Following migrants deep into Chiapas, the author discovers the ghost of her Jewish abuelito.

We were abusing our little Mexican rental car by clattering vigorously up a potholed road in southern Chiapas, where somebody had told us to get breakfast at a place called the Casa Grande. Around us stretched the coffee plantations, which were deep green and luminous and looked as though they had been poured down the slope of the great volcano, Tacaná. There were orchids, tangles of bougainvillea, flashes of white whenever large birds rose and took wing. “Where the hell is this Casa Grande?” asked Germán Romero, who was driving. Germán is Mexican but spent a year in Wisconsin during high school and learned excellent idiomatic English. He hairpinned left, sighed, and kept climbing.

The state of Chiapas is nearly the size and shape of South Carolina, with a long, zigzag southeastern border that separates Mexico from Guatemala. Various places in Chiapas attract foreign visitors by the busload: Palenque, in the north, which has Mayan temples in the jungle; San Cristóbal de Las Casas, in the central highlands, which has narrow colonial streets and exquisite mountain light. This was not one of those places. We were 20 miles from the city of Tapachula, where my hotel room had an outdoor clothesline, a rattling air conditioner, and wall lizards. I liked Tapachula because the narrow downtown sidewalks were full of bustling teenagers and businessmen striding along holding cell phones to their ears, and there was a big public pool where for 50 cents I could hang my towel over a rusty nail and swim laps in water that chemicals had turned the color of Windex. Every time I came back from the pool, Germán and my other co-worker, American photographer Alex Webb, observed me briefly to check for rashes and then went back to their laptops.

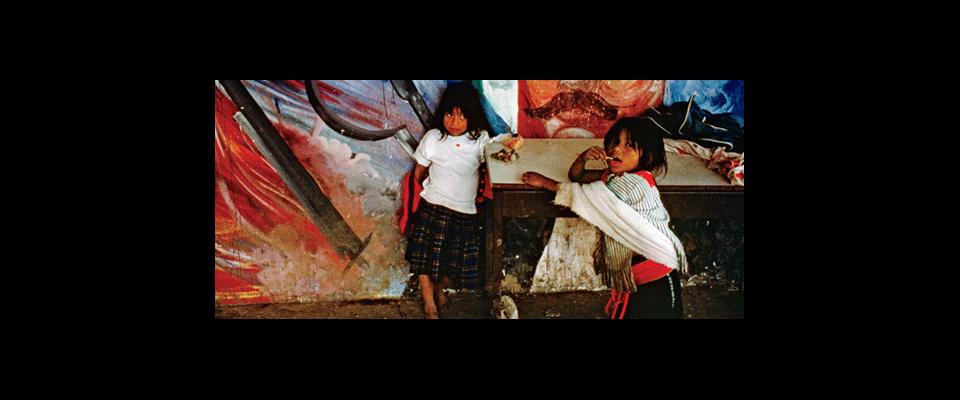

Alex gets up at dawn when he’s working, and on this particular morning he and Germán had shoveled me out of the hotel at first light so we could drive to the Tacaná coffee country to find migrants harvesting the beans. We were interviewing and photographing along the southern Mexico border, where the thick daily drama is the northward-bound crossing of undocumented Central Americans. Most are passing through Mexico en route to the United States, but here in the plantations beneath the top of the volcano, Guatemalans arrive on foot at the beginning of every harvest season, having traversed the mountain on narrow dirt paths; they stay long enough to earn Mexican pesos, then return home. Already in the early-morning hours we had stopped the car twice at the end of dirt roads to climb out and trace a few of those footpaths, following the glint of machetes as groups of coffee workers hurried ahead of us into the growth. The plantings were as tangled and random as live oak along an untended California hillside. The air was damp. “Buzzing and butterflies,” I had written into my notes. “Two young teenage sisters, indigenous, speak Mamean, no Spanish. Older sister maybe 4’10”, long blue skirt, black hair gathered in silver barrette, reaches up, bends a huge tree limb down with one hand so she can strip beans from it with the other.”

My notebooks were filling with these people—migrants, outsiders, men and women propelled into exile, temporarily or permanently, by the need to find paying work. In southern Chiapas the story was older and richer than I had understood before I came; in Tapachula we had met not only Hondurans and Guatemalans and El Salvadorans and Nicaraguans, but also Chinese Mexicans and Japanese Mexicans, the grandchildren of agricultural workers who came to Chiapas in the early 1900s and stayed. I had met coffee growers with German surnames, their own grandparents the founders of the turn-of-the-century Chiapas plantations for the beans that were then becoming so popular in Europe. The Casa Grande, in fact, had been constructed as a plantation house by a family named Braun. Then the grounds it had been built on were nationalized during World War II and Herr/Señor Braun went back to Germany. The house fell into disrepair and finally some local businessmen decided to renovate it into a restaurant.

