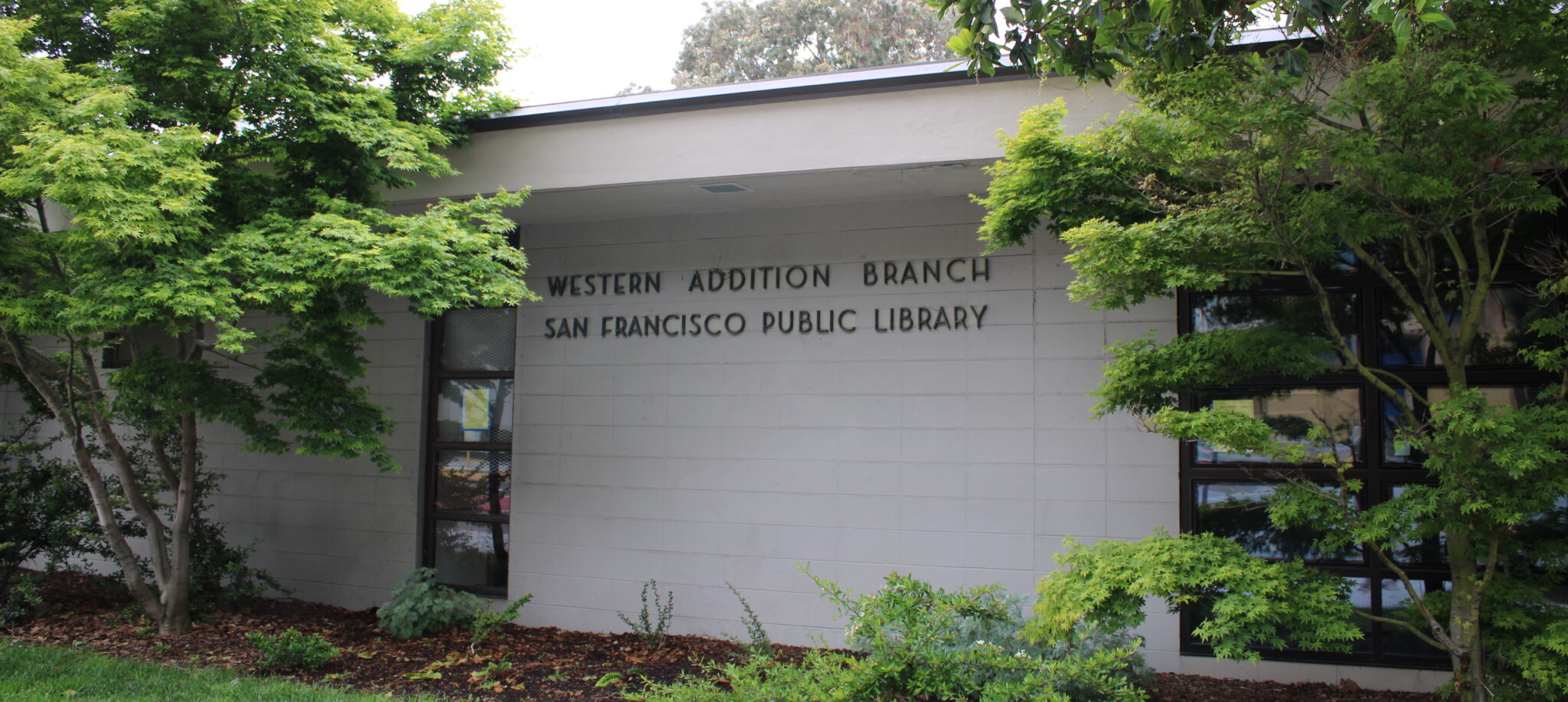

Dorothy Lazard’s first library—the one that cracked open her world and made her love libraries—was the Western Addition Branch in San Francisco. At 10 years old she sat on the floor between the stacks to read The Thin Man, The Autobiography of Malcolm X, The Diary of a Young Girl, and the poetry of Langston Hughes.

Twelve years later, in 1983, she earned a master’s degree at Cal from the School of Library and Information Studies. She was one of two Black students. “The country was looking for more racial minorities to get into library schools, and I was like, I’m that,” she said. Even with a scholarship to boost her morale, she remembers being overwhelmed by the number of people on campus and sitting in her car between classes for most of the first week.

