The Tea Party gets all the press, but the Millennials are the future.

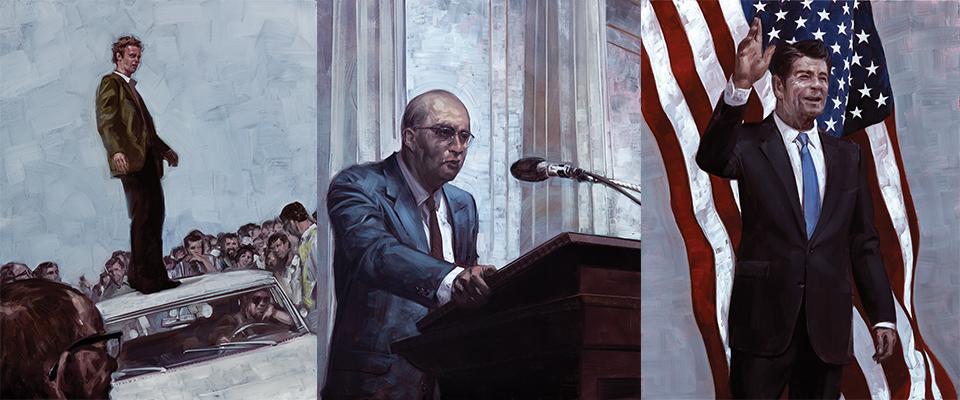

On a swampy day in June 1988, I found myself—a 16-year-old skate punk with a dim view of politicians—at the Ronald Reagan White House. Specifically, I was at the backyard tennis court for a celebrity tournament organized by Nancy Reagan (my dad worked for one of the corporate sponsors). The theme: Just Say No to drugs. I sat sweating in the stands, one row behind the Gipper himself.

While the Reagans watched, a doubles team that included Treasury Secretary James Baker—the bureaucratic warrior who would later spearhead George W. Bush’s Florida recount campaign—demolished Secretary of State George Shultz’s squad.

There were celebrities, too: Herschel Walker, the Dallas Cowboys running back, sported a high-top fade. Chuck Norris wore short shorts and looked more ordinary than action-figure. Umpire Dick Van Patten, the Eight is Enough patriarch, spiked his commentary with Borscht-Belt jokes about his wife’s shopping habits. Johnny Depp, a high-school narc on 21 Jump Street, skulked around the court in dark sunglasses, looking like he wished he were somewhere else.

Afterwards, the First Lady, a birdlike, immaculately coiffed figure, handed out $50,000 checks to nonprofits pushing the Just Say No mantra. The master of ceremonies thanked her, “for bringing to America the drug problem that is afflicting all of our young people.” An unfortunate malapropism.

There’s a generational lesson here. Many in attendance that day were members of the so-called Silent Generation (born between the Great Depression and World War II), a group with a distinctly binary take on the world—black/white, right/wrong, Just Say No. To them, Reagan’s homespun pieties were akin to the revealed word. The presidential staffers, meanwhile, were primarily Baby Boomers (born between World War II and the mid-’60s), an army of GOP apparatchiks in country-club wear who had chosen the conservative side of the nation’s interminable culture wars. On many days that year, you might have found a different set of Boomers outside the White House gates, protesting Reagan’s nuclear policies.

Depp’s 1963 birthday puts him on the cusp between the Boomers and Generation X; nevertheless he strikes me as Generation X personified—aimlessly anti-authoritarian, a Hunter S. Thompson minus the politics. As everyone knows, us Xers (born mid-’60s to 1980, roughly) are the cynics, the slackers, the ones who mainstreamed ironic detachment. In a 1988 Pew poll, only 24 percent of Xers agreed with the statement, “I’m interested in keeping up with national affairs.” As the pollster Peter D. Hart, who is also a Cal lecturer and adviser, noted a decade later, a mere 17 percent of us believed that institutions (whether government or corporate) had anything to offer us. My generation grew up assuming that everyone was lying to us, and we were mostly right. No surprise, then, that the guys behind South Park—who hate fundamentalist Christians and Hollywood liberals in equal measure—are Xers.

