A man of the campus

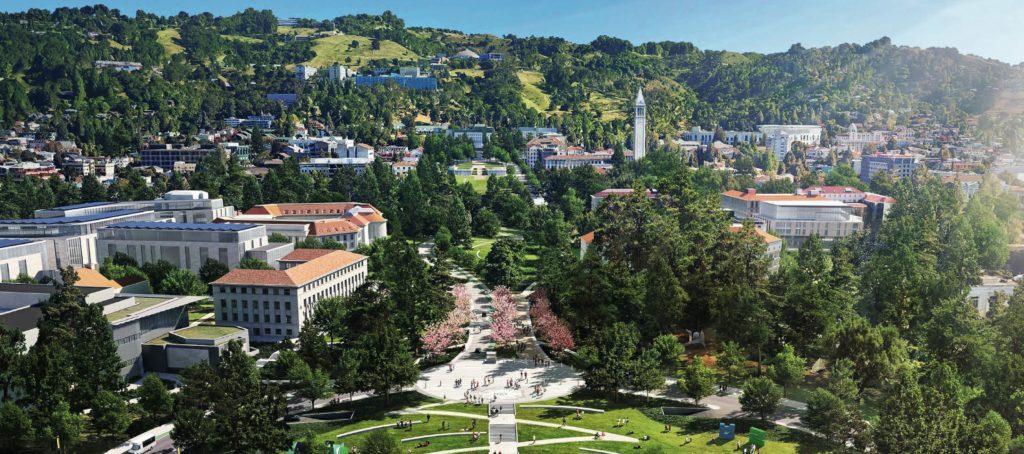

Karl Pister’s sublime Berkeley moment arrives often and like an expected guest when he mounts the stepped bridge spanning the south fork of Strawberry Creek and crosses into Faculty Glade. There, on the pitched grass bowl that once hosted Ohlone campers, time defers to him. There, he keeps an appointment with an enduring family memory and an indelible sense of place.

“Its incredible beauty hasn’t changed in the 50-plus years I’ve been around here,” says CAA’s 2006 Alumnus of the Year. “Every time I come up on the glade, I get this connection to a very vivid memory of visiting Tuolumne Meadows in Yosemite as a child and then taking my own family there year after year. The unchanged majestic beauty of both places gives me a jolt of reassurance.”

The words of an aesthete might sound anomalous when matched against a nine-page, single-spaced résumé listing his 20 academic titles, his university and community awards, and his achievements in the engineering world of concrete and rebar. But, in fact, Karl S. Pister, B.S. civil engineering ’45; M.S. civil engineering ’48; Ph.D. theoretical and applied mechanics, University of Illinois ’52; professor of civil engineering at Cal; dean of the College of Engineering for ten years; and chancellor at the University of California, Santa Cruz for six years; entered Cal in 1942 as a “terribly intimidated,” bookish 17-year-old farm boy from Stockton who had been told by counselors that he had an aptitude for English literature. He even struggled to avoid flunking his first Berkeley math course.

It was then, on the precipice of experiencing failure for the first time, that the high school valedictorian and California Scholarship Federation Award winner decided to apply himself. More than 60 years later, even in retirement, he is still applying himself to the benefit of the Cal community and the world of engineering and education.

“It is hard to find an individual whose life’s work better mirrors the very mission of our university,” says Chancellor Robert Birgeneu, the latest in the line of 10 chancellors Pister has served. “Teaching, researching, and service define Karl Pister. Karl’s deep understanding of the Berkeley campus and of the workings of the UC system have been invaluable to me. Most recently, he has led the complex planning effort for the renaissance of the southeast area of the campus, including the stadium master plan and the new law and business building.”

That Pister was chosen to head a 30-member panel to oversee reconstruction and upgrading of Boalt Hall School of Law, the Haas School of Business, 82-year-old Memorial Stadium, and their common areas—the most ambitious campus project in decades—surprises no one, because the plan combines gargantuan engineering challenges with the need for skillful political diplomacy. Building durable structures and building political constituencies from competing interests are Pister’s hallmarks.

