The history of the Pacific Film Archive is a love story with film.

The old Berkeley Art Museum/ Pacific Film Archive (BAM/PFA) has moved into their new digs and is now the new BAMPFA. It seemed like a good moment to revisit PFA’s storied history.

On a warm summer night in Berkeley, a diverse group of moviegoers congregates on the south side of campus, just off Bancroft, near the entrance to the Pacific Film Archive (PFA) Theater. The building is sort of a hip take on a Quonset hut—intended as a temporary alternative to the theater in the Berkeley Art Museum (BAM), which has been closed for retrofitting since 1999. Yet, like the eastern span of the Bay Bridge, it still serves dutifully, screening films nearly every night of the year. Tonight a pair of runners whiz by, their physical exertion in stark contrast to the gathering throng of audience members who linger and converse as they wait for the doors to open.

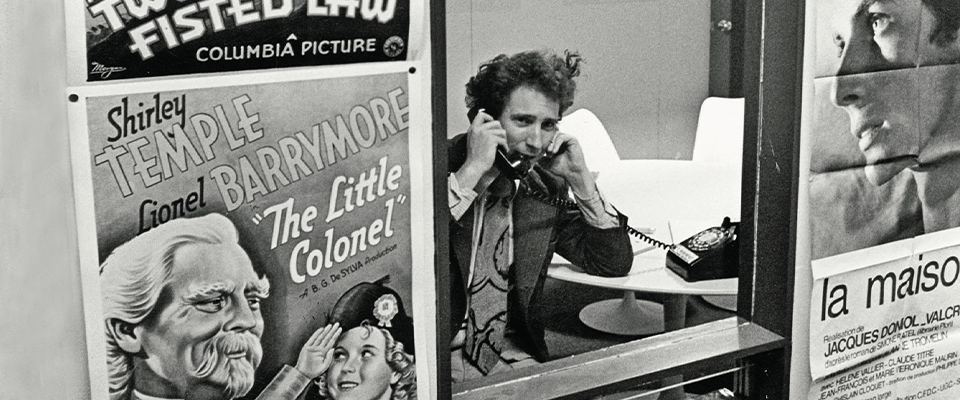

Passing by the vintage Jean Vigo movie poster in the lobby, patrons saunter into the theater and stake out their territory among the 222 comfy seats distinctly upholstered in vivid purple and affording a surprising amount of leg room. Prior to show time, professorial types chitchat about the drudgery of grading final exams, while locals rave about a new line of artisanal hemp handbags. A few folks parlez français in that charming yet slightly intimidating way of Euro expats. Next to them sit rumpled young adults wearing that wan yet agitated look of students who have survived the semester on a steady diet of ramen and Red Bull.

Soon, PFA film curator Kathy Geritz makes her way to the front of the theater to introduce the evening’s special guest: gifted cinematographer Agnès Godard, on hand for a mini-retrospective of her work. Tonight’s selection is writer-director Erick Zonca’s 1998 debut feature, The Dreamlife of Angels, its story of two wayward friends beautifully rendered through Godard’s incandescent Super 16 mm images. After the lights go down, viewers get lost in the film, their immersion never once interrupted by cell-phone texting or popcorn chomping (food and beverages are not allowed in the theater). Geritz and Godard return for a postscreening Q&A session, during which one erudite audience member refers, with studied nonchalance, to French filmmaker Robert Bresson.

Hearing Godard discuss her craft in detail is the sort of treat filmgoers expect at PFA, where cinema and its practitioners—from the universally recognized masters to the little-known up-and-comers—have attracted rarified audiences of viewers and debaters for five decades.

Founded in the mid-1960s by transplanted East Coaster and underground film aficionado Sheldon Renan, who envisioned a university-based forum for film studies, in its nascent years PFA ran on the sort of scrappy determination and hippie economics associated with Berkeley success. As Renan remarked in a 1971 interview, “This whole thing is put together with spit, chewing gum, good intentions, [and] cooperation from the film community. I’m not over budget or under budget, because I haven’t got a budget.”

