A Hemingway photo captures a single, fragile victory.

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the beginning of the Spanish Civil War, which Ernest Hemingway covered as a newspaper correspondent. Hemingway was well paid as a correspondent—he was Ernest Hemingway, after all. His first two novels, The Sun Also Rises (1926) and A Farewell to Arms (1929), had been publishing sensations, and his provocative image—handsome, combative, hyper-male—made him the subject of much discussion.

Hemingway made four extended trips to Spain to cover the war, putting himself at considerable physical risk. Some of the articles he wrote have the qualities of his best fiction, being ironic, knowing, and packed with strong feeling. He was able to render the horror of a war in which civilian populations were being purposely targeted, where vicious reprisals followed an enemy’s conquest of this or that region. In less than three years, half a million people died in Spain, whose population at the time was about 22 million. To put this in rough perspective: In the American Civil War, by far the deadliest in our history, 620,000 died out of an American population half again as large as Spain’s.

The Spanish Civil War, distant in time, remains for some Americans a touchstone, an unhealed heartbreak. If only the world had stood up to Fascism there, on the Iberian peninsula, the catastrophe that ensued—World War II, with its many, many millions dead—might not have happened. Hitler’s Germany and Mussolini’s Italy, intervening in the Spanish conflict, effectively determined the outcome, and their success emboldened them dangerously. Thereafter, admitting no limits to their ambition, they sought world conquest.

My head was blissfully empty of thoughts of global wars or Spanish tragedies when I made a recent visit to the Bancroft Library. I was researching a topic for the Sierra Club, which had hired me to write commentary for a coffee-table book. I ordered up the documents I needed and sat back to wait.

Very quiet there in the Bancroft. On the morning I visited, only three other researchers were at work in the light-filled reading room, all of them wearing clean white gloves to protect the documents they were handling. My research materials had not arrived, so I began to look at the Online Archive of California, a long list of the Bancroft’s holdings in alphabetical order. Near the top, I saw “Abraham Lincoln Brigade photos from the Spanish Civil War, and views of the Mexican Revolution of 1929.”

I like old photographs; who doesn’t? I ordered up this file, and it appeared at my workstation immediately, as if it had been waiting for years to be summoned up from the deep Bancroft vault.

I knew the Abraham Lincoln Brigade had been part of the International Brigades, the organization of foreign volunteers who fought in Spain on the Loyalist side. The Loyalists were the constitutionally elected republican government of Spain and its left-wing and liberal supporters, against which disaffected right-wing military officers launched a rebellion on the evening of July 17, 1936. At first led by General Emilio Mola, a military governor, the rebellion soon came under the total control of Francisco Franco, a skilled, ruthless military tactician whose political instincts were also very acute. When the coup seemed likely to fail early on, Franco made direct appeals to Hitler and Mussolini, who sent hundreds of warplanes and tens of thousands of troops. Franco’s preeminence among the Nationalist generals depended on his military skills, but also on this direct connection to the Fascist leaders.

The Abraham Lincoln Brigade photo-file contained hundreds of shots from the brutal black-and-white war. There were views of cities under bombardment; of refugees fleeing; of ambulances and first-aid stations; of soldiers dressed in a variety of woolen uniforms. I couldn’t be sure that any of the men depicted were actual Brigade members—and, as I later learned, the photographer himself had not been a Brigade volunteer. Whoever he was, he seemed to have been documenting the entire war as it came at him pell-mell, shooting first and worrying about coherence later.

Here was a folder of large prints, some of them stunning, electrifying. Here was another containing many individual contact sheets, with 24 thumbnail photos per sheet. I put on some white gloves of my own, got a magnifying glass, and started examining them. There were shots of schoolchildren, of soldiers in hospital beds, of refugees traveling a wintry road. The cumulative effect was of immersing oneself in a reality that looked uncannily like the Spanish Civil War depicted in movies and books. All the details were right—the primitive automobiles, the soldiers jauntily smoking cigarettes, the wintry locales (some battles were fought in deep snow, in some of the worst winter weather in Europe in a quarter-century).

Here were photos of some Russians … at least, they looked like Russians to me. I knew that the Soviets had been all over the war, that the Loyalists had been able to hold out against Franco and his German and Italian overlords only because the U.S.S.R. sent arms and advisors. Some of those advisors had been political officers, that is to say, intelligence agents. The Soviet secret police at the time were the NKVD; the military police were called GRU. Here were some shots of Soviets with Spanish children. “You see,” the pictures seemed to say, “we Communists are your friends. We are kind to children and small animals. Do not fear us.”

It was a whole war, there in the photos, hundreds of foreign scenes and faces, everything immediate and intensely vivid in the photographic sense. And here was a face I thought I recognized. It was Ernest Hemingway’s face—Ernest Hemingway, photographed as he went about his war reporting.

