Imagine being told that you have a tumor in your liver. Luckily, it hasn’t metastasized, and the doctor offers you options, including surgery to remove the tumor, followed by an uncomfortable recovery period, or a combination of radiation and drugs to shrink the tumor, which might harm the surrounding healthy tissue also, and compromise your immune system in the process.

But what if there were another option, a surgical technique that could kill the cancerous cells in the affected organ without harming the surrounding healthy tissue.

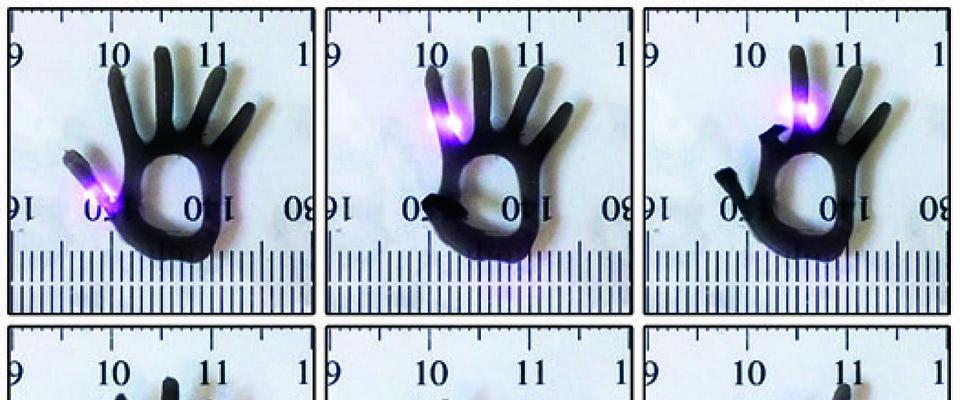

If the medical device company AngioDynamics Inc. is successful, the third option could be a reality by the middle of next year. The technique, known as irreversible electroporation, or IRE, is being touted as a minimally invasive cancer treatment in which the tumor cell membranes are made permeable by application of small electric shocks. (A similar process called cryosurgery can harm surrounding tissues.)

Electrodes are inserted into the tissue closest to the tumor and an electric current is generated, creating tiny holes in the cell membranes. The holes can’t be sealed, which leads to instant cell death. The lesions from the electrical shocks heal within two weeks. Studies suggest that because the electrical shocks are localized, major structures such as blood vessels are not affected.

If IRE lives up to the hope, credit should go to Boris Rubinsky, professor of bioengineering and mechanical engineering, and co-inventor of the technique patented by Cal. Rubinsky is also the co-founder of the company Oncobionics, which has exclusive rights to commercial development of IRE. AngioDynamics Inc. is acquiring Oncobionics.

So far, Rubinsky has shown that he can kill cancerous cells in solution using the technique; he’s also demonstrated that he can target specific, albeit healthy, cells in rats and pigs without harming nearby tissues. Next up: human clinical trials involving liver and prostate cancers, which are expected to begin later this year.

Though Rubinsky says IRE wouldn’t replace chemotherapy, because the technique would work only on contained tumors and not cancers that have metastasized and spread, it would add significantly to a surgeon’s operating arsenal. “It allows the surgeon to affect only the cell membrane. This opens the door to a whole field of applications that has not been explored yet,” he notes.

Five years from now, he says, “it will become ubiquitous in medical treatment to the extent that … everyone will take it for granted and no one will even remember who the inventor was.”