With or without Castro, Cuba’s revolt won’t stop.

Ronald Reagan was preparing an invasion that was going to rescue the whole island next week. Fidel was about to be airlifted to a new home in Miami, the guest of his secret patrons and supporters, the U.S. government. The soldiers were already lining up for Bay of Pigs II, and a new constitution had been drawn up for the island that was going to emerge tomorrow. There was a shortage of everything except rumors—wild and impossible imaginings, crazy stories and flights of inspired imagination—the first time I set foot in Havana, in the spring of 1987, and the only thing I could be sure of was that none of it was likely to come true.

I was walking down streets called Virtues and Solitude, Hope and Liberation, toward a capitol building that was a perfect replica of the one I had just seen in Washington, D.C. (though, Cuban friends assured me, a little bit larger). I had flown into José Martí International Airport, named in honor of the Cuban revolutionary and exile whom Fidel Castro had made his alter ego and official hero—even as the Cuban exiles and passionate Castro haters in Florida also claimed him as their hero, a fighter for an independent Cuba while exiled in America. Three months later I would be standing with a large crowd in the tiny town of Artemisa while a torrential midsummer rain drenched us all and, at the far end of a soggy field, a bearded man in fatigues talked and talked in a lucid, forceful Spanish that even a 5-year-old (or a visiting journalist from Time magazine, myself ) could follow. Castro had already been president for 28 years at that point, and across the waters all his enemies were convinced that he was ready to give out at any moment (his own people, many of whom had never known another leader, mostly seemed to believe that he would never die, any more than a bad dream or vision dies).

The only visitors I saw then, along the tropical, yawning, carless streets, in the Mafia-built hotels still creaky with hand-operated elevators, along the seawall where kids sat looking out toward America 90 miles away, were eager Bulgarians, North Koreans traveling in pairs, like missionaries, and Soviets who kissed their fingers and thanked the heavens they didn’t believe in as they watched near-naked dancers sashay past during Carnaval (rescheduled by the Revolution to coincide not with the Christian period of austerity but with the anniversary of Fidel’s first strike, on the Moncada barracks, in late July 1953, and a different kind of quasi-religious privation). And when, four years later, the Soviet bloc collapsed and even those visitors and supporters fell away, a “special period” began, which meant that I found even more of nothing in the Cuban shops, and the Soviet-sponsored bare shelves were replaced by Soviet-deserted bare shelves. More books came churning out: Castro’s Final Hour, Cuba the Morning After. The island of waiting was on the brink of transformation.

Fifteen years on, the stories are still the same, even though the evergreen Cuban leader, now 80, really does at last seem to be saying his good-byes. By now, however, he has already survived ten U.S. presidents, outlasted more than three dozen assassination attempts (by some counts), and endured the hundred-millionth rumor of his impending demise.

The story of Fidel’s reign is as paradoxical as that of any revolutionary, bearing out the uneasy global truth that every son turns into the father he rebels against. Castro came to power to rescue his island from the tyranny of the dollar and widespread prostitution and has somehow, after decades on his throne, turned his island into a place where the governing obsession is the dollar and prostitution is everywhere. His main ally in all this is, perversely, a Washington that, by maintaining an economic blockade on the tiny island, allows Castro to present himself as a genuine David standing up to Goliath and a lone voice of independence who is an inspiration to revolutionaries everywhere. The beauty of Cuba is the complication of Cuba, a tragic place of infectious effervescence where fading buildings that are collapsing and filled with nothing but dust are lit up with an energy, a vitality, even at times an ebullience, like nowhere else I have seen in a lifetime of traveling.

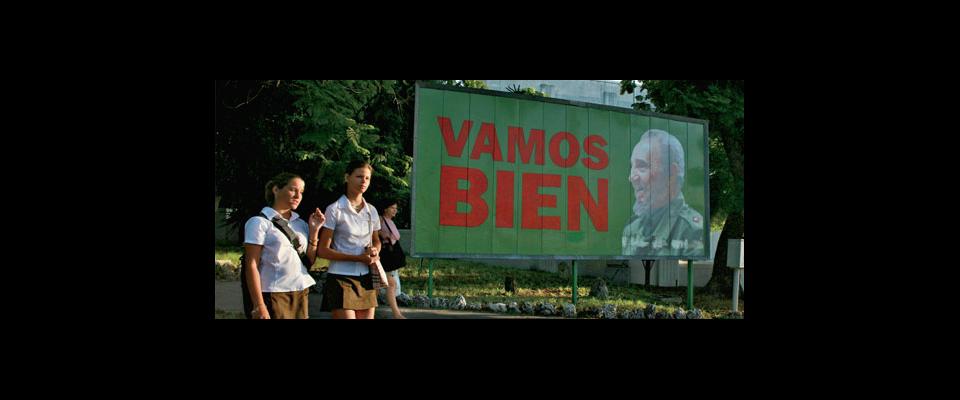

Imagine Brazil compressed into a small, clawlike island with fewer people than Greater Mexico City. Picture New Orleans reborn with an African beat and European intellectuals, so that you can hear drums beating from every park as darkness falls, while inside the bare rooms the kids you meet are as definitive on Franco and Camus as they are on Shakira and Oliver Stone. When you land at the airport at two in the morning and walk out onto the long, jungly roads, with nothing but huge billboards—empty promises—hovering above you, you can still feel a buzz, a spirit, an intoxication in the air that makes you really feel that, as the billboards weirdly say, it is always the 26th of July (1953).

