The Sigg collection tracks the rise of Chinese modernism.

The vast complex called the Dashanzi Art District was originally built to house workers and to manufacture Chinese military electrical parts and, some say, munitions. Which explains its other name, 798: Designations beginning with 7 were given to all military factories in China, helping camouflage their identity.

Today, the decommissioned military complex teems with galleries selling paintings, sculptures, and mixed-media works of modern Chinese artists, interspersed with restaurants and cafes. Its many Western-owned gallery spaces attest to 798’s growing reputation as a “must-see stop on the international modern art circuit,” according to David Lei ’72, member of the Board of Directors of San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum.

The contemporary art scene, like so much else in China, is commanding the world’s attention as the nation rockets towards modernization. The ascendancy has not gone unnoticed by the Western media, though attention often seems focused more on the stratospheric prices than on the art. Since 2002, 798 has become the locus of a thriving art scene.

Entering the iron gates, past uniformed and armed sentries, once inside the Bauhaus-style complex, The Ullens Center for Contemporary Art offered a retrospective of 1985 New Wave artists. A Book from the Sky, an installation piece by Xu Bing, dominated a nicely lit two-story, warehouse-size gallery.

Asmaller version of Xu Bing’s piece will be part of the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive exhibition Mahjong: Contemporary Chinese Art from the Sigg Collection, which will open September 10, 2008, and run through January 4, 2009.

The Sigg collection spans four decades and is the world’s most comprehensive. Uli Sigg began to track the growing contemporary art movement while he served as Swiss ambassador to China in the mid-1990s. The exhibit will feature approximately 120 works by 92 artists, including paintings, drawings, sculptures, photographs, video works, and two pieces by Xu Bing.

“To understand contemporary Chinese art, you must study the Cultural Revolution, the impact of Mao’s ideas about culture,” said Xu Bing, a MacArthur “genius award” recipient who recently spoke at the Institute of East Asian Studies and will return to Berkeley in Spring ’09 as an artist-in-residence.

His own work during that time informs his art. “My calligraphy—I wanted to serve the Cultural Revolution so I spent a lot of time in propaganda writing big word posters to contribute.”

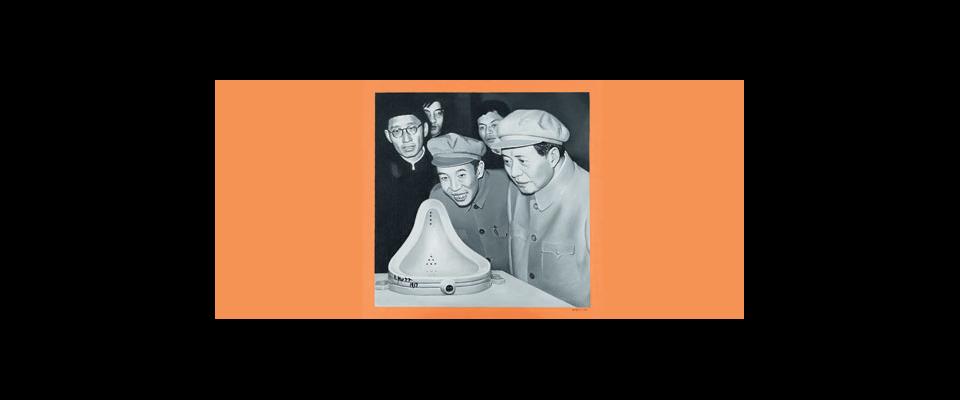

The roots of contemporary Chinese art run back to the May Fourth Movement of 1919, the mass protest against foreign imperialism that is a touchstone for Chinese artists. After its 1949 victory, the Communist Party imposed Soviet Socialist Realism as the dominant style of art, aimed at furthering the goals of the state. Mao made clear the role of the arts in a communist society when he said, “Literature and art fit well into the whole revolutionary machine as a component part.” This was particularly apparent during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), when Mao’s mission to highlight the class struggle dictated a kind of proletarian Pop art, depicting larger-than-life heroic factory workers, farmers, and soldiers, and Mao himself.

Three years later, scattered underground artists known as Xing Xing, or The Stars, organized illegal exhibits in parks, classrooms, and homes, often dispersing in an hour one step ahead of the culture police. The 1985 New Wave exhibition in Beijing comprised artists who were getting inspiration from the West. Painting dominated, but many expressed themselves in video, sculpture, performance art, and mixed media. Much of their early work is visually dramatic, at times grotesque and risqué, seemingly for shock value, ostensibly reacting to the draconian horrors of the Cultural Revolution.

Following the 1989 Tiananmen massacre, artists withdrew into Cynical Realism. While not overtly political, the art offers a view of a society in transition, often through satire or disturbing, ambiguous images. In the 1990s, with the economy booming and the government allowing more creative dissent, political Pop arrived, its artists appropriating the style and iconography of Socialist Realism and subverting the movement’s original meaning. With rising consumerism, Gaudy Art emerged, influenced by American kitsch and consumerism as well as by China’s burgeoning economy.

Lei knows the difficulty of distinguishing an inspired artist from a technically proficient opportunist. Indeed, a November 1, 2007, Time magazine article noting the influence of foreign collectors on Chinese artists, quotes then-director of the Shanghai Gallery of Art, Weng Ling’s rhetorical question, “Are you doing it for the foreign market or are you doing it for yourself? Chinese history is not just about the past 50 years, all that political Pop that sells well. It’s about 5,000 years of culture.”

In the companion book, Mahjong, Sigg admits the same difficulty. “To make a discovery, you have to look at ten trivialities. I’ve climbed thousands of steps in countless courtyards and made calls to no purpose. I met over a thousand artists.”

The BAM/PFA exhibition will present 120 or so of the finest works in the Sigg collection’s distillation of the best of contemporary Chinese art.