The experimental music of Conlon Nancarrow moves from pianola rolls to the stage.

Question: When you compose for the player piano, do you try to avoid writing something that a live pianist could realize?

Nancarrow: Oh, no, not at all. I just write a piece of music. It just happens that a lot of them are unplayable.

—From a 1980 interview

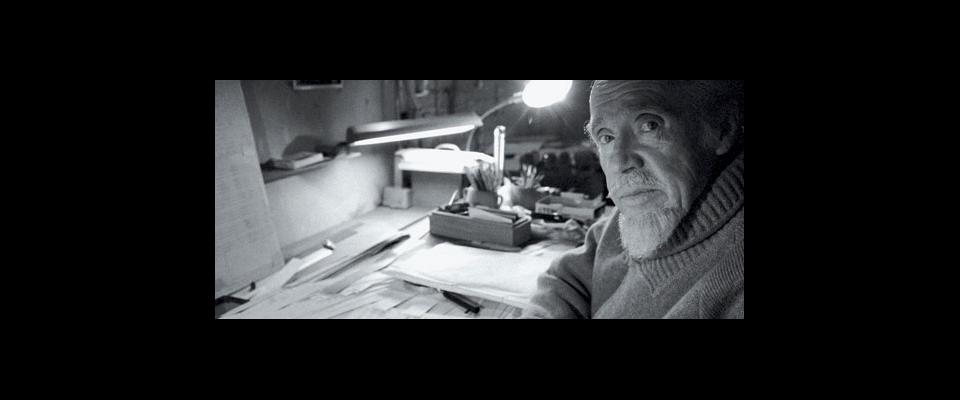

The visitors who made it to Conlon Nancarrow’s home in Mexico City noticed that the composer had extremely muscular forearms, the result of decades of using a stiff mechanical hole punch to perforate old-fashioned pianola rolls. Nancarrow wrote compositions so rhythmically complex that seemingly no musician could execute them. For almost 40 years, his orchestra was an Ampico Player Piano, mechanically reproducing scores he “wrote” by punching thousands of holes in pianola paper rolls. Most of his works last less than five minutes, perhaps due to the physical labor involved in their creation. Nancarrow once estimated it took ten hours to punch out ten seconds’ worth of music.

Nancarrow’s works are counted among the most intriguing efforts in modern American music, but it’s their sheer difficulty that makes them irresistible to Alarm Will Sound (AWS), an innovative 20-member band that plays music from Aphex Twin to Frank Zappa, on everything from conventional stringed instruments to the electric marimba. AWS comes to Hertz Hall on Sunday, March 11 to perform some of the most complex—and most accessible—experimental music of the 20th century.

“It’s like Mount Everest,” says AWS managing director Gavin Chuck of Nancarrow’s work. “It’s there, so you want to climb it. Nancarrow believed musicians couldn’t perform his pieces correctly, which may have been true at the time he wrote them. But we want to take on the challenge. To capture the thrill of performing live something that was created for machines.”

And then there’s the fascination with Nancarrow himself, whose identity coils around twin helices of musical and political radicalism. Given his ornery iconoclasm combined with an obsessive interest in form, his seemingly congenital disgust with the U.S. government, even his vertical hair and prophetic mien, Nancarrow feels like music’s answer to Ezra Pound, another gentile modernist who turned an old art form upside down and shook out something new.

Born in Texarkana in 1912, Nancarrow grew up in a conservative household that happened to have a player piano. He hated school and, starting at age ten, secretly used his allowance to buy educational pamphlets published by the International Workers of the World. He briefly took up piano but hated his teacher and switched to trumpet instead. Later, while attending Cincinnati College-Conservatory, he heard Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring for the first time and realized he wanted to be a composer.

Nancarrow moved to Boston to study music seriously and joined the Communist Party, even organizing a concert to commemorate the death of Lenin. And he truly walked the Red talk: When the Spanish Civil War broke out, he made passage across the Atlantic by playing in a cruise ship’s band, and immediately joined the anti-fascist Abraham Lincoln Brigade. Interviewed in the 1980s by William Duckworth, the composer’s response to questions about his wartime experience is classic Nancarrow: matter-of-fact, unsentimental, no quarter for fools.

Duckworth: Did you see a lot of action in the Spanish Civil War?

Nancarrow: Two years of it.

Duckworth: I mean, were you in the thick of things, so to speak?

Nancarrow: Of course.

Duckworth: Being fired at and all that?

Nancarrow: Well, naturally! That’s what wars are about.

