The new Berkeley Art Museum will combine old-fashioned ideas about public space with radical new ones about urban design and the future of art.

The last time I walked through the Berkeley Art Museum, I saw a ghost. She hovered in the corner of an upstairs gallery, wispy and sly, her hair disheveled, her body fading into transparency. She was called the Ghost of Oyuki and she was painted in the 18th century by Okyo Maruyama (1733–95), reputed to be the first Japanese artist to ever paint a ghost.

I saw other things that day as I wandered through the museum: A three-legged pitcher with an upturned spout that made it look as if it were sniffing the air. A series of photographs of rain-spattered windshields, winding roads, and stark trees by filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami. A blue Jambhala—the Buddhist god of wealth—holding a serpent and a mongoose. A disturbing construction of oil emulsion, lead objects, and steel traps on canvas by Anselm Kiefer that reminded me of meteors being devoured by monsters. A sweetly comic photograph of nine men standing nipple-deep in teal water.

None of it was familiar to me. I had never heard of the artists who had produced these works, and knew very little about the cultures that had produced the artists. I could not walk out of the museum and announce to my friends, “I saw the Kiarostamis,” the way I might announce that I’d seen the Matisses on display this summer at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, or the Rodins at the Legion of Honor. And yet, when I left the Berkeley museum, both my imagination and my curiosity had been ignited. Why a ghost? Why a mongoose? Why a windshield? Why steel traps?

Kevin Consey, director of the Berkeley Art Museum for the past eight years, has been spending a fair amount of time thinking about what an art museum should do or be, particularly one that must serve the needs of a leading research university and a community of educated and opinionated citizens. A few years from now, the 15,000 objects in the Berkeley Art Museum’s collection will move from their current home—a Brutalist concrete structure on Bancroft Way—to a new building in downtown Berkeley being designed by the Japanese architect Toyo Ito. There, on a one-and-a-third-acre site currently occupied by a printing press and a parking garage, the museum will be rejoined with its sister institution, the Pacific Film Archive, which moved into separate quarters in 2000 after the current museum building was determined to be seismically unsafe. (It has since been partially retrofitted.)

The move is an opportunity to create a new museum, one that has the mission not only of collecting, preserving, and displaying works of art, but also of educating, inspiring, and sometimes infuriating the people who come to see the art. And it is not just the museum that is being remade. As it leaps from one side of campus to the other, the Berkeley Art Museum lands squarely in the midst of an ambitious re-design of Berkeley’s downtown. A new downtown area plan, which is taking shape now and will be finalized by spring of 2009, envisions an urban center of grand boulevards and open-air plazas, packed with hotels, theaters, museums, restaurants, parks, and shops. The Judah L. Magnes Museum, which has the third largest collection of Judaica in the nation, is moving to the downtown, as is the Freight & Salvage, one of the region’s premier venues for folk music. In this new context, and in a showy new building, the Berkeley Art Museum will be a public institution in a way that it hasn’t been before—a place that invites a wider community to engage the question: What role should art play in public life?

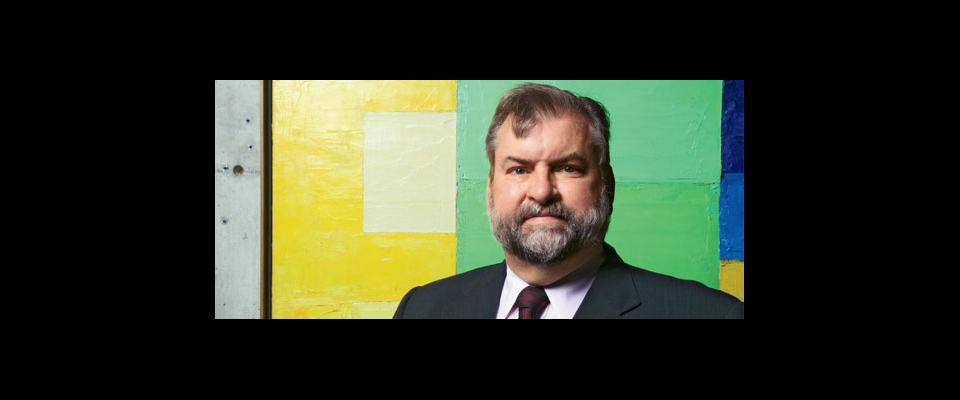

Kevin Consey came to Berkeley in 1999, having spent time as director of art museums in Texas, Chicago, and Orange County. He is a large man with a shock of graying hair, a thick beard, and the deep voice of an FM radio announcer. There is an air of weariness about him, as if he has always just come from a transcontinental flight, but that might be because he usually has. These days he spends a fair amount of time jetting back and forth between Berkeley and Tokyo so that he can meet with Toyo Ito as the architect develops his plans for the new museum. The schedule has been grueling, as have the endless rounds of meetings required by the university bureaucracy, which probably explains Consey’s surprise announcement in September that he will be retiring in January 2008 after the conceptual design for the new museum is finished.

