Chile recalls the life I thought I wanted.

I once imagined starting my life as a world traveler in Chile. I was in college then. Vietnam was climaxing beyond my comprehension—so much bigger than I was, a girl without brothers. It was a time of portentous possibilities in Latin America, both good and horrific, and I wanted to be on the ground to see history unfold in a language I could understand. I had discovered the poetry of Pablo Neruda; even now I can hear in my head certain lines in the accent of a Castilian reader from a recording given to me by my college roommate. Neruda wrote about love and the earth, about change and perseverance in a country of powerful rivers and aching winds. I dreamed of driving through his long and narrow Chile, precarious as a pleat on the skirt of the Andes, until I reached the end of the earth. And there, at 21, I would begin my life as an adult.

Things didn’t work out that way. Three decades intervened. I went on to become a journalist, covering El Salvador and Mexico as well as my own country, and more recently to research books about Iraq, Colombia, and China. I never stopped talking about Chile and following it, in my way, but traveling there slipped down my list of personal priorities.

Then, six months ago, my daughter, Elizabeth, called from college to say she had decided to do her semester abroad in Chile, instead of England as originally planned. Her program had a month built in for travel, and she wanted to divide it between hotels with us and hostels with friends in Peru and Bolivia. Would we come? I felt a rush of excitement. I was going back to Chile. My husband, Henry, had only one request. Since we didn’t know when we’d get back to South America, could we stop in Buenos Aires on the way?

We loved Buenos Aires: a come-hither city of European architecture and Mediterranean cafés I found so beguiling I fantasized about living there someday. We wandered San Telmo’s Sunday bazaar with its tango dancers and street vendors carrying trays of warm empanadas, we toured the famous Recoleta cemetery where Eva Peron’s body had finally been entombed after much posthumous drama, we ate moderately priced bifsteks with little paper cows stuck in them designating doneness, and we found ourselves on a plane looking beyond the flat Argentine pampas to the stern serrated peaks of the Andes.

My first glimpse of Santiago was of an inland city nestled in smog. Driving in from the airport past a polluted stream that gave no hint of the spectacular rivers we would see later, we entered a busy city center of offices and apartments with leafy streets leading up the mountainside, like arteries away from the heart, to lavish suburban developments, often ending in multistory malls people referred to as “el shopping.” Latin America’s most stable economy was evident, and so were its costs: the sidewalk cafés that were mostly chains; the suburban model houses that looked like an American child’s drawing, only barely larger than playhouses; a middle class unable to afford the Chile we were about to see. Elizabeth loved her host family and her program but wished aloud that the workaday Santiago felt more like Buenos Aires.

“Why was it you wanted to come here again?” she asked over sandwiches heavy on mayonnaise.

A child’s simple why question. I didn’t know how to answer it. I was just a year older than Elizabeth was now when I first thought of coming here.

“I can’t remember exactly,” I finally said. She and Henry stared at me, then at each other, and burst out laughing. For 30 years I had wanted to come here and I didn’t know why?

Later, a scene came to mind I had all but forgotten: a panel of Fulbright fellowship judges lined up behind a table covered with a white cloth in a San Francisco hotel room, me sitting before them on a folding chair as they grilled me about hectares of export crops and Chilean splinter groups. With no clear career path and no foreseeable income, I had done what any resourceful English-Spanish major with a history minor would do: submit a fellowship proposal to study Neruda’s use of synesthetic metaphor during the regime of the world’s first democratically elected Socialist president, Chile’s Salvador Allende. The judges saw through my academic concoction, I was certain of it. I remember flying back to Los Angeles dejected, staring at the airline hostesses’ mod pink-and-orange miniskirts, envying their travel perks, and finding meaning for the first time in the content-free valedictory speech I’d given in high school on my assigned topic, “The Road Not Taken.”

But my rejection letter came with an unexpected consolation prize that ultimately brought me here: a grant to do graduate work at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. It was one of those perfect little circles life draws for you sometimes. In Mexico City I began to study Latin America for real and realized I wanted to write about it as a journalist. If I hadn’t become a journalist, I realized, I wouldn’t have met my husband, also a journalist. And if I hadn’t met him, I certainly wouldn’t have wound up traveling in Chile with our daughter.

In a sense, Chile had come full circle, too. Even as I was applying for my ill-fated Fulbright, the CIA was secretly planning and financing the 1973 coup that would usher in the 17-year dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet. Last year, Pinochet died at 91, outliving years of international efforts to put him on trial for human rights abuses, and Chile elected as president the daughter of one of his victims, center-leftist Michelle Bachelet, an English-speaking pediatrician and single mother of three.

In Memphis, we had gone as a family to see the Lorraine Motel where Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered. In Berlin, we went to see Checkpoint Charlie. In Santiago, we wanted to see the landmarks of dictatorship Henry and I carried images of in our mind. We walked through the grassy courtyards of the restored presidential palace, La Moneda, which had been bombed by the generals in the 1973 coup and was where Allende had shot himself rather than surrender. In two minutes, we were out the other side; no tours were available. We drove past the aging gray soccer stadium where Pinochet sent for “processing” thousands of citizens who later died or disappeared. Our guide had never heard of Villa Grimaldi, an infamous police torture center, even though Bachelet herself had once been detained there and it was now a museum. A guard finally let us in when we found it, though he said we were supposed to have reservations. We walked through it in the rain, the only visitors, reading signs identifying forms of torture that had been employed in the rubble of each small chamber. Not until we drove away did the driver confide to us and to the guide next to him, what had happened to him during la dictadura: as a boy, he had been shot in the street after curfew.