He stood in a group of four men, all of them dressed for cold weather. There was a single tree in the photo, just behind Hemingway’s head. It marked him out subtly, as though the photographer had been trying to highlight him. I looked up from the contact sheet. I wanted to wave to the archivist standing across the room. “Hello there,” I wanted to call out, “You know what I just found? A previously unknown photo of Ernest Hemingway. Yes, that Ernest Hemingway, the Nobel Prize winner. Come take a look.”

Maybe the photo was valuable. Maybe it would change literary history! But then I calmed down; I didn’t call the archivist over. Who knows? Maybe I’m the only person who still gets excited about Hemingway in Spain. The last 50 years have been pretty rough on the reputation of the hardboiled American prose master, with his dark obsessions with guns and bullfights and his sometimes questionable depictions of women. I’d first read For Whom the Bell Tolls, his novel of the Spanish Civil War, when I was 16. It tells the story of a doomed attempt to blow up a bridge behind Fascist lines in some mountains north of Madrid. I thought it was the greatest thing I had ever read, the most romantic and the most exciting. I started thinking of myself as a future bridge exploder—possibly even a future Spaniard.

The thumbnail photo was hard to make out. Hemingway seemed to be listening closely to a shorter man standing in front of him. Two tall, heavy-set men on either side of Hemingway were also listening carefully. As I would learn from some rudimentary research in the coming weeks, the two men were hardworking fellow journalists, one American, one British, but right at the time I wondered if they might not be Soviet agents.

Hemingway was in Spain to work on a movie, as well. In 1937 he wrote and recorded the voiceover for The Spanish Earth, a pro-Loyalist documentary directed by Joris Ivens. Ivens was a Dutch filmmaker who happened to be a Comintern agent (Comintern = Communist International). Hemingway liked Ivens personally and admired the war footage he got. And Ivens gave Hemingway access to the higher echelons of the Soviet intelligence apparat in Madrid. At the very summit of the Soviet contingent, maybe even higher up than the highest ranking Soviet officer General Vladimir Gorev, was Mikhail Koltsov, a Pravda special correspondent who was Stalin’s personal eyes and ears in Spain.

I needed to see the photo better to determine what was going on in it. For $33, the Bancroft kindly provided me with an excellent digital enlargement. Over the next couple of weeks I pored over the enlargement; I consulted other photographic sources, as well, to see if I could find other shots of Hemingway at work.

The Abraham Lincoln Brigade photos had been a gift to the Bancroft, donated by a man named Henry Arian in 1986, on the 50th anniversary of the start of the war. A Bancroft archivist told me that Arian had lived in Mill Valley, and some rudimentary Googling revealed that he had died in 2004. I wondered why Henry Arian had given his collection to the Bancroft and not to the Tamiment Library in New York, which was the principal archive of Spanish Civil War materials in the U.S. When I tracked down Henry Arian’s two sons (Stephen, a retired lawyer who attended Cal, and Richard, a metal fabricator living in Sebastopol), they told me that their father had had friends at Berkeley, professors who had brought him to the attention of the Bancroft.

Arian was born Hendrik W. Wiessing, in Amsterdam. He spoke a number of languages well, and from the age of 17 he was on his own—his father, the Dutch journalist H.P.L. Wiessing, sent him to live with friends in New Jersey. But Hendrik took off, and by his early 20s he was living in San Francisco with an older woman, an actress.

Among various ways he earned a living was to drive a delivery van for a cheese and egg business. He had an instinct for secrecy, according to his sons—like his well-known journalist father, Arian was radical in his beliefs, but rather than participate in strikes and demonstrations he often stood on the sidelines, taking photos.

In 1935 he returned to Europe, traveling on a Dutch passport. The war in Spain was about to break out. The Spanish Republic, inaugurated in 1931, was under siege from many internal enemies. A strike by miners in 1934 was crushed by then little-known Franco, earning him the nickname “Butcher of Asturias.” Workers sometimes killed priests or monarchists, and these killings were given wide currency by the international press, which favored the sources of traditional power in Spain, fearing a Bolshevik revolution in Western Europe.

Those journalists sympathetic to the Republic, many of them from Britain, France, and the U.S., worked hard to persuade their readers that the legitimate Spanish government was not Bolshevik, was not Soviet dominated, and that in any case, it had come to office legally. Hemingway, Jay Allen (of the Chicago Daily Tribune), George Orwell, John Dos Passos, Robert Capa, Ilya Ehrenburg, Andre Malraux, Antoine de Saint-Exupery, Arthur Koestler—these and other prominent reporters believed that telling the truth about Spain would help the Republicans win the war.