“The completion of a benchmark like conceptual design marks a point of completion after which others can take the template and the design and raise the additional amount of money to build it,” he says. “I do not have unlimited energy and time in my life, and my assessment is that I have done enough.”

The new building will be completed sometime in 2012 and will cost between $100 million and $200 million. It will be situated on a half-block site bordered by Oxford, Addison, and Center Streets. Abutting the building to the west will be a 19-story conference center and hotel tower, which is being developed separately; to the south, Center Street will be remade into a pedestrian plaza. The building will have 12,000 square feet of programmable space, including galleries for Western art, Asian art, modern art, contemporary art, temporary exhibitions, and rotating selections from the permanent collection. There will be two specialized galleries for displaying digital media, as well as a film library, an art library, conference rooms, seminar rooms, study centers, a roof garden, and two film theaters, one with 250 seats and one with 150 seats. There will also be a café and restaurant, a bookstore, and a space for holding events.

The meeting of town and gown in Berkeley has historically been more collision than collaboration. From People’s Park to Memorial Stadium, there have been seismic rumblings whenever the two landmasses come into contact. But a 2005 agreement between the city and university—the result of a city lawsuit over the university’s long-range development plan—commits the two to a joint downtown planning process that so far has been remarkably amicable. Perched at the seam between campus and downtown, the new museum is viewed as a symbol of this newfound cooperation—a place where the two worlds might blend rather than collide.

Ito has yet to complete his conceptual design (that is expected to be unveiled in late January or early February), but the model he showed the museum’s board of trustees in September 2006 manages to be both square and sinuous. The design is a response to two opposing forces: the rectilinear grid of the downtown, and the manicured wilderness at the campus’s western edge. In melding them, Ito explodes the idea of walls, creating intersections that don’t quite intersect and curves where you would expect to find angles. Exterior walls bend inward and interior walls sweep outward, creating pockets, fissures, gaps, and crevices that blur the distinction between inside and out.

“It looks like nothing you’ve ever seen before,” says Harrison Fraker, dean of the College of Environmental Design. “He’s come up with a whole new spatial experience through this simple operation on the walls. It will be a very undulating and flowing space and you’ll get these little glimpses into other parts of the building. You’ll be intrigued, tantalized, seduced.”

Considered to be one of the world’s most innovative and influential architects, Ito has never before designed a building in the United States. His obsession with translucency, dematerialization, and curved organic forms makes him an apt choice for Berkeley’s new museum. He likes ambiguity and blurred distinctions—between inside and outside, up and down, work and play, nature and technology. His best-known building, the Sendai Mediatheque, is a library, gallery, and electronic media center in northern Japan whose seven floors appear to be floating in space, connected only by tubes of steel-lattice columns that look like ropes of seaweed.

Ito is a gentle presence, a slender, slightly stooped man in his mid-60s who listens to questions with an air of acute attention. “I have to tell you the evolution in myself,” he says when asked about his obsession with transparency. “Before, it was a physical transparency, and I used a lot of glass. Recently, the concept has changed. In this museum building, the transparency is realized in the design of fluid space. The inside becomes the outside and the outside becomes the inside without you really noticing it. Different galleries meld and become one. In a space like this, visitors will have an opportunity to come close to each other. Envision a place where transparency is not just a visual effect, but also an emotional and social activity.”

Ito’s design is informed by the vision that the institution’s leaders have for a museum that is not a monument but a process, a place that fosters intellectual inquiry. The curving walls are like the curve of a question mark, asking visitors to respond to the encounters they have within the museum’s walls. Figuring out the unique characteristics of this type of museum, one that both displays art and is art, Consey says, “makes this work both challenging and enormously liberating.” He cites Renzo Piano’s design for the Menil Collection in Houston, Tadao Ando’s design for the Museum of Modern Art in Fort Worth, and Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa’s design for the Glass Pavilion at the Toledo Museum of Art as successful examples.