Working independently on moxie and spare change, Renan formed a network of equally foolhardy cohorts, including critic and lecturer Albert Johnson, projectionist Willard Morrison, and Berkeley student Tom Luddy. In need of more substantial support, Renan appealed to Peter Selz, the forward-thinking director of what was then known as the University Art Museum, to give the budding center for film exhibition and study a home under the museum’s wing. Encouraged by legendary Cinémathèque Française founder Henri Langlois, who recognized all the way from Paris that these ardent Berkeley boys truly knew their cinema history, Selz agreed, and thus the University Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive was officially christened.

A dedicated theater followed some years later; until then, weekly screenings were held at Wheeler Auditorium, where seminal figures such as Jean-Luc Godard and Fritz Lang appeared for retrospectives. Members of the initial advisory board constituted a Who’s Who of the era’s cinema elite: public intellectual Susan Sontag, critic Andrew Sarris, and Film Quarterly editor Ernest Callenbach.

Having established a permanent home for PFA, Renan handed the reins to Luddy, who remained in charge until 1980. (Luddy subsequently cofounded and still codirects the Telluride Film Festival.) Academy Award–winning filmmaker Errol Morris (The Thin Blue Line, A Brief History of Time, Standard Operating Procedure) arrived in 1972 as a Ph.D. candidate in philosophy, quickly abandoning Kant and Heidegger in favor of sitting in the dark and watching film.

“It wasn’t just a place to go and see a movie,” Morris recalls during a recent phone call. “The PFA was my film school. I met Luddy and this odd group of people who hung out there, the crazies, like the woman who always sat in the back row because she was afraid that someone sitting behind her would cut her hair, and the narcoleptic who would sit in the front row every night, fall asleep as soon as the first film started, and wake up just as the last one ended.”

Morris remembers his first exposure to the works of Preston Sturges; visits with Nicholas Ray and Kenneth Anger; and the arrival of New German Cinema directors such as Wim Wenders and Werner Herzog, Morris’s close friends to this day. Conversations often spilled over to nearby Chez Panisse, named by restaurateur Alice Waters after a character in a Marcel Pagnol film. “Would I have become a filmmaker without meeting Tom and Alice and so many filmmakers and spending those years at the PFA? I truly doubt it,” Morris says.

With programming and operations now in place, Luddy stepped down and was succeeded briefly by Lynda Myles, followed by Edith Kramer. Dressed head to toe in black, stylish spectacles perched precariously on the end of her nose, Kramer presided over screenings as the grande dame of film curating for a record 22 years.

Following Kramer’s retirement in 2005, Cinémathèque Ontario veteran Susan Oxtoby signed on as senior film curator. She has since spent her time trying to put her own indelible stamp on the place. Part of the challenge, she says during an interview in the BAM/PFA garden, is presenting about 600 films a year, with few repeats. Being at Berkeley, she says, is a big help.

“It’s exciting to work for a university,” Oxtoby says. “The brain trust is extraordinary here. We’re able to work with many different departments on outreach and with faculty members as guest speakers.”

Oxtoby and her fellow curators, Steve Seid and the aforementioned Kathy Geritz, meet on a weekly basis to discuss program ideas. “We don’t want to skew too far in any one direction over the course of a single calendar, whether it’s the auteur theory or Indian cinema,” Seid says over lunch at Babette, the BAM/PFA café. The trick is to create a balance among single-artist retrospectives and series focusing on particular geographical regions or themes, while leaving room for last-minute additions of prints that have suddenly become available from other archives and preservationists.

The curators do draw upon PFA’s own collection of some 10,000 films and 5,000 videos stored in an undisclosed, climate-controlled location; a “funky playhouse,” according to Department of Film and Media faculty member Russell Merritt. “A place where, for me, every day is Christmas.” But for most programs, the curators are likely to source prints from far-flung locales (an upcoming series on Georgian cinema has taken Oxtoby to Berlin, Toulouse, and Tbilisi for research and haggling). PFA is a member of the International Federation of Film Archives, and as such has access to rare prints entrusted only to members.