Given Bachelet’s election, I had expected from afar to sense a healing, a certain dealingwith. In Germany, even in Rwanda, the past is on display for examination and debate. Instead I found something I had too little time to identify. Suspicion? Fear? Habit? Elizabeth’s program directors had advised students to avoid political conversations with their host families, and we complied, because at the end of the day I wasn’t willing to risk those slightly sappy moments that make family vacations memorable. I was a mom. My highlight of Santiago was learning to dance la cueca with Elizabeth’s other mom, the spirited Eugenia, and eating cakes her daughter baked for us, for a late-afternoon Chilean tea.

The next morning, after the rain, we awoke to see the spectacular curve of the Andes, covered head and shoulders in snow, still pink from the dawn, like a mother’s sheltering arm.

We took a two-hour flight south and rented a car in Puerto Montt, gateway to the Lake Country. It mattered to me to drive through Chile. A Southern Californian who still considers driving a kind of derivative constitutional right, the means to pursue happiness, I had once imagined writing a book about driving through Neruda’s long, thin country and was resentful when another writer—a woman!—actually wrote one. That missed opportunity had hit me harder than seemed reasonable because it was a writing off—a reminder that growing up meant growing out of certain chances, of a night years ago at a Joan Baez concert when something about the purity of her voice made me recognize (ludicrously so, because it had never been a possibility in the first place) that I was too old to be a prodigy.

We spent the first night in a jammed lakeside tourist resort, sampling the region’s German pastries and watching end-of-summer fireworks over Llanquihue, one of South America’s largest lakes. The next morning we drove past Osorno, the perfect black-sand volcano that towers over the lake, and followed a dirt road to a family-run fishing lodge called Ruca Chalhuafe. A few hours later, we were as far from Santiago as I could imagine, drifting down the Petrohue River, watching salmon jump so close we could hear them plop back into the green water. We weren’t experienced fishermen, however, and they eluded us. The best spots were still downstream, the guide assured us after a picnic lunch. Did we want to fish for medium salmon or large? What sort of question, I wondered, was that?

Elizabeth and I cast at precisely the same moment when we shoved off again from shore. There was a sudden tangle of lines. I willed myself to look down. Two barbed hooks of a large-sized spinner dangled near the vein inside my wrist. The third hook was hidden, buried up to its hilt in the heel of my hand. The three of us sat for a few hours and waited at a remote and beautiful river bend while the guide hiked out for help.

Elizabeth said she thought I was brave. “It doesn’t hurt if I stay still,” I said. I felt lucky to be in this place. “Would you have chosen to come to Chile if not for me?” I asked, a question I had put off. “You’ve got it backwards,” she said. “I almost didn’t come to Chile because I didn’t want to be living your dream.”

We had planned to stay for one night and stayed for four. We fished the rest of that green river and jumped into a hot spring in full yellow waders in the rain. We woke up to little apples falling off a tree that seemed to grow more of them overnight so it could start out full again the next morning. I have a picture of me waving from a rental car with a left hand bandaged by a surgeon who greeted his patients with a kiss on the cheek. Not the Chile I had envisioned, nor the me I had envisioned driving through it, but hadn’t Pablo Neruda said of his poetry, when he accepted the Nobel Prize, that it was regional, painful, and rainy?

Concluding our family’s threeweek saga, we took another two-hour flight south, this time to Punta Arenas, the historic port on the Strait of Magellan that lost its position in history the day the Panama Canal opened. We drove north from the airport, through vast stretches of land denuded a century ago for sheep ranches, past minefields set during the Malvinas (Falklands) War when tensions between Argentina and Chile were high. It was late when we arrived at Torres del Paine, the national park that is considered one of the world’s last unspoiled wildernesses. The moon rose, sudden and full, and an enormous wall of stark gray shapes loomed, making everything else small and quiet, and I felt as if I were inside an Ansel Adams photograph.

