The epic poem Layla and Majnun is arguably the most famous love story in the Middle East, and yet many Westerners have never heard of it. It is the tale of two teenagers who fall deeply in love but are tragically kept apart, even until death. After Layla’s father rejects Qays’s request for her hand in marriage, Qays wanders the desert expressing his undying love through poetry.

My soul is on fire because we are apart

I want to join my beloved

My heart is heavy because I am alone

I want to see my beloved

I feel like a nightingale that cries in pain, trapped in a cage.

This earns him the name majnun (Arabic for “crazy”), or more literally, “one who is possessed.” Layla is married off to someone else, dies of sorrow, and when Majnun hears of it, he dies as well.

How could I know that falling in love with Layla would turn out this way?

What could I say, what could I do? I cannot control this love.

I’m powerless—I can only worship this one idol until the very end of my life.

This September, the tale will come to life in an ambitious operatic production commissioned by Cal Performances and at least ten other organizations, including the Lincoln Center and the Kennedy Center. The artists who have come together to build the opera form the ultimate dream team: It includes world-renowned cellist Yo-Yo Ma’s Silk Road Ensemble arranging and performing the music, choreography by Mark Morris and the Mark Morris Dance Group, lighting designs by James F. Ingalls, and set designs and costumes by the British painter Sir Gordon Howard Hodgkin. This is the first time an adaptation of Layla and Majnun is being presented in the Western Hemisphere on this scale.

Though sometimes described as a Middle Eastern Romeo and Juliet, Layla and Majnun is at least a thousand years older than Shakespeare’s play. “The story has Arab roots,” explains Fateme Montazeri, a doctoral student in UC Berkeley’s Department of Near Eastern Studies. The characters have Arabic names—Layla and Qays, meaning “night” and “one who is firm.” They are also believed to be “semihistorical,” found in anecdotes and oral sayings dating back as early as 7th century Arabia. “According to some accounts, however, Majnun (Qays) was not the name of a single poet, but an epithet for any lover with passionate love poems for his beloved,” says Montazeri.

It was the famed Persian poet Nizami, however, who established the tale as part of the world’s literary canon. In 1206, he completed the epic poem Layla and Majnun, and it quickly “became the source of inspiration, as well as imitation, for many later works,” says Montezeri. At least 86 other poets would go on to create their own versions of the story in Persian, Turkish, Pashto, Urdu, Kurdish, and Azerbaijani, among other languages.

In 1908, Azerbaijani composer Uzeyir Hajibeyli took a 15th-century version of Layla and Majnun by Azerbaijani poet Fuzûlî and turned it into what is now known as the first Middle Eastern opera. Hajibeyli combined the Azerbaijani traditional style of mugham, a highly complex modal system of musical improvisation, with Italian opera.

Today, Azerbaijan’s “living national treasure” and most celebrated master of mugham is singer Alim Qasimov. It was Qasimov who, more than ten years ago, suggested that Yo-Yo Ma and the Silk Road Ensemble adapt Hajibeyli’s opera into a more digestible piece for a modern audience. Silk Road Ensemble violinists and composers Colin Jacobsen and Johnny Gandelsman worked to arrange the piece and downsized the original instrumentation to match the size of the ensemble. According to Jacobsen, they also condensed the opera from 3.5 hours to 45 minutes, wanting to blend the sections a little more. Rather than having the mugham section here, and the orchestral section there, he wrote connective tissue to help the piece flow from one section to another, with Gandelsman arranging most of the Western musical numbers. This results in a more orchestral feel at some points, and an intimate one at others.

The Silk Road Ensemble successfully toured Layla and Majnun in 2008 and 2009, prompting Yo-Yo Ma to ask choreographer Mark Morris if he would be interested in turning the piece into a fully staged production. Morris, famous for his commitment to working closely with live musicians, turned it down. He now recalls, “I said no at the time because I wasn’t convinced that I could transform the piece into a viable choreomusical production. After some changes and modifications in the performance version of the music, I decided to take on the project.”

Morris has been working on the choreography and ideas for the set design since September 2015, working closely with set designer and painter Howard Hodgkin. “I have looked at paintings and films, I have listened to related music from the region and by the same composer. I made a brief visit to Baku [capital of Azerbaijan] to get a feeling of the place and to spend time with the marvelous singers and musicians who are involved in this show. I have watched quite a bit of Azerbaijani national dance and listened to a great deal of mugham singing. I and all of my company have read all of the poetry available.”

A production of such complexity has its difficulties, however. “I am trying to keep a lot of balls in the air. It is a big project and a deep one,” Morris explains. “Due to our very complicated schedules, it is quite difficult for us to all collect in the same place at the same time. It makes decision-making rather difficult. I look forward to us all working together in person.”