As an adolescent, Lazard read at the library because her grandmother had said no to a library card. Mam’Ella, with whom she lived, didn’t trust book learning. “It was like, ‘Sit down, shut up, stay outta grown folk’s business,’” Lazard quoted her grandmother as saying. In contrast, librarians encouraged Lazard’s curiosity. “I was expected to ask questions,” she said.

Lazard’s older half-sister, Sarah, eventually signed for her library card, and Lazard continued her ravenous consumption of books. Recognizing herself and her family in books written by Maya Angelou and Toni Morrison, Lazard realized that “Black girls could grow up to become writers of books housed in libraries”—and was determined to become one.

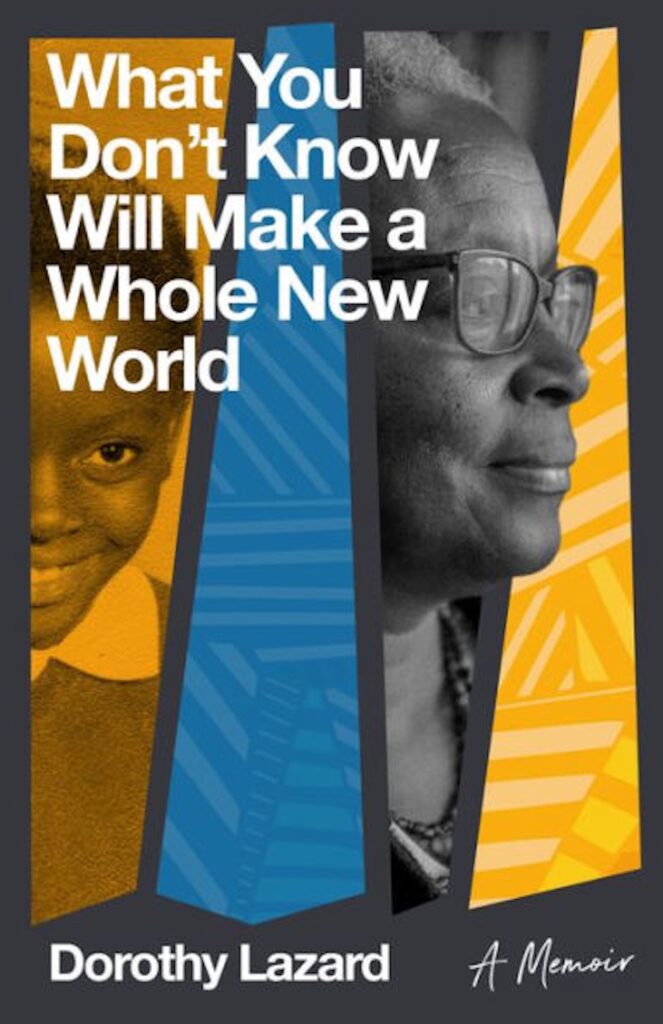

With the publication of her coming-of-age memoir, What You Don’t Know Will Make a Whole New World (Heyday Books, May 16, 2023), Lazard is finally joining the club she first revered as a child.

Spanning her arrival in San Francisco at age 8 to her graduation from Oakland’s Castlemont High School in 1977, Lazard’s memoir is filled with stories about her family, including her beloved mother, Ma’Dear, who suffered from grand mal seizures; teachers both good and cringe worthily bad; and the effervescent presence of Black music played on record players. Black entertainers appearing on television were rare enough that the occurrence brought the kids running inside to watch. The murders of Emmett Till and Martin Luther King Jr. also serve as important touchstones to her story.

Lazard moved to Oakland during the Black cultural revolution in the early 1970s, a time that she refers to in her book as “the first best time to be a Black kid in America.” She fed her eclectic interests at the Oakland Public Library by flipping through glossy magazines, reading fiction with intriguing cover designs, and attending travel talks in the library’s basement. She also discovered James Baldwin and one book in particular: The Fire Next Time. “[His words] made me feel as though the top of my head had been blown off. I had never read such calmly articulated rage and honesty and love,” she wrote in her memoir.

During that time, in the span of just two years, a teenage Lazard lost her father, grandmother, and mother. She was devastated by her mother’s death but fortunately still had her sister, Sarah, who took her to museums, art exhibits, and Black films like Shaft and Lady Sings the Blues. Sarah also bought her a journal to encourage her writing. “Anything I was interested in, she was like, how do we do that?” said Lazard.