He is eminently cordial and composed, his focus direct, his sentences structured and circumspect with a measured precision. He balances himself on a low center of gravity, something engineers strive for in tall buildings, particularly ones erected in seismic areas. He is the silver-haired sort you would send into challenging situations—say rebuilding New Orleans or Iraq.

From 1978–80 Pister served as vice chairman and chairman of the nine-campus Academic Council and Assembly of the Academic Senate while also serving as faculty representative to the Board of Regents. From 1980–90, despite initially asking that his name be removed from the list of prospects to be dean of the College of Engineering and after being overridden, he served as dean for 10 years. During his tenure, the school emerged as one of the highest-regarded programs in the nation. In 1990 UC President David Gardner asked him to serve as interim chancellor of UC Santa Cruz, a campus that Gardner described as being in such chaos that a permanent chancellor could not be recruited.

Pister can still recall his first impression of the 2,000-acre forested campus with 10,000 students. “There’s no Campanile. There’s no tower. Where’s the campus? There’s no there there.”

What was there in the spring of 1991, when Pister and his wife, Rita, arrived, was seething turmoil. A civil war was brewing. Budget cuts were causing retrenchments, and battle lines were forming over prioritizing teaching over research. Within the woodsy surroundings, townsfolk and members of the campus community were also seething over what they believed were ad hoc plans to expand the university from eight colleges to ten.

“This meant cutting down 150 trees in an area known as ‘Elf Land,'” says Pister, referring to a secluded, forested acre favored by students, townsfolk, and ramblers practicing “alternative behaviors,” as Pister would be prone to say. “We had intruders who got in the way of logging. Forty-four people ended up being arrested. It was an uncomfortable affair.”

The local press treated him skeptically. His own faculty verbally assaulted him. His wife was falsely accused of recklessly spending $10,000 on tableware. Garbage was dumped on his campus household doorstep. Even his life was threatened. He had to have a security escort wherever he went on campus.

“As a dean, I never had this kind of problem,” he remembers when interviewed. But he also remembered his own sense of place more than 25 years earlier as a young, bearded, in his words “dean-and-chancellor-bashing faculty member” upset with the UC administration’s “mishandling” of the Free Speech Movement. At UC Santa Cruz, Pister sought and got input from faculty, students, staff, and administrative officers on budget allocations. “We basically put the entire campus budget out into the public,” he says. He invited members of the public to express their views on campus expansion, even offering to reconsider disputed plans for extending a thoroughfare through the campus’s Great Meadow. “I took walks down and back up again,” Pister told an interviewer. “I said there is no way that I’m going to be the one that wrecks the meadow.”

Within a year, according to Rita Pister, who has been married to Karl for 55 years, “We were being welcomed, and we were making friends.” While Elf Land was sacrificed for new building facilities, Pister clarified parameters for developing other campus land and, with input from the community, established a long-range development plan that drew praise both on and off campus. Stability had been restored. And through Pister-initiated upgrades of undergraduate teaching standards and his outreach programs, including the now-renowned Monterey Bay Educational Consortium and the Monterey Bay Science and Technology Center, UC Santa Cruz regained its footing and its prominence. All this did not go unnoticed up north. Within a year Pister was named permanent chancellor, a post he held until 1996 when he announced his intention to retire. Not missing a beat, newly elected UC President Richard Atkinson appointed him senior associate to the president responsible for broadening Cal’s outreach and improving education opportunities for underrepresented students.

Characteristically, Karl Pister applied himself at his new position. Through his advocacy, the state budget for university outreach nearly tripled from $61.7 million in 1996 to $178.5 million four years later.

“He continues to be at the center of meeting critical challenges for education,” Executive Vice Chancellor and Provost Paul R. Gray, himself a former engineering dean, said in a letter nominating Pister for Alumnus of the Year. Noting that 20 letters of support for Pister accompanied his nomination, Gray said, “There may be nominees for this award with more fame, but I am certain there are none with more substance.”

Karl Pister was born in 1925, the older of two brothers raised in a 14-room Victorian house on 320 acres in Stockton that had been in his mother’s family since the mid-19th century. He remembers having the run of the land. He remembers his mother calling him and his younger brother Phil “country boys,” a term that was not pejorative but meant to imbue the two boys with a sense of pride built on practical wisdom.