And then there was Hendrik Wiessing. Not a famous writer, not a world-renowned photographer—but, as it turned out, a man of remarkable gifts, uncommon resources. Only 27 when the war started, Hendrik published a book in 1937, From Spanish Trenches, a compilation of recent writings from the front. The book is pro-Republican propaganda, advancing a clear doctrine—the Fascists are bad and need to be defeated—but its methods are fact based, and the writings he chose are strong, artful, flavorful, moving. He puts the war in the context of Spain’s long history of factionalism and geographic particularities, of a tendency toward bloody extremes couched in Inquisition-style causes.

Hendrik had not yet set foot in Spain when he published the book. Having become an authority, he decided to go there. Not as Hendrik Wiessing, however: The Dutch passport on which he traveled in 1935, returning to the U.S. in January ’36, shows a return from a second European trip in February ’38 but no corresponding departure for Europe—no legal exit from the U.S., and no arrival in a known European country.

He was not yet a naturalized American citizen; therefore, he did not travel on a valid American passport. So perhaps he had a false one. Why all the subterfuge? There would be disadvantages to come for those who went to Spain as International Brigades members or Loyalist sympathizers. In the U.S., veterans of the Brigade would one day be designated “premature anti-Fascists,” and some friends of Spain would have political problems for the rest of their lives. Perhaps Hendrik had been prophetic, then.

Or he may have traveled under an assumed name because it was more exciting that way. Many writers have pseudonyms, and the famous Soviet agents of the ’20s and ’30s, the Comintern agents, all had aliases, pseudonyms, alternate identities—it went with the territory. Mikhail Koltsov was born Mikhail Efimovich Fridlyand. General Gorev’s real surname was Vysokogorets. Comrade Stalin, as is well known, was born Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili. “Stalin” means man of steel in Russian, and here is a guess about the name that Wiessing used while in Spain: Marcel Acier. A few of the photos at the Bancroft have the name Acier stamped on the back, with the address of a now-defunct New York photo bureau, PIX. “Acier” means steel in French, and From Spanish Trenches is credited not to Hendrik Wiessing or Henry Arian but to Marcel Acier, a man identified by this single cryptic declaration: “I do not desire in the least to be an agitator, nor have I ever brought myself to join any political organization, right or left.”

Marcel arrived in Portbou, Spain, on November 21, 1937. Over the next two months, he would travel widely in Republican-held areas; he would spend tense and thrilling days under bombardment in Madrid, in company with Ernest Hemingway and others; and he would go to the remote south and west of Spain, photographing, taking notes, researching. The subject of his research remains unknown, because he published no books after From Spanish Trenches. In his letters home to a girlfriend in New York, Marcelle Chesse, he urges her to talk about his project to this person but not to that one. He tells her of a radio broadcast he is about to give, hoping she’ll be able to hear it.

Although he signs his letters “Henri,” he advises her, “If you should have to get in touch with me in a hurry, you can send a cable to Acier—Hotel Ripalda—Valencia…. I’ll be back there sometime next week.” So, officially, he is known as Marcel Acier.

As Marcel, he shows a special interest in hospitals and schools. Another special concern of his is children’s homes (or, as he calls them, “children’s colonies,” places where orphans are being sheltered).

“There is so much to see here for me that I sometimes despair,” he writes, and yet he soon leaves Madrid—his main purpose is to document how the revolutionary society is taking care of its weakest members: homeless children. It’s unclear how the now 28-year-old Hendrik, former egg-and-cheese deliveryman, has turned himself into a credible reporter on children’s welfare in wartime, but his charm and energy no doubt have something to do with it. And then there is another factor—his absolute belief in a revolutionary future, in the fight against Fascism.

He meets Hemingway at the Hotel Florida in Madrid, where Hemingway is nesting with a lover, his future third wife, Martha Gellhorn. Hendrik meets other dashing war correspondents, too. One is the youthful photojournalist Robert Capa, like Marcel born in Europe, a speaker of several languages, a handsome charmer, and a friend of Spain. Marcel mentions Capa in a letter home to Marcelle—by December 1937, Capa is world famous for his photos of the Spanish war, including “Death of a Loyalist Militiaman” (a.k.a. “The Fallen Soldier”). Capa is represented in New York by PIX, and it may be at Capa’s urging that Marcel also signs on with PIX.

On December 22, he tours the Mediterranean coastal city Valencia, probably to look at more hospitals and children’s colonies. “My room is filled with oranges and almonds,” he writes his girlfriend, more comfortable here than in wintry Madrid, where food was scarce. But now something other than orphanages captures his attention. There is a battle going on, and it happens to be the Battle of Teruel, the crucial battle of the war, Teruel being a city in the bleak mountains of Aragon, some 75 miles to the northwest.

