Health and medicine historian Elena Conis puts coronavirus into perspective.

Elena Conis is a historian of U.S. public health and medicine, with a special focus on the history of infectious disease, environmental health, and vaccines. She is also the director of the joint graduate program in public health and journalism at Berkeley.

The current COVID-19 pandemic is often compared to the 1918 flu pandemic. How valid do you think the comparison is?

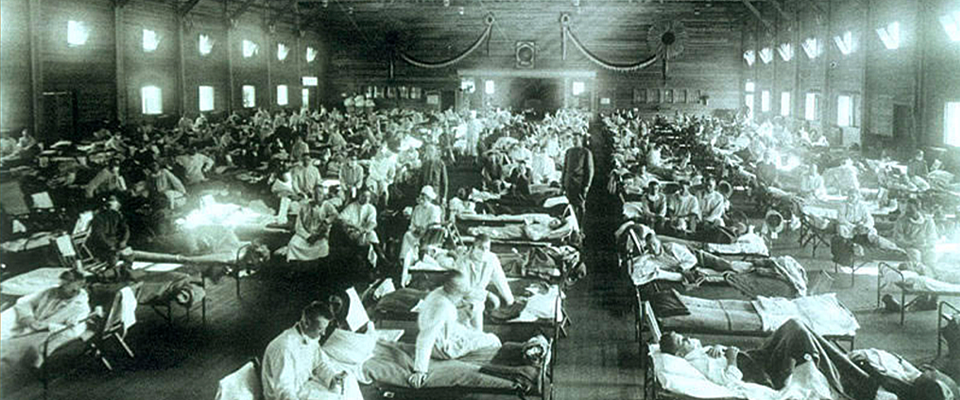

Elena Conis: You could make comparisons to many historical epidemics, and they would all be valid in one way or another. The 1918 flu was frightening and destabilizing, and it both overwhelmed our capacity to deal with it and exposed how social patterns contributed to the spread of disease. Cities ordered people to stay home from work, avoid gatherings, and wear masks in public. And significant numbers of people refused to heed those directives. All of that feels familiar now. But at least two key differences are that that flu killed more people in the U.S. than COVID-19 has—yet—and that it, like all flu epidemics, passed with the end of flu season, and we have yet to determine what type of seasonal pattern, if any, COVID-19 will ultimately display.

Compared to our current situation, do you think it was easier to implement quarantines and lockdowns in past pandemics?

EC: In the U.S., we have always had those who resist the infringement of individual liberty in the name of public health. In the past, there were moments, places, and situations in which force was used to ensure compliance with public health directives, from quarantines to mandatory vaccines. In too many cases, that force—the police power of public health—was felt most acutely by groups already oppressed, including immigrants, people of color, and laborers. I’m hesitant to say it was easier to implement quarantines and lockdowns in the past, but I will readily point to examples in which the police power of public health was unevenly applied.

Since the outbreak, you’ve written about the polio vaccine and the 1832 cholera epidemic. How do those episodes inform the current situation?

EC: I believe history has tremendous power to give us perspective on the present. There is a tendency to think of our current situation as unique and unprecedented, and in many ways it is, because no moment in the past looked quite like our present moment. But throughout history, we have dealt with devastating pandemics that have rattled society, tanked the economy, pitted us against one another, reshaped our environment, and fundamentally changed how we live our lives. The study of past pandemics shows, in short, how we’ve adapted to new pandemics repeatedly—and how sometimes that adaptation happens over the course of centuries or millennia.

People have been talking about how COVID-19 will change the way we live. How have past pandemics permanently changed society? And what changes do you foresee from this pandemic?

EC: I’m reluctant to make predictions about the future—so I won’t! But past pandemics have shaped us in so many ways. Cholera epidemics of the nineteenth century helped prompt us to prioritize urban sanitation, clean water, and plumbing. Mosquito-borne diseases from yellow fever to malaria made us aware of environmental conditions that allow such diseases to thrive. Our experiences with plague and smallpox gave us the basic tools of public health, from quarantine and sanitary cordons to vaccination. The list goes on.

Many experts believe that a vaccine is the only way we will end the current pandemic. Do you think that will lead to greater public acceptance of vaccinations?

EC: We would be so fortunate to develop a safe and highly effective vaccine, and we’d be especially fortunate if we develop one within the next few years. But one thing that the history of vaccination shows is that vaccines have been contentious technologies and vaccination a contested practice—especially when made compulsory—ever since the very first vaccine was developed, against smallpox, in the late 1790s. In the U.S. we have had moments of greater and lesser vaccination acceptance in the last 200-plus years, to be sure. It’s hard for most people to believe this, but we are currently living in an era of unprecedented vaccination acceptance, because we vaccinate more children against more infections with more vaccine doses than any society or generation has before us. We are certainly also living through a moment of outspoken vaccination resistance. Personally, however, I am more worried about how social inequities will determine who gets vaccinated, with what vaccines or vaccine doses, when, and under what conditions.

From the Fall 2020 issue of California.