Beijing locals may appear restrained, but enthusiasm for the Summer Games is breaking out all over.

On a sunny “Blue Sky day” (an official meteorological phrase in smog-plagued Beijing), the very kind of clear morning all Chinese hope for on the opening day of the Beijing 2008 Summer Olympics, I take a taxi to the Olympic Green to watch a gymnastics trial competition.

The Green is home to several major venues: The iconic metallic National Stadium (the “Bird’s Nest”), site of the Opening and Closing Ceremonies, is here, as well as the eerily iridescent National Aquatics Center (the “Water Cube”). My destination at the Green is the so far nickname-free National Indoor Stadium.

Officially, the facility will not open until August 8, 2008, precisely at 8:08—no coincidence given that 8 in the Chinese culture is a magic lucky number, just as 7 is in the West. And to have five 8s opening the Games at a site that is on the same extended meridian line as the Forbidden City and Tiananmen Square…well, how cross-axially, numerologically, and feng shui perfect can an Olympics Opening be?

The media saturation reporting every Olympic factoid is relentless. During my first sojourn to Shanghai in December 2006, the CCTV stations were already broadcasting documentaries, athlete profiles, slogans, construction updates, and other related Olympics “news,” all branded by a ubiquitous pictograph logo of a bright-red dancer in a flowing calligraphic style. That same month, I watched Chinese TV broadcasters nightly and openly marveling that the national teams were kicking gold medal butt at the Doha Asian Games, dominating the mighty Japanese in practically every competition, including swimming. For many Chinese, the Doha Asian Games were a reassuring dress rehearsal for achieving dominance in Olympic gold medals.

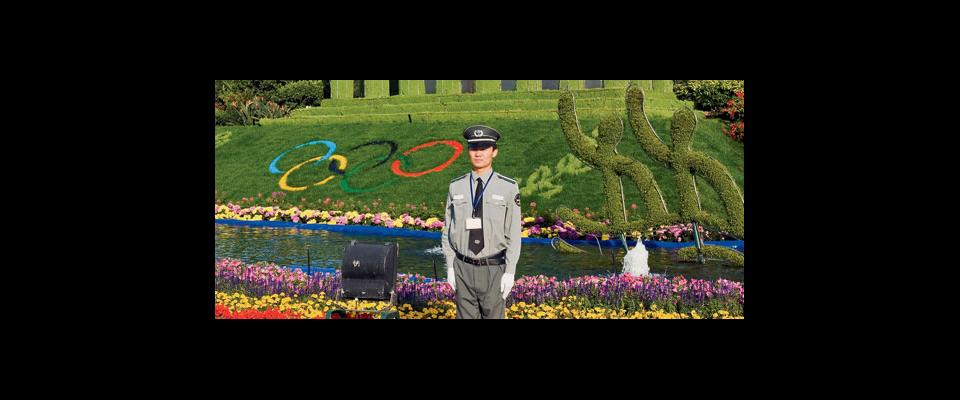

Today, BJ (as locals call it) is decked out with Olympic paraphernalia. Obelisk-like digital clocks that count down to the Opening Ceremonies tower over popular spots, especially on major thoroughfares and at tourist attractions, including Tiananmen Square. The red dancer pictograph and the five Olympic rings are integrated into electronic street ads, storefront signs, flyers, shopping bags, and product packaging for everything from cookies to electronics.

If one person is directly fueling the Chinese people’s interest in all Olympic sports, it’s Yao Ming. On billboards in malls, buildings, subway lines, and buses, the Houston Rockets star center, already a large man by any standard, looms even larger over the crowds. He’s rolling out Visa card’s newest campaign: “Only card accepted at the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games.” Yao is China’s most prominent world citizen, an overt symbol of just how strong, big, and rich China has become in less than three decades. The most-watched live TV show, broadcast during my first Saturday morning in Beijing, was an NBA game featuring Yao Ming against Yi Jianlian, star power forward for the Milwaukee Bucks—not the Rockets vs. the Bucks, you understand, but Yao Ming vs. Yi Jianlian.

The approaching Olympics have also catalyzed hot discussions of pollution solutions. Locals endlessly debate the best policies to provide those elusive Blue Sky days for foreign guests. One favored solution is to ban cars on alternating days during the Games, based on license plates ending in odd and even numbers, affecting a total of 1.3 million cars. Beijing has already deployed a fleet of new clean-fuel buses and plans to open several new subway lines before August.

Not only do locals want their weather to be on its best behavior, but they are themselves exhorted by countless ads to adopt new manners that leave a good impression on foreign visitors: not cutting in line, not pressing into pedestrians next to them, and using tissues instead of openly spitting on public streets. Olympic prep classes are mandatory for taxi drivers, who will learn a few simple English greetings and the importance of smiling at all times.

As my taxi comes within sight of the complex, the top rim of the Bird’s Nest unexpectedly glints in the sun, like a hypnotist’s mesmerizing silver pocket watch. The Bird’s Nest, which will seat 91,000 for the Olympics, is a quarter-million square meters in area, built with 36 kilometers of unwrapped steel weighing a total of 42,000 tons. The stadium’s exterior metal bands chaotically and daringly twist in and out with abandon, like scattered strands of a clutch of linguini suspended in air. Construction vehicles parked along the top rim resemble tiny Tonka trucks, underscoring the immense scale of the stadium. (Some BJs grumble about the enormous sums spent for momentary national vanity and about construction funds that may have been “misdirected” to well-connected contractors.)

