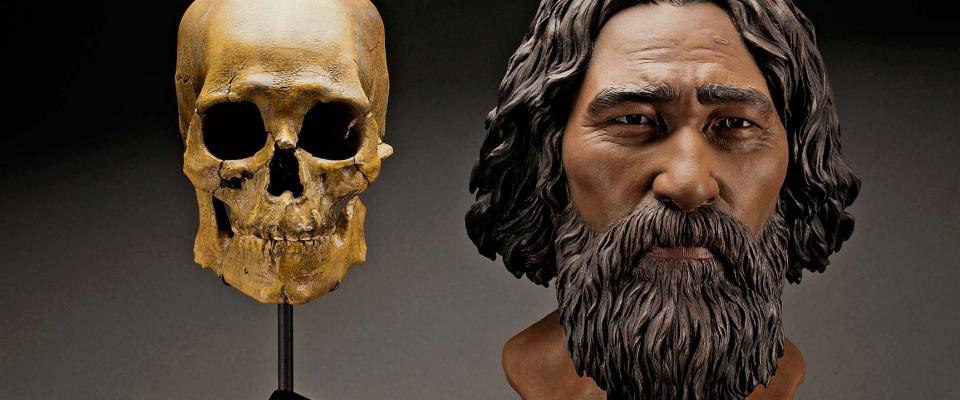

As the founding college in the public UC system, Berkeley has always had a responsibility to recruit a broad range of Californians. Education’s ability to open doors historically sealed was recognized by the founders, who wrote in the 1868 charter that the selection of students by the president should also be free of secular and political influence; that the student body should have proportional representation with the state’s population; and that tuition was to be free to all California residents. (Obviously, not all promises were kept.)

These days, Berkeley acts more like an elite private than like a public school in its admission process. Having many more applicants than it can accept is a relatively new problem: Hyperselectivity didn’t begin until 1980, when the enrollment limit of 30,000 was reached and Berkeley began rejecting more and more eligible students. In 1975, 77 percent of applicants were let in; by 1995, it was 39 percent; and in 2009 it was 21.6 percent.

“For private institutions, such an increase in demand over supply was a phenomenon to flaunt…. For public institutions, the net result was a policy conundrum,” writes Berkeley Senior Research Fellow John Douglass in The Conditions for Admission: Equity, Access and the Social Contract of Public Universities.

Coupled with the challenge of accommodating enough of the students who applied was an increased awareness of race issues. In the wake of the 1978 California Supreme Court decision Bakke v. Regents that confirmed the legality of race-conscious admissions, California put a high premium on upping the number of underrepresented minorities at Berkeley. Under President Saxon, Berkeley instituted a tiered admission policy in 1981, designed to tip the balance for athletes and others with specific talents such as singing or debate, people from rural areas, the disabled, and underrepresented minorities. UCLA followed suit, and together the two biggest UC research universities did indeed come closer to racial parity than in the past.

Although that model has many champions, opponents of affirmative action have continued to bemoan a system that sorted opportunities, even in part, by race. Increasing diversity came at the cost of rejecting some members of “overrepresented” groups, though they had higher test scores, GPAs, and other compelling aspects for admission. These debates came to a head in the early 1990s, when activist UC Regent Ward Connerly began to campaign to remove race as an admissions “plus.” He prodded the Board of Regents to use a “comprehensive review” system that eliminated race but kept other social and economic factors as part of the admissions process. He also spearheaded Prop. 209 in 1995, which outright prohibited public institutions from considering race, sex, or ethnicity in admissions.

Despite a raft of lawsuits from the NAACP and others, the policy stands. “I think to look at race would be helpful,” admissions director Robinson said. “But it’s beyond my wildest dreams that [Prop. 209] would be overturned.”

After Prop. 209, Berkeley moved to a more holistic system that put achievement in context—causing some to protest that Berkeley’s admission policy is “affirmative action by any other name.” In 2003, Regent John Moores publicized an internal memo charging Berkeley with admitting too many underqualified students. More recently, Regent Connerly criticized a new policy approved in February, saying that it was designed by racist “social engineers” at UC who feel that “the only way to reduce the Asian presence is to de-emphasize academic achievement.”