Nearly all the figures you are likely to meet in Cuba are, of course, the ones most drawn to foreigners, desperate to get out; the ones who have spent their entire lives hating Castro, as restless teenagers will hate the puritanical father who grounds them for the next 48 years. Yet even they, in my experience, will always assure you that their leader is brilliant, supple, and craftier than any other character on the global stage. He has turned their specklike homeland into a major international player, and he has created excellent doctors (albeit they have no aspirin to give out) and wonderful schools (with no textbooks on offer). The only thing worse than having Fidel in power, they sometimes tell you, is having anyone else. If he is succeeded by his younger brother, Raúl, Cuba will suffer under an even more oppressive tyranny run by a man as brutal as Fidel—perhaps more so—but with little of his fire or intelligence. If the country is taken over by the exiles from Florida, who have been redecorating for 50 years an island that no longer exists, it will become disfigured in a different direction. Never has “better the devil you know” had a keener or more anguished implication.

And in the middle of all these nervous complaints, guitars are being strummed along the beautiful Malecón, the corniche that stretches its arm around the fading tropi-colored buildings of Central Havana, and girls are asking you to marry them to get them out, while an old man requests pictures of Jackie Robinson and Ava Gardner. In the absence of almost everything, people fill the emptiness with sex, with music, with flamboyant embroideries. All the time that they are supposed to be working for the government, they are busy working around it, keeping the island afloat somehow through sheer resourcefulness and determination and genuine, unscripted compañero-ship alone. The party subverts the Party at every turn.

It is presumptuous, I know, to speak of a country and a predicament not my own, and I leave to political pundits the job of telling us that Cuba is a sometime socialist utopia and longtime repressive hell. For me it has always been, more than anything, a human place, and even after six eventful trips there I find that I have seldom seen people so disenchanted, so passionate, so engaged in all the possibilities of every moment (because so exiled from the chance to change anything deep down). Strangers ask you for jobs with the CIA, or offer you jobs with the Cuban CIA. A kind man with watery eyes approaches you in the cathedral and asks if you will take a letter to his mother in the United States (I did so, and only just before sending it, looked inside to find that it was in fact addressed to a desk officer at the State Department). Everything is permanently dancing and shifting, and nothing is going anywhere at all.

Like almost every foreign visitor who has set foot on the island, from Christopher Columbus to Thomas Merton, and from Graham Greene to yesterday’s bedazzled new fiancé, I fell almost instantly under the island’s spell the moment I arrived. Perhaps what I really fell in love with was a unique mix of vibrancy and ambiguity. The day I returned from my first trip, I went to my travel agent in Santa Barbara and bought another ticket, to go down a few weeks later (through Merida, Mexico, and in years to come, I would go through Canada). Going to Cuba became my annual way to remind myself of what stood (and slouched and shimmied) outside abstractions and ideologies, a political and emotional and moral conundrum that asks you what you will do with smiling new friends who say they are happy to be thrown into prison because they can get food there, and with relics of the American Empire that preserve old American dreams more lovingly than anything in America does.

My very first morning in Havana, as I surveyed a futuristic building along the once-modern boulevard of La Rampa, stranded there now like a crumpled IOU, a Cuban with Chinese features leaned in and whispered a hello (he could tell I was a visitor, despite my scruffy clothes and dark complexion, by the fact I was looking at the ghostly showpiece). Minutes later I was following Carlos into a cavernous, dusty apartment in Central Havana, being introduced to “brothers” who looked less like him than I did and then bumping back across town to his two-room apartment on a rooftop in the Vedado district. Kids were conducting heated conversations on Michael Jackson’s skin color, a rooster (called Reagan in honor of his speech patterns) was strutting about calling reveille, a boom box was blasting Madonna’s “Like a Virgin,” and Carlos was asking me what I really thought of William Saroyan and whether Spinoza had it over Leibniz.

Twenty minutes later, he was asking me if I wouldn’t mind giving him my passport so he could go off to the land he’d been dreaming of for all his 35 years. It was a variation of the appeal I heard from almost every Cuban I met—better the reality you don’t know, in this case, than the one you do—and four or five visits later, I did at last help Carlos escape, as a political refugee (and without parting with my passport), to America. So quick-witted and enterprising and sophisticated a spirit could only flourish, I knew, in the Land of Opportunity. Yet when he touched down in New York, and later in Miami, Carlos saw drug dealers for the first time, and homeless people, and gangs. In America you can do anything, he told his friends back home in Havana, but you can also be nothing, with no family or community or overarching vision to hold you up or to rebel against. You’re better off, he told them, to their shock and disappointment, in the Havana that you know.

Cuba was—still is—a cluster of sunlit streets with shadows everywhere. It is a proudly patriotic island that, like nowhere else in the Americas, draws Madrid and West Africa and the Antilles together, so you are seeing Truffaut while talking of the Mets, with Yoruba deities being placated in one corner. It is as physically beautiful a place as exists on earth, it wins more gold medals per capita at every Olympics than any other nation, and it is famous for its oppressions and the hatreds it inspires, an intense family dispute that has been going on now for half a century or more.

As the hundred-millionth rumor of his departure hisses across the Central Havana rooftops, Castro himself appears to be giving way to something even more chaotic and repressive, thanks to those who have hated him, or followed him, for longer than is healthy. But the Cuba that I, and more and more Americans, know seems unlikely to follow any script, except insofar as it can jeer at it and riff on it and embellish it with the confidence that little on this loose-limbed island listens to either 19th-century German philosophers or 21st-century American potentates. Cuba is the home of a permanent revolution against all the ideas we have of it.

From the July August 2007 Summer Travel Issue issue of California.