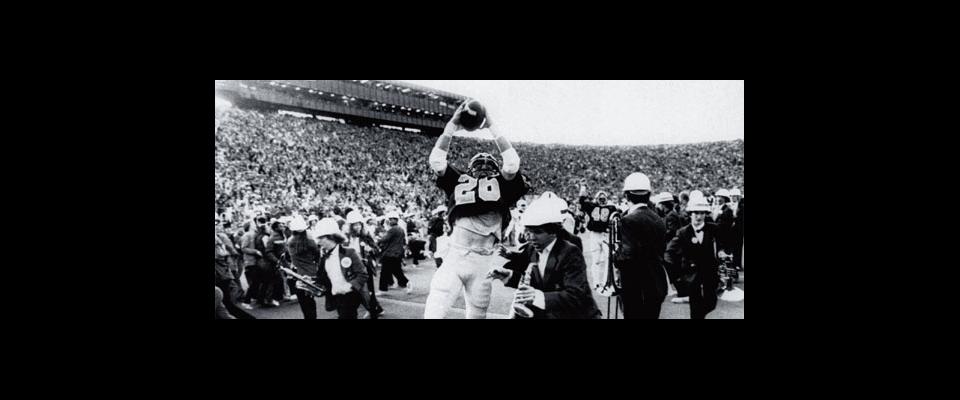

The names don’t roll off the tongue like the fabled Chicago Cubs double play combination of Tinkers to Evers to Chance, but for 80,000 football fans in Memorial Stadium, and for generations long since departed and those yet to come, the names Moen to Rodgers to Garner to Rodgers to Ford to Moen signal retribution, redemption, exultation, and hope. A squib kick with four seconds remaining, followed by a flurry of desperate pitches and laterals, backwards and sideways, took the Bears to their rendezvous with a trombone in the end zone and the impossible touchdown that sealed victory in the 85th Big Game 25 years ago this November.

The Play lives. Joe Starkey’s hysterical call is seared in the minds of those who were there, those who claim they were there, and those who wish they had been there. Countless gallons of ink have been spilled describing The Play, analyzing The Play, deconstructing The Play, and wondering whether Dwight Garner was “down” or whether the Mariet Ford–to–Kevin Moen finale was an illegal forward pass. The Play now merits its own Wikipedia entry and pops up first, before anything Shakespeare ever wrote, on Google.

Yet, the political/cosmic/karmic aspects of The Play remain largely ignored, particularly for those of us who were “down” in the ’60s, blocking entrances at the Sheraton Palace and a police car in Sproul Plaza during the Civil Rights and Free Speech Movements. In those days, Cal sports and left politics were often viewed as polar opposites. The choice was ours to make, bellowed FSM leader Bettina Aptheker from the steps of Sproul Hall: You could go to the Big Game or attend the FSM rally scheduled the same day. That choice—the Bears or the barricades—was particularly daunting for my friend Henry Weinstein, now the Legal Affairs writer for the Los Angeles Times, and me. At the time, we happened to be the student broadcasters for the Cal football games on KAL radio (then an AM station with a listenership that rarely exceeded a minyan). Henry and I were with Bettina 110 percent, but Craig Morton’s right arm called us more forcefully that Saturday afternoon—a game which the Bears went on to lose 21–3.

A quarter-century now separates us from Starkey’s breathless description of the “most amazing, sensational, dramatic, heart-rending, exciting, thrilling finish in the history of college football.” It’s 43 years since Mario Savio electrified an FSM rally with one of the great speeches of the 20th century: “There’s a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that … you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus, and you’ve got to make it stop!”

It’s time we finally consider The Play as metaphor. The Play, it turns out, provides lessons for those of us who still cling to the principles that fueled us in the ’60s and, who knows, perhaps for all of us.

Lesson 1: It’s Easier to Move to the Right than Stay Left. When Moen grabbed the squib, his initial instinct was to go left, but he was hemmed in like Hillary’s health care plan. From there, Moen and his crew did what politicians always do, they moved to the right. In fact, the whole play unfolded on the right side of the field. Depressing? Sure, but maybe Lessons 2 and 3 will help.

Lesson 2: Patience Counts and Can Lead to Unexpected Celebrations, Even Defining Moments. For Bear fans, patience is not a virtue, it is a necessity. Sure, times are flush in the Tedford era; but it won’t last—count on it. And frighteningly, at times when the left seems to be gaining momentum as it did in the ’60s, Cal sports’ fortunes seem to dim—witness eight of ten Big Game losses during a decade when Janis Joplin and Jefferson Airplane played the Fillmore and Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X visited the campus. But The Play reminds us that no matter how grim things may seem, things can turn around! If The Play had happened in the third quarter it would still have been a great play, but not The Play. No Stanford band in the end zone, no hysteria! It was worth the wait and the heartache. Write that down.

Lesson 3: Sometimes to Make Progress You Have to Go Sideways and Even Backwards. There is an irony in football that I suppose is grist for all of our mills: When you’re in the worst trouble, if you want to get ahead, you can’t go forward. Passing forward was Mariet Ford’s supposed transgression, a Stanford argument that failed to hold sway that day. This principle can get very complicated and depends, as we lawyers like to say, “on the totality of the circumstances.” Wikipedia’s analysis would have Einstein shaking his head: “Because both players were in full stride, and because the lateral traveled some distance, the ball appears to have traveled backwards relative to the two players’ forward motion, but forward relative to the stationary field.” Whether that articulation would have changed history is not the point. Progress, it turns out, is a state of mind and direction is all relative to the final outcome.

Lesson 4: Geography Matters, Particularly in Berkeley. This is a corollary of Lesson 3. Forty-five years in this town has taught me many things, but the most critical is that you can’t over-generalize based on your geographic location. The Play happened at Memorial Stadium and could not have happened at Stanford. What happens in Berkeley often can’t happen anywhere else. Berkeley doesn’t happen in Peoria or even Manhattan, for that matter. A depressing fact for us on the left? Probably. On the other hand, at least we have a taste of what it’s like to have normalized relations with Fidel and an electorate that on more than one occasion has voted to end the war in Iraq!

Lesson 5: Mythology Matters. Mythology can be dangerous. Consider the mythologies of Hitler, Stalin, and Pol Pot if you doubt that proposition. But mythology can be sustaining and must not be completely dismissed. Singer, songwriter, and UC Santa Cruz mathematician Tom Lehrer sang about the Spanish Civil War, reminding us that “we may have lost the war, but we had all the good songs.” The Play is a reminder that good songs can go a long way, and The Play ranks right up there with Beethoven’s Fifth.

When November 20 rolls around, The Play will rightly get the press it deserves. Arguments will be rekindled, Starkey will be endlessly interviewed, and sad facts like Mariet Ford’s imprisonment for murdering his pregnant wife and 3-year-old son will be recounted. But at the quarter-century mark, it’s the larger lessons that deserve our attention. So the next time you’re watching the Bears on your 50-inch flat screen, I urge you to bring along your laptop and watch The Play and Mario Savio on YouTube and consider what life is really about!