The Fritz Institute gets Bay Area nonprofits ready to head up relief efforts when disaster strikes.

From his tiny upstairs office in San Francisco’s Mission Neighborhood Health Center, where a large portrait of Our Lady of Guadalupe watches over the other Catholic saints covering the walls, Chris Sandoval tries to imagine how his clinic will handle a rush of traumatized patients after a catastrophic earthquake. Most of the nonprofit clinic’s clients are Spanish-speaking and uninsured, and Sandoval, the training and development director, knows that a quake’s no idle worry. The U.S. Geological Survey predicts that California has a greater than 99 percent chance of a magnitude 6.7 or larger quake occurring within 30 years.

Mission Neighborhood Health Center, a primary care facility, is not used to handling either large crowds or trauma victims. If an earthquake were to happen right now, Sandoval says, the clinic would likely lose power because it cannot afford a back-up generator. The staff has chosen a room to use as makeshift morgue, and Sandoval, an interfaith chaplain, will minister to the grief-stricken and the dying.

But the thornier problem remains what to do with the living who will flood into the clinic—particularly if the quake damages the building. “We currently serve 13,000 patients a year,” says Sandoval. “If they were all to rush in the front door at the same time we would be stampeded.”

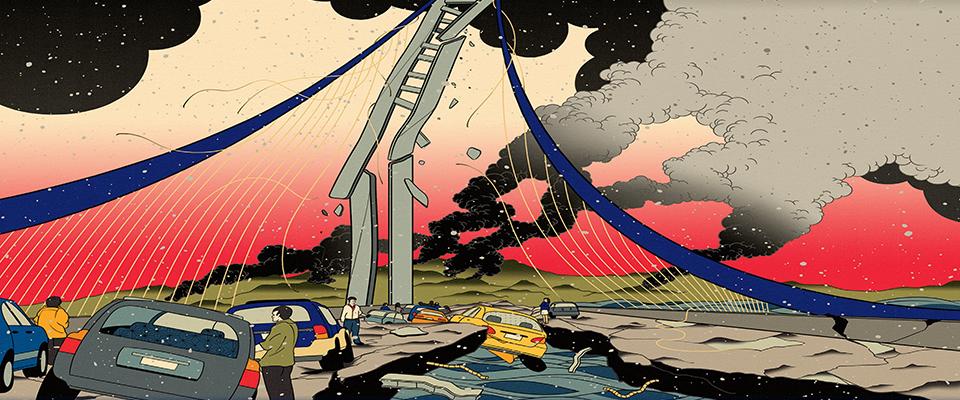

The Mission clinic’s staff is not alone in its concern. A massive quake could trigger a crippling domino effect on the community-based organizations that serve the Bay Area’s most vulnerable people: the elderly, the mentally and physically disabled, the homeless, recent immigrants. Many rely on food banks, shelters, clinics, and meal-delivery programs for their everyday survival; in a disaster they’d be hard pressed to fend for themselves.

That’s why the San Francisco-based Fritz Institute, founded in 2001 by social entrepreneur Lynn Fritz, has launched a novel program called BayPrep. Its goal is to help community-based organizations not only keep their doors open following a disaster, but become part of the rescue response. Sandoval’s clinic is one of a dozen nonprofits participating in BayPrep’s Disaster Resilient Organization pilot program, which is now going on its second year.

Can such tiny organizations really form the backbone of an emergency response? “The truth is that when a major disaster strikes on the level of a [Hurricane] Katrina or worse, community-based organizations such as clinics and shelters are the front-line responders. They provide the critical human services such as food, water, and shelter to those most in need,” says Fritz Institute CEO Robert Gordon Sproul ’69. Local nonprofits and affinity groups—organizations that reach out to people of a certain ethnicity, neighborhood, or religion—are already in place, intimately familiar with the local social terrain, and trusted by their clientele. “We help prepare them for the inevitable surge in demand for their services,” explains Sproul.