Though a writer since age 10, Lazard has spent most of her professional life as a librarian. After graduating from Berkeley, she worked at two different campus libraries for 17 years—first with Counseling and Psychological Services and then Women’s Resources. Both were rewarding, but she worked alone and longed to learn from other librarians.

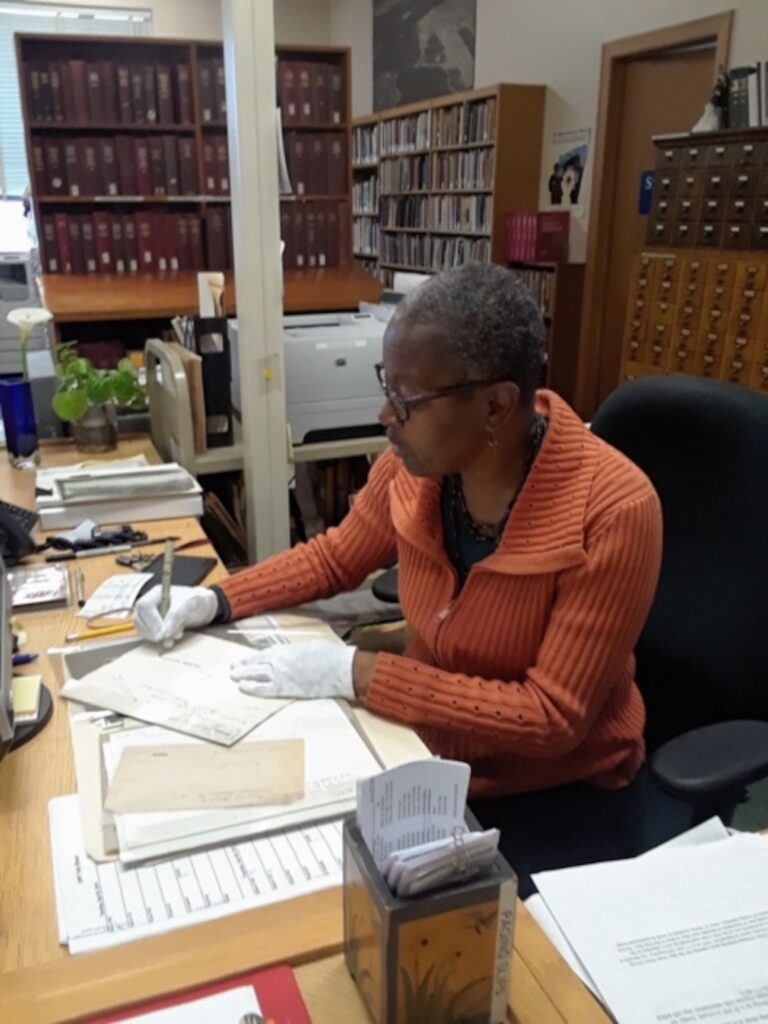

At age 40 she took a job at the main branch of the Oakland Public Library, a return to her teenage roots. For ten years, she was the only Black librarian. “It was a big deal to stand behind the desk like people had stood behind the desk for me,” she said. She eventually became head librarian of the Oakland History Center, a small library within the main branch, where she helped students, researchers, and the curious browser learn about Oakland’s history. She loved her job.

“I felt like I was dancing all the time—in a good way,” she said. “Like this is my jam. I felt worthy, knowledgeable, tireless, and engaged.” In 2021, after 20 years, she decided it was time to leave. “I left a good legacy and saw myself as fitting into a continuum,” she said.

That continuum reaches back to Oakland’s first public librarian, Ina Coolbrith. Like Lazard, Coolbirth migrated to California from St. Louis, Missouri, and dealt with tight budgets, banned books, and patrons seeking warmth. But Lazard’s strongest connection to Coolbrith was in the struggle to write while working full-time. Coolbrith left the library after 20 years and was named California’s first poet laureate in 1915. Lazard, too, left after 20 years to pursue her own writing.

“When you’re in your sixties, whatever you’ve left undone, you need to get crackin’,” Lazard said. On May 15, she is receiving the 2023 Oscar Lewis Award from the Book Club of California. She has three other books in the works.

The 10-year-old Black girl sitting cross-legged in the stacks, determined to write books housed in libraries, would have been proud.