But the architect who designed leisure spaces for women appeared to have none of her own.

In late June, visitors find the doors of Berkeley City Club locked, signs imploring would-be entrants to wear masks. The club, originally imagined as a space to foster women’s civic engagement, was designed by the famed architect Julia Morgan (B.A. 1894). There’s a swimming pool inside, its untouched water reflecting the aquamarine, cloistered arch ceiling above. Where there should be the echo of rhythmic splashing bouncing off tile, there’s a cavernous silence. Though Morgan is best known for her design of the Hearst Castle in San Simeon, not to mention numerous buildings on the Berkeley campus, it is her swimming pools that call out to me these days. As our summer sheltering in place draws to a close, for many it marks the first summer of their lives that they didn’t set foot in a swimming pool. If there were no pools, was it really summer at all?

Despite her many pool designs, Morgan wasn’t much of a swimmer. But she was comfortable in places where she didn’t belong. When she arrived at Berkeley in 1890 to study engineering, she was often the only woman in her math and engineering classes. Her younger brother chaperoned her commute by horse-drawn street car from their home in Oakland to the campus, until she moved into the Kappa Alpha Theta sorority house, an experience of a communal women’s space that would shape the rest of her career—not as an engineer, but an architect. While studying at Berkeley, she encountered Bernard Maybeck, the famous Bay Area architect who would become her mentor and, later, her collaborator.

Morgan went on to become the first female student to earn an architecture degree at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, where she reported that her instructors “always seemed astonished if I do anything that shows the least intelligence.” Upon her return to California, she became the first woman to get an architecture license in the state. Even in death, she is still racking up firsts, as when she became the first woman to win the American Institute of Architects Gold Medal in 2014.

Catastrophe kick-started Morgan’s career. In 1906, the San Francisco earthquake struck. A belltower Morgan had designed on the Mills College campus miraculously survived, which sent more clients flocking to Morgan’s firm in the building boom after the quake. Her work caught the eye of Phoebe Randolph Hearst, a philanthropist and major benefactor of UC Berkeley, and it was through her patronage that Morgan embarked upon some of her most ambitious projects.

She was prolific, averaging 15 buildings a year to Maybeck’s two, which resulted in more than 700 buildings ranging from private homes to women’s clubs, and William Randolph Hearst’s “castle” in San Simeon. On the University’s campus, Morgan designed Girton Hall (now Julia Morgan Hall, which was relocated to the UC Botanical Garden in 2014), Hearst Gym (a collaboration with Maybeck), and a private home that is now used by the Department of Demography, not to mention other private homes that would eventually be inhabited by student groups. Many of her designs were quintessentially Californian, drawing on rustic Arts and Crafts styles but also more classical modes for inspiration.

Presumably out of necessity in a famously male-dominated field, Morgan adopted an androgynous style. Like her male counterparts, she wore a dress shirt and tie, but with a skirt instead of slacks. Her round spectacles gave her a serious, owlish look. Professionally, she was known by the degendered “J.M.”

Though it seems that she often tried to conceal her sex in order to advance professionally, many of her designs were for female spaces. She designed numerous YWCAs in the West, as well as sorority houses and women’s gymnasiums.

Little is known about Morgan’s personal life. She had no known romances, left no writings, and rarely gave interviews. She was so consumed by her work that it seems she barely stopped to eat. “Her muse was the grindstone,” Architect magazine noted. The woman who designed leisure spaces for women appeared to have none.

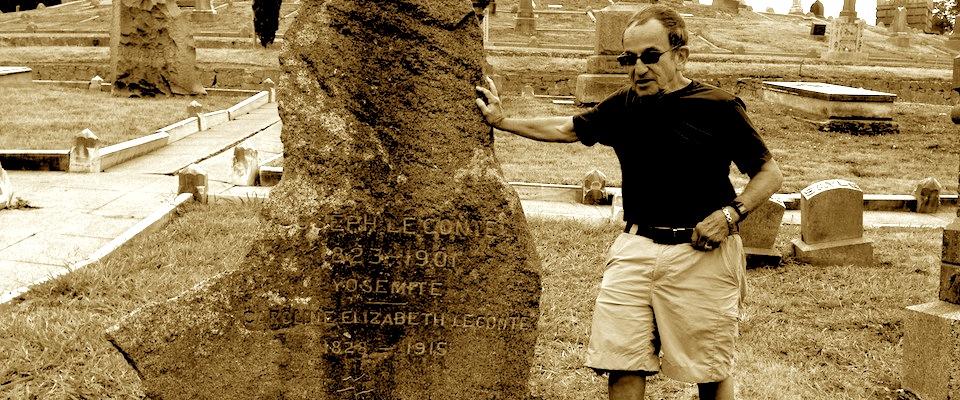

Before she died, she destroyed her blueprints. The buildings would speak for themselves.

***Corrections: A previous version of this story mistakenly described Julia Morgan Hall as a childcare center. The hall, which was relocated to the UC Botanical Garden in 2014, now serves as a venue for a variety of social events. The total number of buildings designed by Julia Morgan was misstated. There were over 700 buildings, not 70.

From the Fall 2020 issue of California.