“There are certain perfect moments in the history of art or in the history of design, when a building strikes exactly the right balance,” Consey observes. “Piano did it in Paris with the Pompidou. Ironically, in the first ten years after opening it was universally considered the most hated building

in Paris. But whenever you innovate, inevitably there’s a period of transition.”

The Centre Georges Pompidou now draws 26,000 daily visitors. Its success can be attributed to many things: the drama of the inside-out building, in which the trusses, ducts, and elevators are on the outside; the glories of its collection; the diversity of its programming (it’s an art museum, a film center, a public library, and a center for new music); and its location next to an attractive open plaza that has become a magnet for street performers. What makes the building exciting is its anti-museumness—instead of being a crypt for preserving the cadavers of high culture, the Pompidou feels like a public square where everything, even the building’s guts, is in the open.

The Berkeley Museum has more modest aspirations, but it too will have diverse offerings in film and visual arts, and if things go according to plan it will also be adjacent to a public square—the newly pedestrianized Center Street. At the heart of Consey’s evocation of the Pompidou is his interest in the same transparency that Ito evokes, in creating a place that is popular not because it shows blockbuster exhibitions or attracts legions of tourists, but because it serves the needs of the community in which it sits—in this case an educated, open-minded lot.

“In a socially engaging and socially active place, you test ideas, push ideas, sometimes even shove ideas,” he says. “It may be that the role of a general-purpose museum is to display works of art and say emphatically, ‘This is art.’ Our job is more to ask the question “Is this art? We think it is, but tell us what you think.'”

That philosophy may be Consey’s, but it is also the guiding spirit of the museum. “Kevin has been the mastermind and the steward of the vision, but I think the vision is very embedded in the organization,” says Jane Metcalfe, co-founder of Wired, who sits on the museum’s board of trustees. “We’ve been excited by how quickly a meme can spread. It’s deep inside the staff DNA at this point.”

The Berkeley Art Museum was founded in 1963 after Hans Hofmann, the abstract expressionist painter who once taught at Berkeley, donated 47 paintings and $250,000 to the university. The museum opened seven years later in a rugged, poured-concrete building designed by modernist architect Mario Ciampi, and was joined almost immediately by the Pacific Film Archive. In the intervening 37 years, both institutions have developed collections that reflect their Pacific Rim location. In addition to modern and contemporary art from California and around the world, the museum has strong holdings in both contemporary and historical Asian art. The film archive has the largest collection of Japanese films outside Japan. But while PFA has developed a solid reputation as a venue for rare and avant-garde films, the art museum has kept a low profile, despite some impressive holdings.

One reason is that Consey has an almost visceral dislike of blockbuster shows. “Buy a catalog, buy a T-shirt, buy a poster, and if you’re a venture capitalist or a hedge-fund manager, buy a work of art,” he says with a sigh. “We instinctively rebel against reducing art or the experience of an art museum to one of the things on your list of a thousand and one things to do before you die.”

Instead, the museum leadership envisions a place where people encounter unfamiliar art from unfamiliar cultures and come away altered by the experience. When I ask Consey about his favorite part of the current museum, he leads me to a lower gallery dominated by a single work of art: a jagged iceberg made of plaster-filled dishwasher drain hoses by Gay Outlaw. The piece sits in front of a plateglass window that reveals a sunny lawn and a footpath traversed by students, and when you visit the piece you feel as if you have been drawn into a space that is secret and private, a world of mysterious black-and-white forms that is separate from the greenery outdoors. It’s an experience I’ve had in nearly all of my favorite museums—the feeling that I have discovered something wonderful.

“It’s a little more rigorous than putting out 50 paintings of Southern California by David Hockney and saying, ‘These are great, these are interesting, these are expensive, and these are important.’ That has real value, but our approach would be to take similar work, integrate it with 18th- and 19th-century American landscapes, compare and contrast it maybe with Chinese or Japanese landscapes, and then have a seminar or symposium explicating the similarities and differences,” Consey says. “And it’s interesting for a museum with a container that will be 21st-century cutting edge, and a collection devoted to the edgiest living artists and filmmaking, to have an interpretation and philosophical mindset that is very old-fashioned.”