With the help of a particularly hair-raising PowerPoint presentation, Rich Eisner ’67, M.S. ’70, who spent 23 years at California’s Office of Emergency Services and now serves as the government liaison for BayPrep, shows how the Bay Area’s social safety net might collapse if organizations fail to prepare now for a disaster like 1906’s 7.8 magnitude San Francisco quake or 1868’s 6.8 magnitude Hayward temblor. “Loma Prieta was a picnic in the park compared to a recurrence of 1906,” Eisner says. The Bay Area has become much more densely populated, heavily constructed, and electricity-dependent over the intervening century. During the next big quake, he says, the power is expected to go out within the first second of shaking, which will leave everyone in the dark—and possibly without communications, since many phones now depend on electricity or rechargeable batteries. Nonprofits may also lose their buildings: A recent survey commissioned by the Fritz Institute found that most San Francisco service providers are working out of elderly buildings erected in the 1920s and ’30s, of which only a fifth have been retrofitted.

And if the bridges or BART tube fail, “We would be basically looking at the Bay Area with 9 million people in it but with an infrastructure that looks like 1930, when we had a fraction of that population,” Eisner says. Nonprofits that rely on “just in time” deliveries of food, medicine, linens, and other necessities because they lack the space or funds to store them on-site will be hobbled if supply trucks can’t travel damaged roads. Transit problems would also slow the arrival of relief from the National Guard or the Red Cross.

Berkeley’s Center for Catastrophic Risk Management, informally allied to the Fritz Institute, was formed after Katrina, and specializes in studying how disasters spiral out of control. Ian Mitroff, the center’s crisis management expert, explains that when a hurricane or a quake comes along, “either due to human action or inaction, a hazard becomes a disaster.” BayPrep’s thesis is that small nonprofits have the flexibility to bend where bigger organizations might break.

But it’s often hard for nonprofits to achieve real disaster preparedness. They are chronically under-funded, and many experience rapid staff turnover. And for staff swamped with their clients’ current needs, preparing for a future disaster can be a low priority. “Initially it was really tough to get staff buy-in—they felt they were really busy, that they were already managing the crisis of homelessness every day,” says Phil Clark, director of housing development and asset management for Episcopal Community Services, which provides housing and social services for 1,500 people.

The turning point, he says, came when the Fritz Institute presented them with a detailed timeline of the devastation likely to occur in a major quake. “The general extent of the disaster, and the federal response time, was scary,” recalls Clark. And the realization that staffers who rely on a bridge each day to go to work would likely not get home, got them quickly working on a contingency plan for how to reopen all of their sites—including two shelters, ten supportive housing programs, and an education center—as quickly as possible.

Before enrolling in BayPrep’s program, most of the organizations had disaster plans that were too simple or neglected. “We’d done fire drills,” says Ashley McCumber, executive director of Meals on Wheels, which delivers food to 1,500 homebound San Francisco seniors. “But we hadn’t really gone much beyond very simple, obvious basics. What Fritz did is say, ‘Oh wait a minute—you haven’t talked about this. You really need to look more comprehensively at what you’re doing.'” That involved asking tough questions about how organizations might handle a surge in demand, both immediately after a quake and in the coming months, when job or home loss would swell the ranks of those in need.

A repeat of the 1906 earthquake could displace more than 240,000 households in the Bay Area. Competition for shelter space and other resources will disproportionately affect low-income residents who do not have the wherewithal to leave town or pay for hotels, or who don’t have stockpiles of food or cash to draw upon.

Despite the obstacles, the BayPrep participants have already made progress. Meals on Wheels, for example, has stocked eight days’ worth of food and purchased two stoves that can be powered by a generator. The Mission Neighborhood Health Center is scraping together money for a generator. Sandoval says he’s sticking to his mantra: “No Katrina in the Mission.” When the quake finally comes, he says, “I don’t want to have a 60 Minutes reporter in my face saying ‘Why didn’t you do something?'”