The improvisational element of mugham, which is essential to the style, further adds to the challenge. Jacobsen suspects that each night of the performance will bring a little of the unexpected. “Alim Qasimov is such a natural performer. I think Mark Morris is used to working with live music, but Alim in the mugham sections is quite free.”

“I was so excited when I heard that an opera had been written on this poem. It has such a heightened reality of emotions, making it perfect for opera,” says Torange Yeghiazarian.

“The improvisational elements are of course difficult to plan in advance,” says Morris. “The form and structure of the piece can vary to a certain degree. We will work out the details of all of the improvisatory sections when we are all in the same room together, which will be just a few weeks before we go into the theater. Let’s just say I’m leaving some things open.”

That fluidity is only one reason for the co-creators’ anticipation and excitement about the premiere. “It’s really amazing for us to have created this thing about ten years ago, and then to see it have totally new life through Mark Morris’s vision,” says Jacobsen. “I just can’t wait to see how it all comes together as a real theatrical thing.”

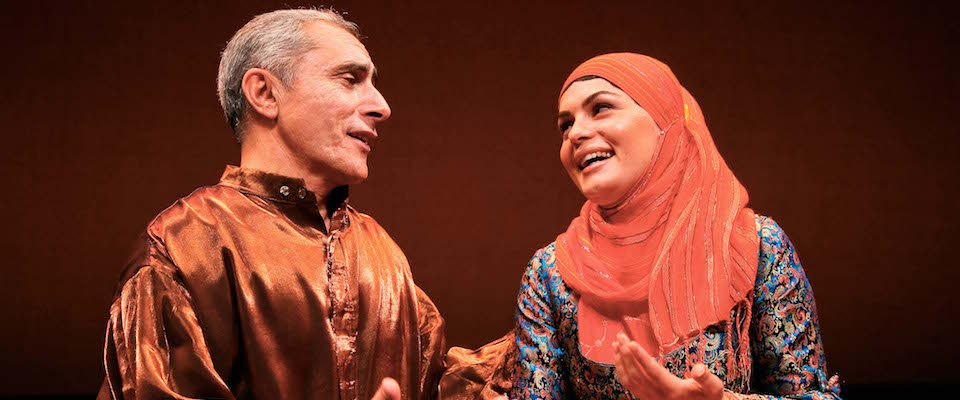

The new production will run a little over an hour and will feature the vocals of Qasimov and his daughter and protégée (and prodigy in her own right), Fargana Qasimova. The two of them will be singing the roles of Layla and Majnun, accompanied by a small ensemble. Instruments will include two violins, viola, cello, and contrabass, providing the orchestral lushness of Hajibeyli’s original opera; along with traditional Asian instruments the kamancheh and the tar (Azeri fiddle and lute), the pipa (a Chinese lute), percussion, and the shakuhachi (a Japanese bamboo flute). Jacobsen says the range of instruments will help to connect both worlds better.

In tandem with the piece’s world premiere at Zellerbach Hall, Cal Performances will present a symposium designed to help educate audiences about the work and its history. Montezeri, who wrote her master’s thesis on the subject of Layla and Majnun, will participate in a panel hosted by Cal Performances. She is very curious how audiences will receive the performance and argues that, no matter how ancient, “love poetry can always be intriguing. Even though the story develops in a traditional Eastern appearance, the modern Western audience may connect to the core of the story—the story of two young lovers who can never unite due to societal restrictions is timeless. This is what we admire and will enjoy watching…. We all feel the urge to fight for something we believe in, without choosing comfort over truth.”

Torange Yeghiazarian, artistic director of a Middle Eastern–American theater company in San Francisco called Golden Thread Productions, is one of many directors, educators, and scholars invited by Cal Performances to present at the symposium. She is developing theatrical activities and a program for teachers to help them and their students better understand the piece.

“I was so excited when I heard that an opera had been written on this poem. It has such a heightened reality of emotions, making it perfect for opera,” says Yeghiazarian, who is from Iran and speaks Persian. She explains how deeply the poetry of Layla and Majnun is woven into the culture. “Growing up, I’d always hear their tragic love used as an example … Someone might suggest that another be sensible in choosing one’s life partner, by saying ‘Don’t be mad like Majnun.’” In Iran, she explains, “poetry is for everybody, not just for educated people. People use phrases or characters from poems every day and fluidly incorporate them into the daily vernacular.”

Yeghiazarian sees this new production as a chance for audiences to connect with the Middle East on a different level. “It’s rare that you see the Middle East and beauty and art and love in the same sentence. It has been so vilified, and every day we are bombarded with images painting us as evil or painting the Middle East as something to avoid, if at all possible…. This poem is so passionate and inspirational, and the descriptions are so vivid, how it paints the surroundings and the lushness and ornateness of the space.” But most of all, to her, “These are human stories” that are important because they “provide a shared human experience.”

Marica Petrey is a frequent contributor to California.