Oxtoby and her team often develop their ideas at PFA’s Library and Film Study Center, also open to the public. The center, with thousands of books, periodicals (late-1950s issues of Ciné Télé Revue sit atop a cluttered desk), and program calendars stretching back to the 1970s, is a trove of movie ephemera. Rows of old-school metal file cabinets are stuffed with nearly 100,000 clippings in meticulously maintained film and filmmaker files (one drawer, opened on a whim, stretches from Cannibal Holocaust to Catch Me If You Can).

Along with standard screenings of films new and old, the curators create one-of-a-kind events that augment and sometimes challenge traditional modes of cinema presentation. Some years ago, Seid curated PowerPoint to the People, an evening of live presentations for which competing artists utilized the then-maligned software program. “It was like American Idol, but with PowerPoint. I was really proud of that one,” recalls Seid. “I like the idea of creating an expanded, extended moment, adding a dimensional element of performance to screenings.”

A few years back, Seid curated a daylong program of the multimedia works of vanguard artist Lynn Hershman Leeson, who conducted Q&A sessions via her Second Life avatar. “The audience was thrilled,” Seid recalls, “and never knew that Lynn was sitting only 20 feet away, up in the projection booth.”

Seid addresses the importance of appealing to more than just longtime cineastes. “We never program in a vacuum with no sense of an audience,” he says. “As the cinephiles age, we want to find new audiences to follow them.” This is no small issue for PFA because it is often overlooked by Cal students and Bay Area denizens, despite its stellar reputation among kindred international organizations and devoted cineastes for film presentation, preservation, and advocacy.

Increased visibility is what all of them expect to gain when they relocate to swanky new digs in downtown Berkeley, along with PFA’s cultural and administrative partner, the Berkeley Art Museum, in 2016. Lawrence Rinder, current director of BAM/PFA, certainly believes it will happen.

“Our new downtown Berkeley building will greatly improve our audiences’ experience of film,” he promises. “The Barbro Osher Theatre will be built specifically to achieve the best possible cinema experience, and the new facilities for the film library and study center will vastly improve the accessibility of our exceptional holdings of film-related books and magazines and ephemera archives.”

A new building with state-of-the-art facilities also means new technologies that reach younger and more tech-savvy audiences. Both Seid and Oxtoby, while committed to tried-and-true film formats, have seen no sense in denying digital formats as well. Oxtoby promises that the PFA will show 35 mm prints for as long as possible, but admits that in many cases the best available copies of sought-after films are now in the Digital Cinema Package (DCP) format that is fast becoming the industry standard.

“The digital cinema conversion has been extreme and rapid,” Seid confirms, though he’s concerned that Hollywood studios have only converted a small percentage of their extensive back catalogues to DCP. “It’s definitely more difficult to put together a historical repertory.”

Caught up in the endless distractions of online streaming and YouTube clips, are today’s students as likely to fret over the digital versus film debate, or even drag themselves away from their tablets to attend screenings?

“Interest in film hasn’t declined, but the ways in which younger audiences are discovering cinema have altered drastically,” Seid says. “For them, watching a film on an iPad or cell phone might be an exciting, even life-changing experience.” But, he adds, “it’s our job to coax them into seeing films on the scale and in the quality of presentation for which they were intended.”

One distinct difference between PFA and a commercial movie theater, he points out, “is that we have a distinct cultural mission to place cinema inside an aesthetic as well as a sociological history. We do this by bringing in directors, actors, critics, and other people who help audiences decode films. We see cinema as a way of encountering the world. This doesn’t usually happen at a cineplex, where the main mission is to sell you popcorn and get you in and out as fast as possible. That’s a totally disposable kind of experience, whereas at the PFA we aim to present experiences that can be revelatory.”