Brain/machine interface

In Spiderman 2, mild-mannered physicist Dr. Otto Octavius attaches four mechanical limbs to his own spinal cord to conduct nuclear energy experiments. Octavius manipulates the four superhuman limbs with his mind through a clever brain/machine interface. But after a radiation test goes bad, his computerized limbs compel him to do terrible deeds. He becomes the evil Dr. Octopus.

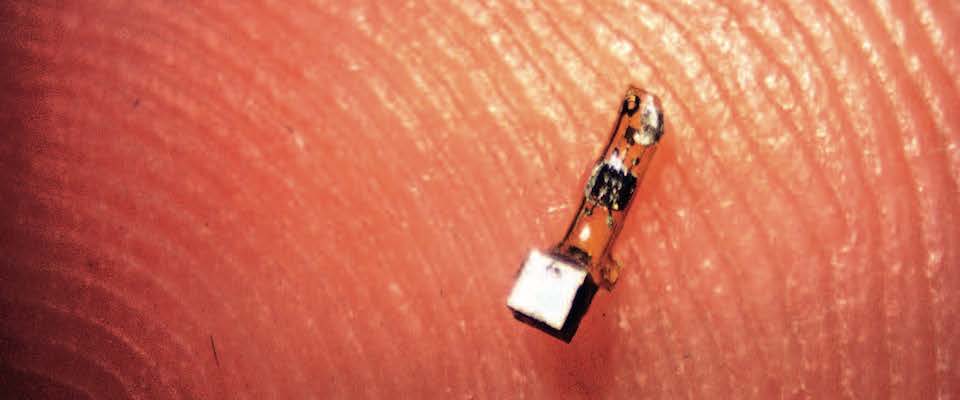

For moviegoers, Dr. Octopus is mere fantasy. For Jose Carmena, he is an inspiration. An assistant professor at the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences, Carmena is developing his own brain/machine interfaces, or BMIs. But he hopes to use them for good, not evil.

As early as 2003, while a postdoctorate at Duke University, Carmena was thrust into the national spotlight when his team built the first BMI that allowed primates to control a robotic arm with only their thoughts. Two years later, the same team was able to show that the subjects’ brain structures adapted to treat the mechanical arm as if it were their own appendage.

To improve the quality of life for people with motor disabilities, Carmena is working to give users a sense of where the limb is relative to the rest of the body. “The ultimate BMI system will be a trade-off between neural and artificial commands,” Carmena says. “Just think about it. Do you expect to have a prosthetic arm controlled purely by brain signals? For example, how would you prevent the arm from moving to undesired places when you are not paying attention?”