Back home, I reacted to the tournament in a typically Xer way: I savagely mocked it with my friends, then I rolled a joint.

Two decades on, it’s remarkable how little everyone has changed. The Silents and Boomers are still fighting the culture wars—look no further than the TV pundits (and their viewers) who keep the anger machine humming. The median Fox News fan is more than 65 years old; MSNBC’s Keith Olbermann’s average viewer is a spry 59. Moreover, Silents and Boomers make up three-quarters of the Tea Party, a group that has benefited from public services all its life and now can’t see why it should help pay for schools or fight climate change. Xers, meanwhile, have generally charted a hedonistic, apolitical course. We spend more on hair care than anyone else, according to Nielsen, and more on home remodeling than any previous generation, a Harvard study found. Indeed, wherever you find home-design porn (Dwell’s median reader is 44), Motörhead onesies, or “locavore” restaurants, you’ll find Xers.

Together, our generations ran the country into a ditch. Two intractable wars, the worst environmental disaster in American history, our bankers exposed as essentially a criminal gang—no wonder the polls show that so much of America is on the wrong track. The media, with its inane dissections of the latest micro-scandals and looping images of frothing Tea Partiers demanding Barack Obama’s impeachment, doesn’t help. Clearly, we’re doomed.

Enter the Millennials, born between (roughly) 1980 and the late 1990s. You’ve probably heard the rap on them. Thumbs fused to cell phones, short attention spans, hardwired for self-absorption, they are the true descendants of the “Me” generation, the fullest expression of our “culture of narcissism,” as New York Times columnist Ross Douthat (himself a Millennial) put it recently.

All of this is true. I teach journalism at an art school in the Bay Area, and most of my students are Millennials. It’s almost impossible to tear them away from Facebook. They’re impatient; they want to skip news-writing basics and get right to more exciting stuff, like opinion writing, where they can express themselves. Nor do they have a great grasp of recent history. Few of them could tell you much about the Iraq war, let alone the Cold War.

And yet I’m filled with hope. The Millennials are, by a mile, the most liberal generation in almost a century. Henry Brady, dean of Berkeley’s Goldman School of Public Policy, calls it a “tremendous generational shift,” and if anything that’s an understatement. Indeed, America’s largest and most diverse generation ever—just 61 percent are white—is also the most tolerant. According to a February report by the Pew Research Center, 50 percent support gay marriage (versus 24 percent of Silents), and according to an earlier Pew survey, only 30 percent believe “immigrants threaten our values.” Not surprisingly, racial attitudes have changed, too. According to a 2007 Pew survey, in 1987 just 56 percent of Xers thought it was OK for whites and blacks to date each other; 30 years later, 89 percent of Millennials did.

These attitudes have political impacts. Millennials got Obama elected in 2008, voting for him by a more than 2–1 margin while the rest of us split almost evenly. Even in this season of dysfunction, when more than one in four Millennials is unemployed, 53 percent of them still say that “government should do more to solve problems”—a decidedly liberal sentiment. Only 39 percent of Silents, by contrast, agree.

They care about the environment, too. Fifty-eight percent believe we should prioritize environmental protection even if it means slower economic growth, according to a 2005 Gallup poll. (The Gulf oil disaster might have pushed these numbers higher.) Millennials might have to Google Three Mile Island, but “You’d be hard-pressed to find somebody my age who doesn’t believe in global warming,” Lillian Mongeau, a 28-year-old Cal graduate journalism student and former Teach for America volunteer, tells me.