The summer before entering Berkeley, Pister worked on a surveying party for the Division of Highways, a precursor of Caltrans. The job was to plan a new highway between Vallejo and the arsenal at Benicia. The lead surveyor tutored Pister, helping him master and enjoy the mathematics and implementation of the surveying equipment. Pister also realized how much he had come to enjoy being paid to work outdoors. He decided to become a civil engineer. “You don’t have to sit at a desk,” he says. “That shows you how superficial experiences can influence a career choice. That happens in everyday life.”

But everyday student life became a struggle for the 17-year-old “country boy.” The move from a rural farmhouse to a boarding house on Hearst Avenue, newfound freedom, and urban distractions combined to knock young Karl off course. “I wasn’t educationally disadvantaged. It was cultural shock,” he says in his biography. “When I think of Chicano students and African-American or Native-American students coming here as the first generation to go to college, I can see very strong parallels.”

This was a lesson Pister would remember his entire career. Whether as a teacher or administrator, he retained empathy for students arriving with cultural disadvantages. He sought them out and encouraged Berkeley to do likewise on a large scale. Outreach and inclusion defined him and, in turn, he helped define the current university.

“He is gracious, brilliant, and considerate. He could have the most enormous ego, but he has an incredible sense of humility,” says CAA President Debbie Cole ’72. “His concern for undergraduate and graduate alumni making their connections back to the University and enabling them to make those connections has been incredibly valuable. He’s an unusual engineer in that he’s capable of having discussions about many things. He improves the quality of any room he’s in.”

The accolades and list of accomplishments grow even as Pister continues to serve the university community he’s been a member of virtually his whole adult life, with two exceptions—when he served as a naval officer in the Pacific at the end of World War II and when he earned his Ph.D. at the University of Illinois.

“As an engineer, leader, administrator, and even in retirement he’s done way more than his share of service,” observes CAA Executive Director Randall Parent ’77. “He has made himself available as a mentor and friend to alums, students, and to the whole university. And we’re still calling on him.”

Two years ago, in a speech while being honored following the completion of the 637-page oral history of his life, Pister reflected succinctly and with characteristic humility on his own career. “One of the most shocking realizations that came out of this history is the complete absence of any strategic plan for my life. My life evolved much like the Berkeley campus has evolved—in a very satisfactory way without much need for planning.”

And yet, he is able to contradict himself with ease. “An engineer is different. Engineering gives you a structure. You think in a straightforward, linear fashion from alpha to omega. You gather information. You find the best solutions.”

But when asked about his greatest engineering accomplishments, he demurs, saying: “I have always believed that the development of people is more important than developing things. I take more pride in my students than in the research papers we produced.”

It is more or less a straight line—south, southeast, as the crow flies—from Karl Pister’s office on the seventh floor of Davis Hall to the Faculty Club where he enjoys having lunch with colleagues, many of them former students, including 32 doctoral students he fostered. Sometimes he stops by Cory Hall, which stands adjacent to his own building, to visit with his son Kristofer, M.S. electrical engineering ’89, Ph.D. electrical engineering ’92, and now an engineering professor working on a wireless sensor network.

“We’ve had 42 years of interaction,” says the younger Pister, one of six siblings, who collectively have earned one doctorate, two master’s, two bachelor’s, and three teaching credentials from Berkeley. “I think I’ve been to five retirement dinners for him, and he’s still here. Whenever there are toasts in his honor, you hear the same word over and over—’integrity.'”

With his son, a colleague, or alone, Pister relishes his walk to Faculty Glade. “When I walk on familiar paths that I have followed on countless occasions, I find it difficult to accept that it is more than 60 years since I was first here. The splendor continues to trigger the same emotional response. My love affair with Cal has not diminished in its intensity. It has shaped my life and that of my family.”

Patrick Dillon is executive editor of California magazine. Portions of this profile have been drawn from the oral history of Karl Pister, property of the Bancroft Library.

From the January February 2006 Chinafornia issue of California.