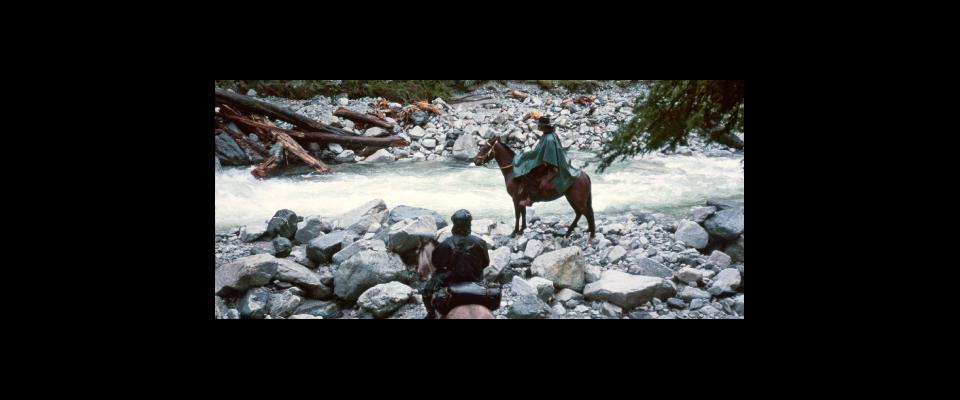

The peaked “horns” of the landscape dawned a different color each day, and we hiked around them. Elizabeth and I rode horseback up into windswept hills that reminded me of a Brontë heath, only wilder by far, and returned at the end of the day to hear the music of huasos, Chilean gauchos, on the radio. We danced in the dirt. And I recognized that I had traveled way beyond my original expectations, for I could not have imagined so long ago a grown daughter chasing joyfully after a lumbering guanaco, or my husband staring, transfixed, at the impossible turquoise of a glacier, or flamingos stepping through ice. There is a place near a waterfall in the park that is one of the windiest places on earth in summer. Caudaloso, I thought in Spanish—I had learned that word from Neruda, a word for mighty rivers—as I leaned near it, holding hands with my husband and daughter and leaning into a wind so powerful it kept us from falling.

I had left a week for myself unplanned after Elizabeth had to return to classes in Santiago and Henry had to fly home to work. I chose to explore Punta Arenas, finding a surprisingly sophisticated little city full of clues to follow to a flinty past that had made of Patagonia something neither Chilean nor Argentine, but a merging of immigrants Basque, Czech, German, Welsh, and others who understood sheep or saw fortunes that could be made from them. I visited a peat bog that had fueled explorers’ fires and followed the footsteps of a historical figure, controversial long after death, whom I thought would make a good book. I began taking notes.

I went in search of the famous “end of the earth” but it proved harder to find than I imagined. There were places that, for reasons of tourism, advertised themselves as such, but where did the earth end when it dissipated into ever-smaller droplets of islands divided by waterfalls and fjords?

I boarded a large ferry that went up the windblown Strait of Magellan to Isla Magdalena, home to thousands of pairs of nesting penguins. On the advice of the ferry mechanic, I climbed to the top of an old lighthouse while other passengers took pictures of the birds. There, alone in an outpost from another century, I looked out at the passageway that Fernando de Magallanes had spent more than a month navigating nearly 500 years before and found myself in a kind of pointillist painting come alive. Everything was moving, speaking. Below me, the soft braying of the penguins, their nests connected by a web of tiny footways across the island; around me in the air everywhere the crying of seagulls and sharp-tongued kestrels; and beyond all of us out over the expanse of navy-blue sea, flocks of white caps that Patagonians refer to as ovejitas, or little sheep. This is where the earth ends, I declared to myself, for I could.

The day before I had to leave Chile, I made my one true pilgrimage, to Isla Negra, the house Pablo Neruda had built on a beach south of Valparaiso. This man knew his real estate, I thought as I drove up. I had read about it years ago, with its magical collection of figureheads and miniature guitars and huge beetles. He didn’t just write odes to common things, he built rooms around them like three-dimensional metaphors that went way beyond any crossing of brain wires that lends taste to sound. What I loved was seeing the fun he had made of this all. An iconoclast and a onetime diplomat, he called himself captain of this place, stuck an open wooden fishing boat in the sand, and served drinks on board. He said it was better to be dizzied by alcohol than seasick. Passionate, iconoclastic, he acquired a full-size statue of a horse from his hometown and threw it a housewarming party. Two guests brought horsetails, so today it has three.

I had lost patience for poetry over the years (I pledged to find it when I got home), but I felt compelled to ask a museum guide what Neruda had meant by that seemingly sexist line, Me gustas cuando callas porque estas como ausente. “I love you when you are silent because it is as if you are absent.” But my mind wandered during her long, involved answer. I preferred the spontaneous explanation of a woman who sells that sentence to tourists, embroidered, painted, or glittered onto souvenirs: it’s for husbands, she laughed, they buy it for their mothers-in-law.

Before leaving, I sat down on the stone bench that had been built for admirers to contemplate his gravesite and looked beyond it to the rugged coastline. I stared beyond it at the beautiful sweep of beach, black rocks, and pounding blue and white surf. Eight pelicans flew south in a missing-man formation. A freighter plowed the horizon north toward Valparaiso and disappeared in a fogbank that reminded me of home. Had I invented a Chile of my own? Conjured it up, a place far from home and family where I could invent myself? And for the first time in years I thought of the other selves I might have become back then: the botanist, the carver of chairs, the mother of boys, the inventor of board games, the speaker of Swahili, the architect of public spaces, the philanthropist, the writer of stream-of-conscious novels, the lawyer, the builder of brands, the maker of maps, the surfer girl. Tiro mis tristes redes a tus ojos oceanicos, I said to most of them (though not all) in a Castilian accent. “I cast my sad nets at your eyes that are as deep as the ocean.” And I let them go.

From the July August 2007 Summer Travel Issue issue of California.