The question, of course, is when Millennial beliefs will translate into greater governmental action. Few observers think they will have as much of an effect on this fall’s midterm elections as they did in 2008. The media certainly doesn’t. Judging by column inches alone, you might think that “Old, Disgruntled, and White” is the future of our polity. Mainstream news organizations have assigned legions of reporters to the Tea Party beat (all of those Obama-as-Hitler signs make for great TV), and they appear to have forgotten that Millennials exist. There is some justification for the decision: Midterms reliably attract the angriest out-of-power voters, and the governing party generally gets shellacked. Further, Millennials appear to have cooled a bit on Obama. February’s Pew survey reported that his popularity with Millennials had dropped from 73 to 57 percent.

David Smith, a 30-year-old who as a Cal engineering undergrad helped found Mobilize.org, a nonprofit that aims to engage Millennials, won’t be surprised if they go missing this fall. Smith, now executive director of the National Conference on Citizenship, chalks it up to a generational attention-deficit disorder. “You vote for change and you’re used to instant gratification and you get it on election night,” he says. “But then you realize, ‘Oh, wait, it’s governing.’ And governing moves at a very slow pace.”

Still, it’s just a matter of time before Millennials come to dominate our elections for good. The numbers tell the story. Noisy as they are, only about 5 million people—or 18 percent of the electorate—call themselves Tea Partiers. And as Peter Leyden, founder of San Francisco new media startup Next Agenda and coauthor of a 2007 study on Millennials, reminds me, the Tea Party is on the wrong side not just of history but of demography. “Every year, another 3.6 million Millennials become eligible to vote, and zero more 60-year-olds become eligible,” he says. Moreover, by 2016 all 80 million Millennials will be of voting age. “Demographically, they’re just starting to flex their muscles.”

That afternoon at the White House, I stood in the rope line, stunned by the heat and the forced bonhomie, waiting to shake the president’s hand.

I wish I could say my teenage brush with Washington politics spurred me to action, but it didn’t. Just Say No obviously wasn’t the solution, but I didn’t feel like I could do anything about it. Somebody else was in charge. Like many of my cohort, I drifted through college and into my 20s. I voted regularly—which probably marked me as one of the more politically engaged Xers (our turnout swung from a solid 51 percent in 1992’s presidential election to a wretched 40 percent in 1996 and 42 percent in 2000)—but nothing more. Smith, the Mobilize.org co-founder, summed it up bluntly: “You guys set the bar pretty low.”

They may not always vote but Millennials are more engaged than Xers were—if not always with politics per se then at least with the world at large. You see it in their high rates of volunteerism: According to a 2006 survey, 71 percent of college freshmen had volunteered in the previous week.

More Millennials, too, are interested in careers in public service. Teach for America applications reportedly rose 37 percent from 2007 to 2008. Berkeley’s new “Global Poverty & Practice” minor, a Peace Corps–esque field in which students build houses in Bolivia, say, or work in a Zambian health clinic, is the fastest growing on campus. After her stint with Teach for America, Mongeau, the J-school student, decided to become an education reporter. She now covers Oakland public schools for a Cal-affiliated “hyperlocal” community news site, OaklandNorth. Earlier this year, she received an award for public service.

Smith guesses that Millennials’ civic-mindedness is the flipside of that “culture of narcissism”: “We were raised by Boomer parents who told us to make sure that you’re doing something you love, and that you’re making a difference.”

To me, that engagement—and the hope it implies—might be the biggest difference between this rising generation and its predecessors. Despite climate change and political gridlock and the Great Recession, they’re optimistic—41 percent say they’re satisfied with the way things are going in America. (If that doesn’t sound like much, consider that only 14 percent of Silents feel that way.) The conventional wisdom says that’s just youth; they’ll soon smarten up and see the world for what it is. That’s not how Mongeau thinks. Like Smith, she sees an upside in a trait others often criticize: her generation’s tech-savviness.

“There’s more of a feeling that the world is at your fingerprints,” she says. “Anything you want to know you can find out in ten seconds on Google. It changes the way people think about things.”

They become, she says, “interconnected and solvable as opposed to being impossible to understand.”