Teruel has been under Nationalist control for a while, and Franco is about to launch an offensive from there. But the Republicans launch a counteroffensive, with 100,000 troops commanded by their best generals. On December 21, Republican forces break into the city. Hemingway arrives with the first troops, traveling with other reporters, and he files a classic dispatch, “The Fall of Teruel,” about what he sees and experiences. He notes wryly, “We had never received the surrender of a town before and we were the only civilians in the place. I wonder who they thought we were. Tom Delmer, London newspaper correspondent, looks like a bishop; Herbert L. Matthews, of The New York Times, like Savonarola, and I like, say, Wallace Beery three years back, so they must have thought the new regime would be … complicated.”

Herbert Matthews will describe this “surrender” as one of the greatest days of his life. Robert Capa is also among the first to arrive, traveling with a squad of dinamiteros who are fighting house to house. After being under frequent machine-gun fire and forward-marching nine hard kilometers with a platoon of infantry, Hemingway and his companions drive back to Valencia to file their stories and to sleep in their comfortable hotel beds. Marcel makes it to Teruel two days later. Nationalist forces are holed up in a few downtown buildings now, determined to fight on to the death.

“In the morning I hitchhiked with a young officer to Teruel,” he writes Marcelle. “There was excitement [in Teruel]. We had cut the fascists off … and were now in complete control except for a building or so…. All around [were] layers and layers of mountains in a thousand colours like the painted desert…. Just before we got to the town we saw a bombing. We were two villages away.” In nearby Castralvo, he finds “a lot of friends of mine from Madrid … newspaper people. Hemingway was there, and Matthews and Capa and lots of others.”

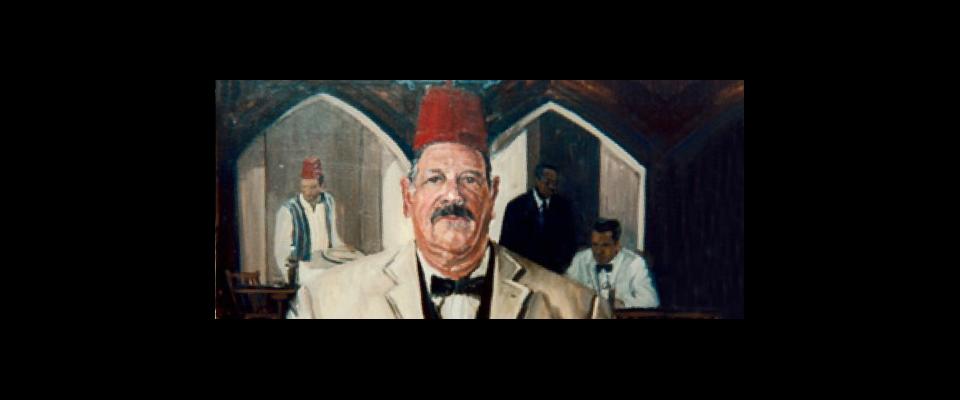

Before continuing on to Teruel, Marcel takes a single photograph: It is the photo of Hemingway in front of the leafless tree. The man to Hemingway’s right (Matthews, of The Times) does indeed look like Savonarola, the religious leader of 15th-century Florence. The other man could pass for a bishop: Sefton Delmer, of the London Daily.

Although not in Marcel’s photo, Robert Capa was nearby, perhaps only a few feet away, taking pictures of his own. His pictures, which show Hemingway, Matthews, and Delmer dressed exactly as in Marcel’s picture, are how we know the exact date and place of the photo Acier took.

That night, after an exciting day of dodging bullets and witnessing bomb attacks, Marcel takes refuge in an old woman’s house in an outlying village. “The old lady and her daughter … did everything they could to please me,” he writes Marcelle. “My bed upstairs was clean and warm, the little wick dipped in olive oil gave me light as it has given light to the Spanish people for centuries.” Before going to bed he enjoys an excellent dinner: “White cabbage and a little 2-inch square piece of bacon and bread. It tasted swell. It was the first hot food I had had in two days!”

The old woman has cooked this repast over a fire of roots and twigs laid directly on the floor of her whitewashed cottage. Half-frozen, Marcel hunches over the cooking stones. It is Christmas Eve. He misses Marcelle, he tells her, and it’s too bad that he won’t get to exchange presents with her, but after all, he has been at Teruel—at a battle that will surely go down in history as “that most inspiring place of our first big and important offensive.”

It is the moment of greatest hope—and also, alas, the last moment of any real military hope—for Republican Spain. Marcel has been taking photos all this momentous day, and it will be interesting to see how they turn out.