It’s not easy selling moon shares in today’s market.

James Flowers, who plays chess on the corner of Bancroft and Telegraph, recognizes Barry McArdle immediately. “Hey, that’s the guy who used to sell land on the moon. I bought three acres!” he says.

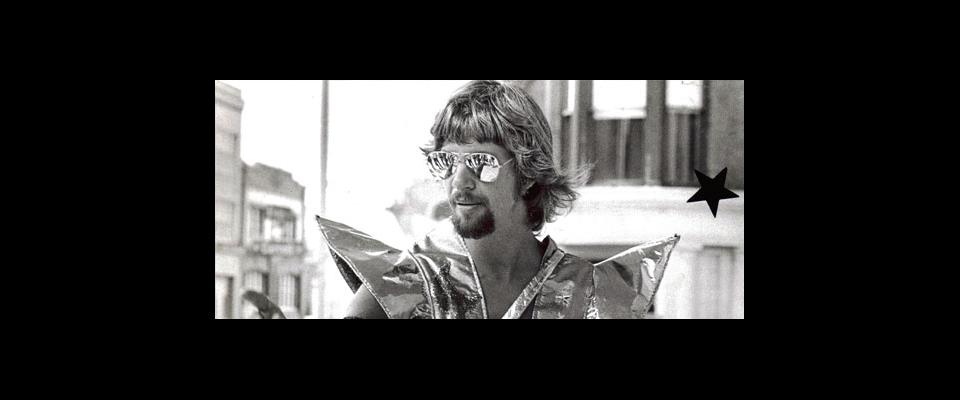

That was 30 years ago. Today, McArdle is a gray-haired man in a tasteful spaceman costume. He steps onto a nearby planter ledge. “Ladies and gentlemen!” he booms. “Only in Berkeley, one day only, the moon man is back by popular demand! Your parents may have told you about me. Land boom on the moon! Five dollars an acre, no transportation provided. Take a chance on lunacy!”

Most passersby, chatting on cell phones or plugged into iPods, keep walking. A few squint up at McArdle and then keep walking.

“Is there anyone out there willing to support individuality? Creativity? Originality, spontaneity? Anybody? America? Have we gotten that afraid? Is it that different than 30 years ago?” he asks and then answers himself. “I guess it is.”

But then, a young woman wearing a “Peace And Love” T-shirt sits on the planter next to McArdle’s open, silver briefcase. The briefcase is filled with copies of his new book, I Sold the Moon!, which chronicles how, for more than a decade after he graduated from Chico State in 1971, McArdle capitalized on the “anything goes” spirit of the times. He made his living hawking ownership certificates for moon acres on college campuses in California, across the country, and in Europe. The book includes photos of a young McArdle, in a flashier, ramshackle moon-man suit, standing on the same Bancroft planter while dozens of people happily listen to his routine. Back then he sold the acres for a dollar each and often raked in $400 or more a day.

“I am the original moon man,” McArdle says, stepping down to talk to the young woman. “I claimed the moon in ’71. I sold 170,000 acres. I have no legal right to do what I’m doing. None, zero. But here’s the interesting thing—nobody has the right to say that I can’t do it, because they themselves don’t own the moon.”

“So are you saying you went to the moon?” she asks. McArdle laughs and shakes his head.

“When I got out of college, before you were born, all the dropouts had the jobs and I decided I needed a job,” he says. “I was very into space and space travel. Neil Armstrong had just been to the moon. All I did was make a legal claim on the moon itself. Nobody has verified it, but it can’t be said to be illegal, because who has the right? Is it our government? The Russian government?”

He shows her a moon-acre certificate. “There’s no question you’re taking a chance. It’s a gamble,” he says. “But the conversational value alone—it’s a conversation piece, a collector’s item.”

She listens attentively and then politely excuses herself.

McArdle accepts an invitation from Flowers to play speed chess. He loses. McArdle steps back up on the planter. Again, no one stops.

“Grim,” he says. “Real grim.”

McArdle doesn’t need the money these days. He drives a silver Mercedes. He and his wife, a neuropsychologist, own a Bay Area home and some rentals. But he’s nostalgic for his moon-man days when, he feels, people weren’t so preoccupied. So after a long, successful career in media production, he left his job a few years ago to write I Sold the Moon! McArdle believes his story can inspire people to pursue their own wacky dreams. The book has gotten some good reviews, and his agent has sent packets to Letterman, Leno, and Oprah. He hopes someone will want to make a movie about his life.

“Back then, people expected anything,” he explains. “There were the weirdest things going on. Everybody wanted to know: What’s your trip?”