This vision of a museum that educates its patrons rather than simply dazzling them is indeed old-fashioned. But then, the very idea of a museum is old-fashioned. Museums as we know them are products of a culture that valued civic life—public buildings, public parks, public institutions, and public gathering places. These days we value home entertainment centers more than theaters, podcasts more than public lectures, gated communities more than public parks. While blockbuster shows continue to break attendance records, smaller museums across the country are struggling to attract visitors, a phenomenon that says less about how much we value art than about how inclined we are to leave our homes to see it.

The new Berkeley Art Museum is thus, in many ways, a throwback to another era. It is part of an attempt to revitalize the civic landscape and encourage people to congregate in public spaces, to get out of their cars, lounge in public parks and plazas, experience films, plays, and works of art in the company of strangers, and in general behave the way urbanites behaved before we spun ourselves such pleasant and separate digital cocoons

“The first question to ask is, when everything is available online and we all have these giant plasma screens in our living rooms, why would you go to an art show?” asks Metcalfe. “And the reason is that people are desperate for the collective, shared experience you can get from a museum.”

Ito notes that his Sendai Mediatheque gets one million visitors a year, in a city with a population of one million—a statistic implying that nearly everyone in the city passes through at least once. Yet when the building was proposed, people wondered whether it was necessary to have a library and gallery in the era of the Internet.

“I’m a strong believer that the more you have tools to work remotely, the more you like to see people face-to-face,” Ito says. “One interesting observation from the staff of the Sendai Mediatheque is that old people there have become very fashionable. They sit next to young people who are keen on fashion, and they get influenced by that. That’s the power of public space.” It’s amusing to imagine Sendai’s geriatric set suddenly sporting the black lipstick and Edwardian bonnets popular among Japan’s goth teens, but Ito’s point is more profound. When you mix people together in a public space, ideas spread across generations and subcultures.

That kind of cross-pollination is exactly what Richard Rinehart, the Berkeley Art Museum’s digital media director, hopes that the new museum can foster. He wants to explode certain museum boundaries in the same way that Ito has exploded the idea of walls. “Why not have digital art in the hallways, have it in the library, have it in the bathroom stalls, which in many ways might be more suitable for it?” Rinehart asks. “It might be much more interesting to have a sound work in a corridor rather than in a gallery, where you’re prepared for it.”

Rinehart imagines the museum as a series of concentric circles radiating out from the gallery, first into the corridors and bathrooms, and then out onto the skin of the building itself. What if, when you walked by the museum, you saw digital art gamboling across the walls? Ito’s design includes two large expanses of glass on the second floor where it faces Oxford Street. One idea is to use glass with opacity that can be controlled, so the glass can serve either as a window or as a screen. By rear-projecting onto that screen, curators could use the building’s skin to display everything from digital art to silent movies.

Extending beyond the building itself would be the museum’s virtual self. Back in 1994, the Berkeley Art Museum was one of the first museums to launch a website and is now in the process of building what it calls the Open Museum, an online collection of digital artworks that will be completely open source. Anyone can download all the files from a piece of digital art—video, source code, Flash files—and copy them, study them, or remix them into new works of art. From a traditional art perspective, it is a startling idea. You can’t exactly imagine inviting museum patrons to make collages from the museum’s paintings, for instance. But in the digital world, it makes perfect sense. “Openness and transparency characterize digital media,” Rinehart explains. “If you’re going to bring the soul of digital media—rather than just the form of digital media—into your museum, you have to be willing to embrace that openness.”

(Rinehart is already embracing it. This year, he invited six artists to remix two digital art pieces from the museum’s collection. The resulting artworks, along with the originals, premiered at a show called RIP.MIX.BURN.BAM.PFA in October and can be downloaded and remixed again here: bampfa.berkeley.edu/ripmixburn.)

In my conversations with Rinehart, Ito, and Consey, a certain image kept recurring, an image of serendipitous discovery. Each of them invoked the new museum as a place where people could have a casual encounter with art, something informal and unplanned. Listening to them, I kept imagining people wandering through the building the way you might wander through a park—not because there is something in particular you are planning to see, but because it’s a park you like, and it’s likely that you’ll encounter something familiar that you want to see again, or something unfamiliar that surprises and intrigues you.

When I say that to Ito, he nods vigorously. “It’s interesting that you say a park, because park has always been the central image I have for my buildings,” he says. “If you have a rigid building, people feel they have to behave in a certain way. I envision my building to be a place like a park, where people come to relax and get inspirations from other people.”

