FROM THE MICROPLASTICS LEACHING from our laundry to the Styrofoam swirling in the Pacific garbage patch, it seems the world is awash in plastic waste. While we have struggled and failed to wean ourselves off plastics, Berkeley scientists are working hard to address the problem by making polymers that are more readily recyclable and biodegradable.

While the team enthusiastically announced the new material in 2019, major questions over the costs and logistics of introducing PDKs to the market remained.

Our plastic crisis stems heavily from the limitations of the recycling technology we use, as well as the materials our plastics are made of. According to the EPA, less than 10 percent of plastic discarded in the United States in 2018 was recycled. And of the seven types of conventional plastics currently enumerated in the resin identification label (the chasing-arrows icon stamped on our products), only two are actually recyclable. Even those lose so much of their quality in the process that they can rarely be recycled more than once.

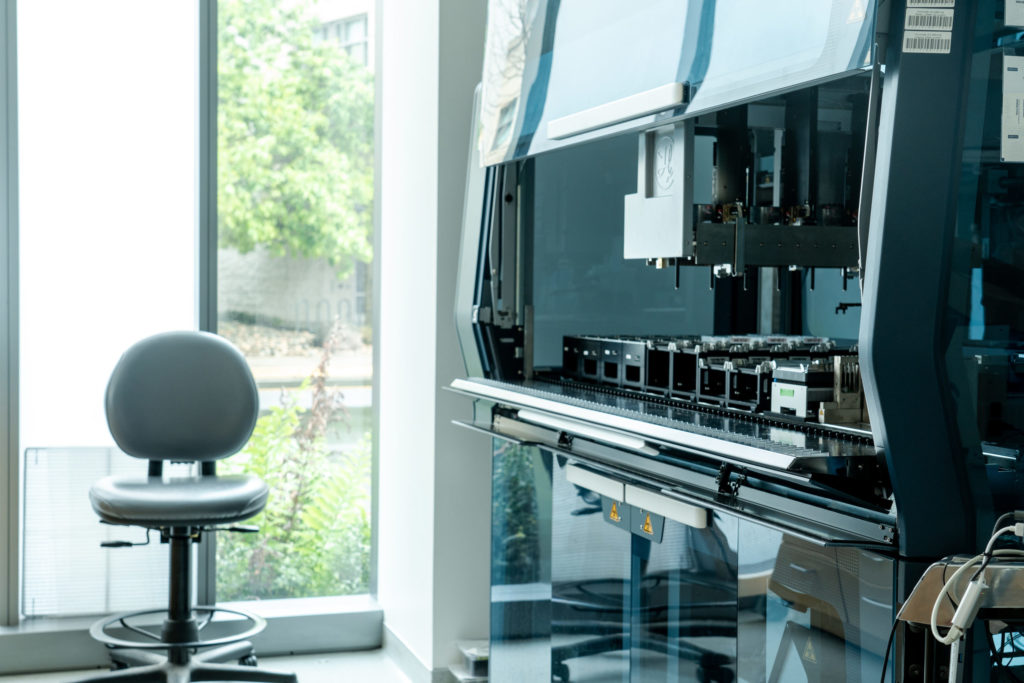

Enter poly(diketoenamine), or PDK, a new material that promises to be endlessly recyclable. The breakthrough discovery came in 2017, when a team of scientists at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory led by Brett Helms, Ph.D. ’06, noticed, while cleaning glassware, that PDK broke down to a snow globe-like flurry of dispersed solids, depolymerizing back to its original monomers, the basic building blocks of plastic. The process, known as chemical recycling, had produced monomers that were good as new and could be re-polymerized into new material with no loss in quality.

While the team enthusiastically announced the new material in 2019, major questions over the costs and logistics of introducing PDKs to the market remained.

In April, a team led by Helms, Corinne Scown, Ph.D. ’10, Jay Keasling, and Kristin Persson published a study demonstrating how PDK plastics could be produced at scale and made commercially viable. For now, the ideal application for PDK is manufacturing, where material can be reclaimed and recycled without passing through a conventional sorting facility. Think large products like furniture and automotive parts. But Helms hopes to see consumer products, such as shoes and glasses frames, being made from PDK in the near future.

Another alternative to traditional petroleum-based plastic are biodegradable materials. But they have two major problems. First, they are often indistinguishable from single-use plastics and, if not properly sorted, can contaminate recyclable plastics. Also, it can take months for the material to decompose in industrial-scale composting facilities. Even decomposed, biodegradables can form microplastics that contaminate the ocean and infiltrate the food chain.

In the end, Scown says, “reducing consumption is one of the most powerful tools we have.

Better biodegradables are on the way, however. A new process developed by Berkeley scientists uses a polyester-eating enzyme to break down plastics quickly in a standard compost bin. An April study co-authored by Ting Xu and Scown showed how, in a matter of days or weeks, heat, soil, and water successfully release the enzymes, which are trapped in the polymer at room temperature. These enzymes reduce the plastic to monomers, which soil microbes then feed on. Not only is the process fast and inexpensive, it also eliminates microplastics.

Still, challenges remain. Organic farmers, for example, “are not technically allowed to use compost that includes compostable plastics, no matter how thoroughly they have broken down,” Scown explains. She adds that, ultimately, “there is no silver bullet to solving the plastic waste crisis; because plastics are used for different applications, all with different properties, it would be nearly impossible to develop one special polymer that works for everything.”

In the end, she says, “reducing consumption is one of the most powerful tools we have.”