Fooling a deadly virus could stop hepatitis C

The virus that causes an often deadly form of hepatitis has long vexed scientists searching for a cure. An estimated 2.7 million Americans have chronic hepatitis C, and most of them will suffer irreparable liver damage.

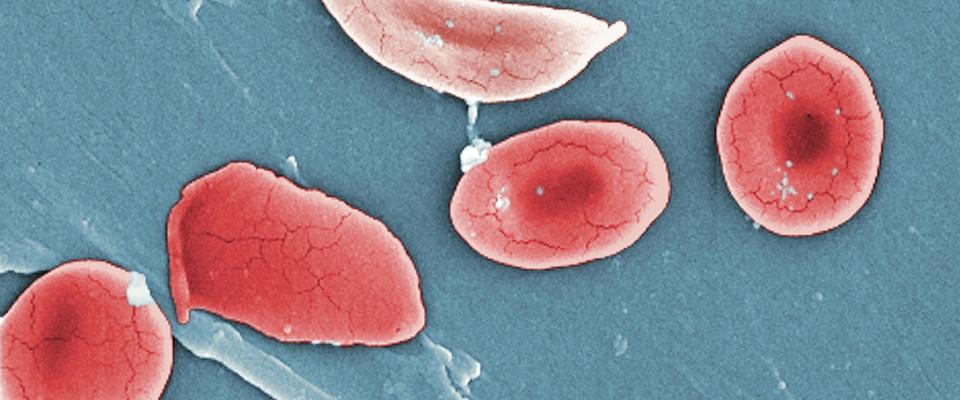

Spread by intravenous drug use and other contact with contaminated blood and body fluids, the virus is insidious. Like other blood-borne viruses, including HIV, hepatitis C takes over a cell’s protein-manufacturing processes and uses that machinery (the “ribosome”) to make copies of itself, even when the cell tries to shut it down.

This cellular trickery is the focus of research by a team of Berkeley scientists trying to beat the virus at its own game. Team member Jennifer Doudna, a professor of chemistry and molecular and cell biology, has worked for several years to identify how the virus does its damage. Scientists knew about the hepatitis C virus’s ability to hijack the cell’s basic infrastructure. But Doudna and her colleagues believe they now know more precisely how the virus does it, and how it defeats cellular defenses. Working with biophysicist Eva Nogales, associate professor of molecular and cell biology, the two used a technique called cryo-electron microscopy to make images of the viral genetic material—RNA—bound to the cell’s protein-synthesizing machinery. (The latest chapter of their research was published in the journal Science in December 2004.)

A ribosome is composed of two parts that wrap around a piece of messenger RNA, the body’s blueprint for making proteins, only after detecting a “tag” called a binding cap that ensures the RNA is authentic. But when hepatitis C invades the cell, it displaces the binding cap and mimics the messenger RNA, fooling the ribosome. Having disabled the on-off switch, the virus continues to manufacture copies of itself even when the cell tries to shut down the ribosome to fight the infection.

Team members expect their improved understanding will eventually lead to a treatment. “One of the biggest barriers to finding good drugs is finding the Achilles heel of the virus,” says Doudna. “We think we’ve found one.”

From the March April 2006 Can We Know Everything issue of California.