The Water Cube is a steel-frame structure clad with 100,000 or so square meters of a very thin, pillowy material that is more light- and heat-efficient than glass. In the bright morning light and against blue skies, the Water Cube looks like the world’s most expensive bubble-wrapped Costco warehouse, akin to the installation work of Christo and Jeanne-Claude.

In fact, both venues are more like modern art installations than buildings. Neither is finished, and the drumming noise from incessant pounding and drilling continues unabated, evoking the thunderous Chinese ritual that signifies the ending of one dynasty and the beginning of a new one. (Those who watched CNN on the eve of July l, 1997, when British Hong Kong reverted back to China at midnight, saw legions of traditionally costumed men covering Tiananmen Square, huge drums slung sideways against their hips, beating in unison.)

To avoid a long line, I enter through a side entrance of the National Indoor Stadium. Inside, a young lady dressed in red silk greets guests in front of a giant red welcome banner and rows of potted red carnations. The vast gymnastics floor includes a large mat for floor exercises, uneven bars, a vault table, and a balance beam. An announcer booms out in American English, “The competition is going to start soon.” Many of my student friends at Bei Wai, where I was lecturing on my book, The Eighth Promise, have volunteered to work at the Summer Games. English is the foreign language of choice and many bilingual students have been recruited; every university in Beijing now plans to close in August.

Polite and efficient, young men and women help us to our seats. A French contingent sitting a few rows behind us move to take over the empty first row reserved for broadcast camera operators who are flitting from section to section. A few minutes later, a single young Chinese usher smoothly escorts them back to their original seats.

Olympic fever may at times appear restrained, but it breaks out at the Indoor Stadium when groups of grammar-school children in uniforms of red, green, or blue squeal and shout whenever a famous Chinese gymnast is announced or finishes with a perfect or near-perfect stick-it landing. The women’s gymnastics team is rebuilding and not expected to score well at the Olympics. Today, though, home-crowd favorite Jiang Yuyuan, a young pixie of a Chinese gymnast, winds up with the highest all-around score. It’s pandemonium whenever she takes the floor.

Acquiescing to this enthusiasm, I stay until the last dismount from the uneven bars, the final leap over the vault table, and the last stick-it landing in the free-style floor exercises. Along with many others in the audience, and even the student ushers, I linger after the competition’s end, not wanting to leave.

Exiting through the lobby display area, I’m introduced to the “Fuwa family”—five Olympic mascots, one of each color of the five Olympic rings and each symbolizing one of the five Chinese elements. The child-appealing Fuwa look like a cutesy cross between a Teletubby and the Japanese good luck cat with the raised paw. Two of the Fuwa represent the endangered panda bear and Tibetan antelope. Their headgear incorporates patterns and design elements from ethnic minorities. Each mascot has a two-syllable name also designed to appeal to Chinese children, the first syllables of which when strung together approximate the greeting “Beijing welcomes you.” What the Chinese managed with the number 8 is impressive enough, but achieving the multi-symbolism of the Fuwa family is like hitting a triple word score in Scrabble.

The Saturday following my midweek visit to the Olympic complex, Chen Xiu, a Bei Wai grad student friend and tutor, gets me inside The Egg, as the new National Center for the Performing Arts is called. Located in the heart of the city near Tiananmen Square, the Egg is a flying saucer–like, gleaming silver-and-glass orb standing shoulder to shoulder with the Soviet-era Great Hall of the People. From a distance, centered in a wide reflecting pool, the transparent, iconic edifice resembles a fried egg, sunny side up.

We enter by descending under the reflecting pool, and suddenly our eyes are drawn upward to the rippling pattern of the pool’s water visible through the glass ceiling. We walk down a long hallway—with displays of Chinese theater artifacts on one side, and photos of major world theaters and scale models of traditional Chinese theaters on the other—and enter the main lobby. There, a matrix of escalators rocket sharply up through The Egg’s open, spacious, naturally lit atrium to several grand reception areas. Terraced lobbies afford a vertigo-inducing view of the atrium, Tiananmen Square, and the sky beyond.

The walls of the main stage are covered in silk and acoustically designed for Chinese opera and theater. Two side stages are designed for Western opera and symphonic music. Chen and I head to the top balcony of the quasi–Art Deco symphonic hall and stop to rest a few minutes in the back row. From that distance, we can easily hear the conversation of several managers standing by the stage.

If the quality of the finished Olympic buildings approaches that of The Egg’s interior, then I want to sit in the completed Bird’s Nest at the Opening Ceremonies on August 8, 2008, at 8:08 p.m. I want to watch the parade of athletes, the lighting of the Olympic flame, and the fireworks overhead. I want to be outside shouting and dancing to the Water Cube’s laser light shows and watch giant images of athletes projected onto the building’s walls. And whatever performances are scheduled in The Egg, I want to see one on each stage. I want to do all of it.