Robinson is unmoved by Connerly’s arguments. The new requirements, which take effect in 2012, don’t have any bearing on Berkeley, he said, because the University’s process is modeled on the elite private schools. “We don’t even screen for UC eligibility,” he said. “All admissions policies advantage or disadvantage someone.”

In this environment, then, Berkeley and other UC schools have had to rethink their approach to diversity. Many have suggested that socioeconomic status would be a better measure of opportunity than race or ethnicity. Unfortunately, the available research suggests that class and race are not interchangeable. In their 2005 book, Equity and Excellence in American Higher Education, former Princeton President William Bowen, Martin A. Kurzweil, and Eugene Tobin evaluated underrepresented minorities who attended 19 elite schools. Those who came from educated and higher-income families underperformed—that is, they did not do as well as other students with similar GPAs and test scores. This was not true, however, of students whose parents didn’t attend college or who came from poor households.

To further test their hypothesis that race matters, they sought answers to the thorniest question: Are the economic and social disadvantages of poverty the same across racial groups? The results were clear: They found that African-American and Latino enrollment plummets without affirmative action. In the experiment, minority enrollment at four public institutions, including UCLA but not Berkeley, went from 17.4 percent down to 8 percent. The authors strongly advocate affirmative action policies for a diverse campus: “We do not accept the proposition that it is only minority students from poor families who should receive special consideration in the application process.”

When this situation played out in California after Prop. 209, the underrepresented minority populations did fall. To add insult to injury, these numbers dipped even while the population of minority high school students was exploding. In 1995, 78,350 African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans graduated from high school; in 2002 that number ballooned to nearly 145,600.

“If you look at the original charter for the University of California, the university is here to help utilize the state’s resources. It used to mean mining the agriculture; now it’s mining the people,” said Vice Chancellor Basri. “As a public university, if a large swath of the state’s citizens are being left out, we can’t claim to be fulfilling that mission.”

But admissions is only one way to measure diversity. The students have to attend. It’s a testament to the strangeness of elite-university admissions that although the vast majority of California’s underrepresented minorities don’t qualify for Berkeley, the minority students who do are hotly courted. There is evidence that Cal is losing them to other schools. In 1999, around 16 percent of underrepresented minorities admitted to the UC system went on to attend private institutions. In 2002, it was 24 percent. Berkeley can’t compete in this arena as well as other schools can, said Robinson. Not only are race-based grants illegal at a state university, but all financial aid packages are feeling the squeeze from a withering state budget and a relatively small endowment.

The other marker of a successful diversity program is, of course, graduation rates. Robinson said that overall graduation rates at Berkeley are good—90 percent, measured over 6 years—but the picture for certain minorities is less rosy. According to the Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, in 2006 there was a 16-point gap between graduation rates of black and white students. Under Chancellor Birgeneau, Berkeley is making efforts to consciously foster better policies around diversity, which will help keep students in school. Vice Chancellor Basri has identified 26 different programs that provide minority students with a range of support—from leadership development and life advising, to help with financial aid issues—to overcome obstacles that make it “difficult to stay here.

To attract in-demand students, the Cal Alumni Association (which publishes this magazine) established the Equity Scholarship this year as a four-year, merit-based grant worth $20,000 per student for underrepresented minorities. Family income, GPA, ethnicity, and whether they are first-generation college-goers were all factors in the selection. But the scholarship had to come through the Alumni Association, which operates independently from the University and thus is not under the mandate of Prop. 209. “I haven’t heard any pushback [from alumni],” the scholarship’s director Michelle Gahee ’89 said, noting that the scholarship was merit based. “Really, what can you say? These students haven’t received any preferential treatment in admissions. This is money for low-income students, for scholarships … it’s not taking away from any other group.” In its inaugural year, the scholarship has been given to ten students, but Gahee hopes to create a $10 million endowment within five years.

To spend any time working in diversity issues is to acknowledge the lingering inequalities in American life—inequalities that access to education is supposed to help fix. Berkeley’s work to prioritize diversity through the creation of a high-level administrative office, and through crafting an admissions policy that doesn’t depend on problematic measures of merit (such as standardized tests), is admirable. But given the many obstacles, it is not enough. And as admissions director Robinson said, with a wry note, America can’t be considered post-racial while equity in higher education remains a distant “great aspiration to have.”