After the defeat of the Spanish Republicans in 1939, Nancarrow barely made it back to the States, smuggled out in the bowels of a freighter carrying olive oil. Then two documents changed his life forever. In New York, Nancarrow bought Henry Cowell’s New Musical Resources, which proposed that “highly engrossing rhythmical complexes could be easily cut on a player-piano roll.” And in 1940, the U.S. government refused to renew his passport, driving a fed-up, poor Nancarrow into exile in Mexico, where he would live and write, virtually unknown, for nearly 40 years. He came back to the States just long enough to purchase an Ampico Reproducing Piano and a custom-made punching machine to create his own piano-roll scores.

Despite Nancarrow’s extreme experiments in rhythm, his music is surprisingly accessible, says AWS staging director Nigel Maister, artistic director of the University of Rochester’s International Theatre Program. “Nancarrow’s work doesn’t have an aggressive, intellectualized feeling. It’s jazz inflected. And player pianos carry a certain part of the American psyche. They belong to the world of parlor tricks, silent movies, Tin Pan Alley. These works are hugely evocative.”

Nancarrow composed more than 50 rhythmic studies for player piano, an outsider artist living a near-hermetic existence, supported in part by his third wife, archeologist Yoko Seguira. But his work slipped under the border and found its way to John Cage and Merce Cunningham, whose 1964 world tour featured dances choreographed to several of Nancarrow’s player-piano studies. Among a small, elite group—which came to include György Ligeti, one of Nancarrow’s most vehement champions—the composer found an audience.

That audience grew after Nancarrow won a MacArthur “genius” grant in 1982 and received some commissions, seeing his work performed by major orchestras before his death in 1997—about the time an ambitious group of students from Rochester’s Eastman School of Music started to rethink how new music could be presented to audiences.

The ensemble, which eventually morphed into AWS, “knew from the start that we weren’t going to just sit behind music stands and play,” says Chuck. “To wear the usual all-black and be invisible. Of course we want the primary experience to be the music. But the performers need to be front and center to help that happen.” Or in transit. An early concert of a Benedict Nathan piece had AWS boarding a Manhattan Gray Line tour bus—still playing—as the audience looked on in astonishment.

AWS insists that gratuitous theatrics are the last thing on their mind. They’re looking for the most effective means to unpack a piece of music for an audience—wherever that takes them. And unlike many chamber orchestras, AWS is rife with composers, whose skill set allows them to investigate the structure and possibilities of new music in rigorously inventive ways.

“The particular study I arranged, Player Piano Study No. 2, is very typical of Nancarrow’s techniques,” explains Chuck, who teaches music theory and orchestration at the University of Michigan. “It’s basically playing the same blues tune at four different speeds, simultaneously. Nancarrow layers them one on top of the other. So on one level, what he’s doing is quite straightforward. These are simple dance rhythms. But out of that simplicity comes a complex rhythmic surface. There’s a feeling of order and chaos at once. To dance to this music, you’d need five feet.”

AWS asks not only what a piece of music sounds like but also what it looks like. “New music can feel hard to listen to,” says Maister. “But watching it live makes it so much more approachable, especially once you get to see what’s going on between musicians.” Maister views his role in an AWS concert as visually “clarifying the mechanics of a piece.” Through subtle shifts in staging—say, changing which musicians are grouped together on stage at any given moment—Maister offers the audience an image of how Nancarrow layers competing rhythms inside one composition.

The director also wants to remove the distancing aura of perfection that surrounds so much classical performance. Part of the audience’s experience, he believes, is “seeing the artists themselves come to grips with a piece. I try to push that up a notch.”

AWS artistic director Alan Pierson admits that Nancarrow is a bit of a high-wire act. “As a conductor, I conduct at one of the speeds in a composition, and everyone else has to think of what they’re doing in relation to that,” he explains. “Often, the beat that most of the players are playing is completely different from what I’m conducting. It’s disconcerting, like making a cell phone call and hearing an echo of your own voice. It really pulls at your ears and your head.”

Does the music’s sound directly reflect Nancarrow’s radical personality? Maister reframes the question. “What you hear is the ambition of the music. The complexity. There’s something utopian about it.”

And something irreducibly obsessive. “Nancarrow contributed one incredibly powerful idea to modern American music: He came up with a tool which let him write rhythms that grooved without sacrificing rhythmic complexity,” says Pierson. “And he followed this idea to its conclusion, developing this single tool for his entire career. I think of Steve Reich quoting Wittgenstein: ‘How small a thought it takes to fill a whole life.'”