Of course, it’s hard to have people wander into your museum if they have to pay eight bucks at the door. For that reason, Consey is hoping that in the new museum a substantial portion of the galleries will be free, like most museums in London. “That’s how libraries operate,” he says. “If I want to browse through a research book about Turkey, I can do it over five or six visits. If I want to do that at Barnes & Noble, I’d better bring my wallet.”

A free museum invites people to be curious but also casual. Rather than death-marching through gallery after gallery to get your money’s worth of art, you can spend 15 minutes staring at a single painting and then turn around and leave. It invites you to try looking at something you’ve never heard of, and suspect you might not like, because it doesn’t cost a cent. And it opens up the world of art to people who might otherwise never cross the threshold. Brent Benjamin, director of the free-admission Saint Louis Art Museum, recently explained the impact to the contemporary art blog, Modern Art Notes. “I was in the galleries here a few weeks ago and three preteen boys came trouping through with their skateboards,” he said. “They checked them, and then they went down to look at the collection of arms and armor. That’s a museum director’s dream.”

One afternoon over the summer, I asked Consey to walk me through the current building and tell me about its limitations. (The building’s future is still up in the air, but campus officials say they would like to find a new purpose for it after the museum moves downtown.) Many of the things he pointed out were mundane—a too-steep grade on the ramps; a lack of space for teaching or for grabbing lunch. Other concerns were more subtle. When we walked into a gallery that housed David Goldblatt’s large, color photographs of South African townships, Consey pointed out the vast empty space above the pictures. The photographs are meant to dominate the space, but the endless ceilings make this impossible.

From where we stood, the building fanned out in a series of jutting promontories and expanding vistas. It’s a lovely space to be in, but the open floor plan means there’s less wall space for exhibiting. Within its curving lines, the new museum will have regular four-walled rooms, resulting in 25 percent more display space.

But for Consey, the biggest liability of the current building is that it was not designed to foster interaction between film and the other visual arts. The development of connections between them has been one of his major accomplishments, and he would like to see that connection made visible. (“Before he arrived, there was an invisible wall between art and film,” Metcalfe says.) During much of our conversation, we sat in a gallery that displayed photographs by the Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami. These were the stills of winding roads, rain-spattered windshields, and lines of trees that had so struck me in my initial pass through the museum, and they were being exhibited at the same time that the Pacific Film Archive offered a summer-long retrospective of the great director’s work, 26 films in all. The photographs are reminiscent of Kiarostami’s films—many were taken while he scouted locations—but they are not film stills. Yet what is the difference? How is a photograph different from a movie? Why would someone who works in moving images choose to work with discrete images, particularly landscapes? What is behind Kiarostami’s obsession with the view from inside a car? These are questions that might arise spontaneously if the two retrospectives were in the same building.

“You would have a hard time trying to convince some of my colleagues that a film is, in fact, a work of art,” Consey says dryly. “But one can harvest as profound and as interesting and as subtle an aesthetic, moral, and social message from Antonioni’s Blow-up as you can from the Mona Lisa. Art is not something that’s fixed—it’s something that moves as quickly as the hard drive on your laptop.”

Not long afterward, I went to see the 9 p.m. showing of a Kiarostami film, The Wind Will Carry Us, at the PFA. I hadn’t expected many people to show up for the late showing of an obscure movie on a warm weeknight in August, but there were about 100 people in the audience: young women in headscarves speaking Farsi, older couples greeting friends, droopy-eyed college students looking over the program, middle-aged men who had come alone. There was no popcorn or soda in the theater, just soft purple seats. All around me, people were talking about film. I heard fragments: “It was shot in stages …” and “That was the film that influenced…” and “There are many people who go to more films than I do, but I do love serious films.”

The Wind Will Carry Us, though captivating, is difficult to parse. A man visits a village in Iranian Kurdistan, waiting for an old woman to die, but his motives are often oblique, and the end offers no clear resolution. When the lights came up, conversations flared around me as people tried to figure out what had just happened. Clusters of debate ignited like tiny fireworks as people moved from the theater to the street.

“Having a deeper understanding of cultures that seem so alien and disconnected from ours is a valuable service that visual arts institutions can serve,” Consey had told me when I’d asked him about Kiarostami. “In my mind, universities stand for the idea that knowledge means something. And that knowledge leads to understanding.”