An architecture professor finds the right perspective with kites.

Charles Benton began by choosing the right kite for the strong April winds blowing at San Francisco’s Crissy Field. He had three “soft” kites stuffed into his backpack—soft because they don’t rely on stiff frames to hold their shape. He pulled out the largest one and attached it to a line. The wad of bright nylon fabric filled with wind and rose into the air, straining powerfully against its tether—powerfully enough to loft his digital camera skyward.

Benton is a professor of architecture who specializes in Building Science—that is, how buildings work. But a good chunk of his free time is spent working on a long-term study of South San Francisco Bay, notable for its patchwork of multicolored salt ponds. He goes there to “interrogate the landscape,” as he puts it, taking photographs with his kite-borne camera for a project called Hidden Ecologies. Among other things, the project has documented the restoration of a salt pond and aided in the study of endangered snowy plovers.

His efforts over the last 15 years have resulted in invitations to speak at other departments and colleges, a partnership with the Exploratorium science museum in San Francisco, and collaborations with local environmental researchers. He has also popped up in The New York Times, on CNN, and on PBS. The widespread appeal of the project seems to have less to do with environmental science, however, than it does the sheer joy of tinkering.

At Crissy Field, Benton produced a digital single-lens reflex (SLR) camera housed in what he calls a “robotic cradle,” which will hang from a suspension system clipped to the kite line. A series of tiny pulleys are employed to keep the camera stable. Controlled by a handheld remote, the motors in the housing can rotate the camera 360 degrees, tilt it on its axis, and switch the shooting mode from landscape to portrait. Most of the apparatus, aside from the camera itself, was designed and constructed by Benton. “I love inventing stuff. I’m a tinkerer at heart; it goes back to my grandfather. So I collect old stuff—old cast-off machines, typewriters, printers, floppy drives, and such—and harvest items from those.”

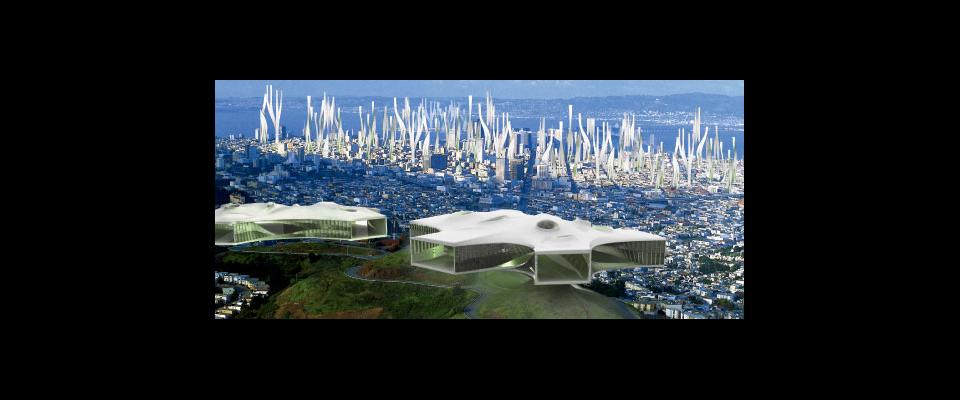

After a quick check to make sure the camera was working, he let the kite soar. When the camera was 50 feet in the air, and the kite another 50 feet above that, he began to shoot photos of the landscape below. Although a bird’s-eye view is possible from a plane or satellite, Benton has calculated that his kite photography has unique advantages. Kite-borne cameras can provide more detail than satellite images and are more economical than hiring an airplane. They can hover in one place without the rotor wash and noise of a helicopter, and they occupy a scale that is poorly covered by other methods of aerial photography. He generally shoots in a range between 10 and 250 feet above ground. In a word, says Benton, kites offer greater “intimacy.”

In the case of the Hidden Ecologies project, that intimacy reaches a microscopic level. Benton works with microbiologist Wayne Lanier to record the changes in the Bay’s environment—Benton snapping photos with his kite while Lanier, portable camera microscope in hand, zooms in on the tiny creatures swimming in the seawater. With his laptop and the gear he carries in his pack, Benton calculated he could survey the landscape over “12 decades of scale,” from the global (thanks to Google Earth) to the molecular (thanks to Lanier’s microscope).

Back at the beach, Benton leaned into the wind while pulling the kite behind him. It wasn’t the kind of kite-flying most of us grew up doing—it was hard work. While fielding a steady stream of questions from onlookers, he positioned the camera over a windsurfer, over some children, over pedestrians on a bridge, holding the line in one hand, the controller in the other, snapping shots as he went. When it was time to stop, he reeled the kite in with a ratchet block taken from an old dinghy. As it hovered about six feet in the air, Benton unclipped the camera from the line and set it down. Then he walked toward the kite, one hand running along the line to hold it steady, until he could swing at the kite with one arm in a kind of modified tackle, knocking the wind out of it—and the kite collapsed in his arms.