A Beckett favorite is as fresh as the next hour.

Barry Mcgovern remembers when the common question: “Well, shall we go?” became immortal for him. It was on a Dublin night in 1961. He was an impressionable boy of 12, already a faithful BBC viewer and a vaguely aspiring actor. On television this night the little four-word question he had already heard commonly spoken hundreds of times belonged to the voice of a downtrodden but gloriously animated stage character by the name of Vladimir, played by eminent Irish actor Jack MacGowran. And that night, the voice changed the boy’s life.

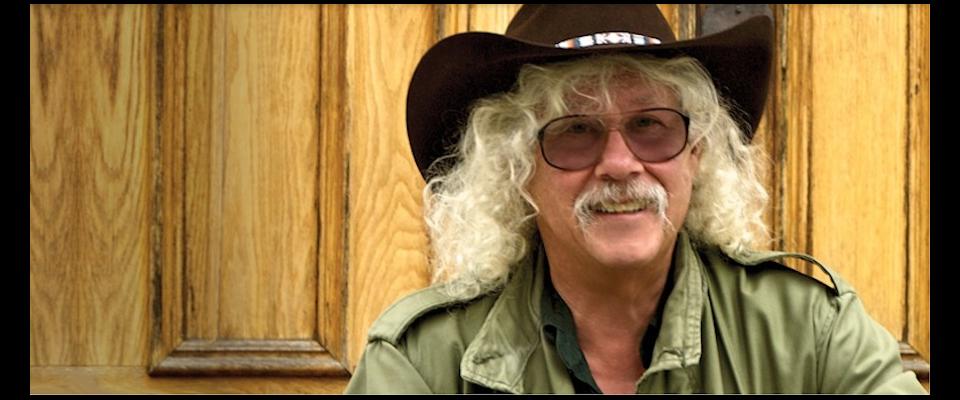

“I can’t remember as much about the words as I do the effect they had on me. The voice just rang a bell,” recalls McGovern, who would himself become one of his country’s most celebrated actors. “I felt it. More importantly, I felt I could handle it.”

Those four little words, of course, signal the climax of the two-hour play that owns world renown for showcasing the exquisite tedium of everyday life as it batters and erodes expectations and hope. It is a play so spare, yet it celebrates futility and disappointment so excruciatingly, that the late Irish critic Vivian Mercier, an admirer, was moved to describe it as a two-act performance in which “nothing happens twice.”

McGovern laughs at the cheeky characterization of Waiting for Godot, and still finds it amusing that the Samuel Beckett play he’s been appearing in for more than half his life remains the most dissected theater production of the last half-century. “I don’t analyze. I just perform. I leave the analyses to the academics and critics,” he says as self-assuredly as Beckett himself, who resolutely refused to add his own interpretations to his own play. “It’s enough for me to transform myself into the personality the writer intended. If I took on the burden of performing up to someone else’s expectations other than the writer’s…I just do the best I can.”

When he steps onto the stage at Berkeley’s Roda Theater on Nov. 1, Barry McGovern will wear the same bowler crowning the same tramp outfit that has served him through 253 prior performances playing Vladimir, one of a pair of forlorn yet comically decorous tramps from a lineage that includes Chaplin, Laurel, and Hardy. The equally illustrious Irish actor Johnny Murphy plays Vladimir’s counterpart Estragon. The two have teamed as Vladimir and Estragon since 1991. In 2000, they drew standing ovations stoically passing time with each other while “waiting” for an uncertain deliverance in front of a Berkeley audience.

This November all but closes down the Beckett centenary, and Berkeley is one of the celebrated Dublin Gate Theatre’s final venues for Godot. It is directed by Walter D. Asmus, as it was here in 2000, and critics who have reviewed the recent performances have described this Godot as “definitive.”

Which begs a question: How does “definitive” relate today to a play written, some say, as an oxymoron of Irish pessimism following World War II by a disenchanted Irish expatriate who—like his forerunner and mentor James Joyce—adopted France and embraced existentialism? In other words, why does a more than 50-year-old Godot (McGovern and all other Irish actors pronounce it “GA-doh,” emphasizing the first syllable) still draw and hold audiences, especially when they know the characters aren’t going to do anything but grow two days older and go nowhere?