Germán peered at a small road sign with an arrow. “OK, I think here,” he said, and turned in toward a driveway in the trees. A long sweep of lawn opened out before us. At the far end of the lawn, set off not by coffee trees but by tropical landscaping forming a walkway, stood a three-story balconied edifice of burnished wood and stone, with gables and porticos and columns and dormer windows and a complicated, pointed roof that made the whole building loom above the grounds like a massive pagoda. I swore appreciatively in Spanish. Germán swore appreciatively in English. Alex hefted a couple of his cameras and we went in to get some food.

The breakfast tables were outside, on the wide veranda that wrapped the house. I ordered huevos rancheros and went walking, to stretch my legs. I admired the view. I studied the stained-glass panel above the front doorway, which contained in ornate lettering the date of the Casa Grande’s completion: 1929. And then I understood, all at once, that 75 years ago my grandfather must have pulled the Model A truck up this driveway and stood just here, on this veranda, holding his hat, waiting to sell the plantation owner some aspirin.

In my family my grandfather was called Abuelito, which is Spanish for “grandpa.” He was a Polish Jew. He had married my grandmother in Warsaw, and because post–World War I Poland was a place that loathed Jews, Abuelito had boarded a freighter in 1924, when he was as old as the century—24, the same age my son is now. Abuelito crossed the Atlantic and landed in Mexico, where, a family friend who had already made the journey had told him, a European Jew could prosper in the sunshine while waiting for the final passage north into the United States. Abuelito worked as an electrician for a while, because he knew how to do that; my father says Abuelito helped install the lights in the National Palace in Mexico City. He sent for his young wife—that would be Abuelita, who used to tell me stories about stepping off the ship at Veracruz, carrying her belongings in one hand, and seeing palm trees and blue sky and sailors at attention in their shining white uniforms. The Abuelitos raised my father and his sister as trilingual Mexicans; the children spoke Spanish in the house, attended elementary school classes in English, listened to their parents fight with each other in Polish. When Abuelito took a job with the Bayer company, selling aspirin all over the Mexican countryside, the trucks had cafiaspirina painted in big letters across the side. There was caffeine in the aspirin; Bayer wanted the Mexicans to know that. “Para dolores de cabeza, tome cafiaspirina,” my father says the billboards read. “For headaches, take our aspirin.” His sales territory stretched the length of Mexico, including Chiapas; one of my favorite Abuelito photographs is of him somewhere in the southern Mexican jungle, exasperated, watching three men try to pry the rear tires out of a deep pool of mud.

Up the volcano road he would have come, then, jouncing in the cafiaspirina truck. Down in town, in Tapachula or in the slopeside coffee village of Unión Juárez, they would have seen him approaching—he was a handsome man, blond, blue-eyed, his Spanish correct but guttural, with the Polish accent. Buenos días, they would have said. Surely you are looking for the other European man. And they would have sent him on his way, up to the Casa Grande, so that he and Herr Braun could stand on the beautiful wooden veranda and gaze at each other. It would have been the 1930s by that time; did they talk about what was coming? Had Braun read Mein Kampf? Did Abuelito remember his German clearly enough to make pleasantries before the sale, perhaps step inside at Braun’s invitation and sip coffee from a china cup? Or did he remain on the veranda, speaking stiffly in Spanish, recalling during the transaction the wording of the most recent anguished letters he and my grandmother had written to Warsaw, imploring her sisters to get out while they could?

The sisters died in the ghetto or at Auschwitz; the records are poor, and no one knows precisely. We are alive—my father, my Mexicanraised cousins, my brothers, my children, and me—because the Abuelitos left. At the Casa Grande I walked the circumference of the house, my hand on the porch rail, studying the polished wood the way I supposed Abuelito would have studied it; some of the lumber had been shipped from Europe, we were told, and some carried up from the local forests to give the balconies the elegance the Germans desired.

Abuelito was 70 by the time he finally left Mexico, to be near the family his son was raising in California. He spoke his final words in Spanish and in Yiddish, in a hospital in San Francisco, and now in Chiapas I imagined introducing Abuelito’s ghost to the two Nicaraguan boys I had met a few days earlier at the migrants’ refugee center in Tapachula. The boys were washing dishes when I met them, as their mothers had taught them to do. They had just crossed one border illegally and were preparing themselves for the next. Perhaps they would go to California, they said, and they puffed up their chests and snapped each other with dishrags.

Abuelito was not a broad-minded man; it took him a long time to warm to my mother, because she was neither Mexican nor Jewish. He would have called the Nicaraguan boys peones, I think. He would have reminded me that when he and Abuelita crossed into the United States, they did so with documents; that his son had served in the American navy; that I had been with Abuelito in San Francisco the day he passed his own American citizenship examination, a dignified old man in a good dark suit, trying to remember whether the national anthem had been composed by Francis Scott Key or Betsy Ross. He would have patted me on the head, the way he did that day, murmuring to me in three languages—”Good koppela, chula.” “Good little head, my pretty one.” And I believe he would have declined to understand what I could possibly mean when I said: Abuelito, these Nicaraguan boys? And the Salvadoran couple with the 6-month-old baby? And the two gay Honduran men, and the woman who started to cry when she told me she would be sending her American earnings back to Guatemala, for the three children she left behind? They’re scared. They’re driven. They’re desperate for something better. All of them look like you.