Remember, too, that the first American Godot, playing in 1956 in front of a Miami audience expecting slapstick, immediately bombed. A year later it played in California’s maximum-security prison at San Quentin, and the 1,400 inmates who viewed it reportedly loved it—especially empathizing with “the wait.” The prison newspaper awarded it a glowing review and a prison drama society was formed around the play. From the dead end of San Quentin, it can be said that Godot got its actual American launch.

McGovern, in the midst of performing his one-man show I’ll Go On (from the Beckett novels Molloy, Malone Dies, and The Unnamable) at the Dublin Gate when we spoke by telephone, paused before answering why Godot still resonates. “Truthfully, I wouldn’t want to do it all the time,” he confided. “But when I leave it and come back, it feels like a long-lost child. Remember, too, lots of things happen in the play besides waiting. They talk, they argue, they plead, they cajole. Listen to the dialogue. They play games. They act out for each other. They scorn and they empathize. There is as much going on here as there is in any Chekov play, as far as I can tell.”

We can take that to mean: “Recognize and resign yourselves to the little things. We own little else, rarely our fates, and most certainly not the passing of time.” From Samuel Beckett we take our bitter medicine.

Barry McGovern played his first Beckett role as Clov in Endgame, while studying at University College Dublin. His first appearance in Godot came two years later, in 1972, when he played Lucky, who appears twice, walking on all fours and restrained by a leash. Lucky, when allowed by his imperious master Pozzo, delivers the play’s wildest and most profound soliloquy, as he wonders to himself and to the audience how he ever allowed himself to become and stay another man’s slave. But the rueful character of Vladimir, whose dignity visibly declines as he waits in vain for the promised arrival of an unknown Godot, spontaneously delights in the tiniest of trivialities, giving McGovern his best expression.

“He fits my personality, the shape of my thoughts,” he says. “Likewise, Johnny Murphy is a born Estragon. The role fits like a glove.”

McGovern also vividly remembers meeting Beckett for the first time. “I had done a one-man show at the Gate in 1985 for the Dublin Theater Festival. Beckett had been invited. Naturally he declined. [The reclusive Beckett disdained the notoriety that went with his being awarded the Nobel Prize in 1969, and refused to attend the acceptance ceremony.] But we were about to open a performance in Paris and he accepted my invitation to meet.”

Almost 80 years old at the time, still tall but gaunt, Beckett was beginning to suffer from emphysema. McGovern nonetheless was struck by his bearing; his skeptical, hawkish, iconic face; and most of all the ice-blue eyes (“like Paul Newman’s”) of the master playwright assessing the master actor from across a table in a small café near Beckett’s home in Montparnasse. “He was still very sharp. He was congenial. He was complimentary. He was grateful for the bottle of Irish whiskey I’d brought him. He said he had heard recordings of my performances,” McGovern recalls, and then adds fondly and waits for the irony to sink in, “He also asked if it was raining in Ireland as usual.” Definitive Beckett. Pure Godot.

“We had a beer and smoked small cigars…I wished I’d asked him more,” says McGovern, meaning during the remaining three years of Beckett’s life, when the two met at least half a dozen more times. “I’d been such an admirer of his work. But the work is the work and the man is the man. I admired the man, too. But I wished I’d asked him more about the myths about the work,” says the actor, a trace of melancholy shading his Irish syntax. “But he didn’t like those myths. He was just keen to get things right.”

For Barry McGovern, getting a universal play about Everyman right sometimes “turns into a Beckett albatross around my neck. But I mean that fondly.” Then he renders a smidgeon of his own interpretation: “Waiting is a universal phenomenon. Godot has a resonance for everybody. The tension of time passing is as large and painful as anything.”

But immediately he adds: “In order to keep going, to continue to play in Godot, I cannot get pretentious or take myself too seriously. Whether I’m playing in Dublin at the Abbey or the Gate, or at the West End in London or on Broadway, when the curtain comes down, I leave Vladimir behind, shower, and go get a beer.”

So in Barry McGovern’s real world, he can ask the question “Well, shall we go?” and at last take action. You might wonder, though, if given the choice, whether Beckett would consider that a more fitting end or just another beginning.

From the November December 2006 Life After Bush issue of California.