One year ago, Alexander Coward attained, by sheer accident, what so many others have sought without success—a little slice of Internet fame. The UC Berkeley lecturer did so simply by sending an email to his math students. The email’s journey to stardom began when a student posted it to Facebook; then another posted it to Reddit. At some point it got tweeted, and soon the share-frenzy began. Within 48 hours it had crossed that illusive, magical threshold—it had gone viral.

CALIFORNIA Online was the first media site to run a story about it, featuring an interview with Coward and the full text of his email, and the response was overwhelming—literally; it choked our newly launched website to a standstill, and would go on to draw more than half a million page views.

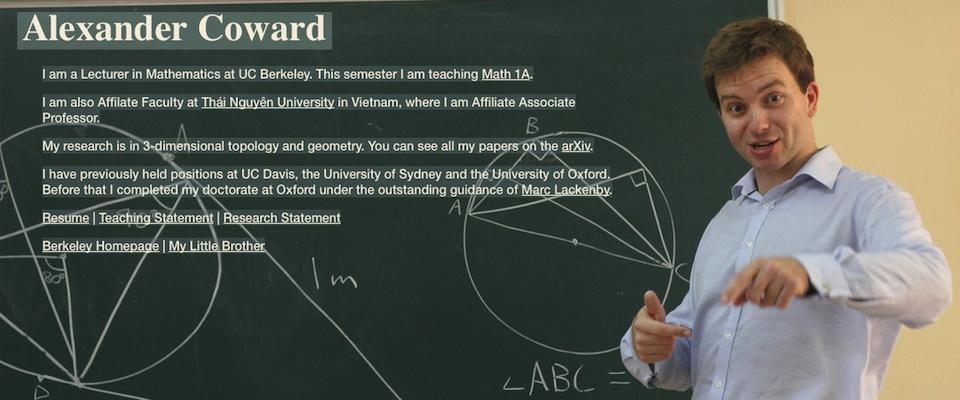

Clearly this wasn’t just any old email, and Alexander Coward isn’t just any old math teacher. A little context:

On Monday November 18th, 2013, the University of California Student-Workers Union announced it would be joining a system-wide one-day strike that Wednesday. Though the UC Student-Worker Union was in the midst of its own contract negotiations with the University, this was to be a sympathy strike with UC’s largest labor union. Two graduate student instructors (GSIs) for Coward’s math classes opted to strike, leaving three sections teacherless. Coward’s email, sent Tuesday night to his 800 students, stated that he would not be striking—thus crossing the picket line—and that he would cover the three sections vacated by the striking GSIs. But Coward did not end his message there; what followed was a more than 2,000-word philosophical missive on the urgency of a college education.

“In order to navigate the increasing complexity of the 21st century you need a world class education,” he wrote, “and thankfully you have the opportunity to get one. I don’t just mean the education you get in class, but I mean the education you get in everything you do, every book you read, every conversation you have, every thought you think. You need to optimize your life for learning. You need to live and breath [sic] your education. You need to be *obsessed* with your education.” He went on to gush with praise and admiration for his students, and posit them as the world-changers (saviors even) of tomorrow.

The message struck a nerve, and social media did the rest. Soon the email was being translated into Mandarin, Portuguese, Greek and more.

“My inbox was just exploding,” Coward recalls. “Dozens of messages from people all over the world” telling him that he was an inspiration.

“Let’s call it what it is. He was a scab….No matter how eloquently he tried to explain his position, you can’t get around the fact of what his actions were.”

Countless readers were struck by Coward’s obvious passion for education and caring for his students, labeling his email “awesome” and “moving.” Some expressed a desire to have such a committed teacher, while others marveled that a numbers guy would have such a way with words. One simply wrote: “Nail. Head.”

But not everyone reacted positively. He received numerous angry emails—“Let’s politely describe them as mean,” he says. Many comments on the CALIFORNIA article, and in a follow-up story we posted after our site traffic had dwindled to a mere 1,000 an hour, excoriated the email as promoting self-interest and discouraging political engagement.

“Ugh,” wrote one, “the degree of condescension and quantity of moralizing platitudes (“You youngsters are just so inexperienced!”) made his email difficult to read.” The comment went on to argue that by ignoring the budget cuts that created conditions leading to the strike, the lecturer was ironically harming his students’ education in the long run.

Though Coward’s email did not address labor politics or the merits of the strike directly, many felt it was an assault on everything organized labor stood for. An open letter rebutting the email by a UC Berkeley Student-Workers Union-member began its own journey around the Internet. The author Michal Olszewski wrote: “From what I can gather, your argument is that we live in a world of developing technology and as students at UCB are part of an elite and exceptional group; therefore we don’t have to worry about the society we live in. I cannot condone this argument. In fact, I find it extremely disturbing that as a professor you are encouraging your students to embrace egoism and to focus on their own education and merit rather than be socially conscious human beings.”

For union members, it wasn’t just the email they objected to, but also Coward’s actions.

“Let’s call it what it is. He was a scab,” Erik Green, the financial secretary for the statewide executive board of the UC Student-Worker’s Union, said recently. “That’s what he was doing; replacing the labor of striking workers. No matter how eloquently he tried to explain his position, you can’t get around the fact of what his actions were.”

Coward recalls that his dispatch was no spur-of-the-moment rant. He says it took him 12 hours to write and represented years of thought about education.

Green, currently a GSI at UC Santa Cruz, was active during the November 2013 strike. He took issue with Coward’s email on the grounds that it encouraged students to “value (their) own individualistic concerns over the collective concerns of the university community.

“The idea of a public university is that we’re working for the quality of education,” he said. “Sacrificing a day or a couple of days in order to improve the quality for yourself and for the future generations is really something undergraduates should be a part of.”

Today, sitting at Saul’s Deli—the very restaurant where the 32-year-old composed much of the infamous email—Coward recalls that his dispatch was no spur-of-the-moment rant. He says it took him 12 hours to write and represented years of thought about education.

“I used to be obsessed with mathematics and thought about math all day,” Coward says. “But now I’m obsessed with education and think about teaching—really—all day long.”

“Yeah,” he adds, “I’m a little obsessive.”

Coward speaks in energetic bursts followed by lengthy (sometimes minutes-long) brooding pauses. He explains that there was a time when this new fixation caused him some guilt. “It’s a funny thing to say,” he says, “but I felt like I ought to be thinking about research more, not spending all my time thinking about teaching. But I just love teaching. I absolutely love it.”

Coward grew up in London. His father is a mystery novelist, perhaps explaining his son’s facility with words. The son is currently pursuing a distance-learning master’s degree in teacher education from Oxford, where he earned his Ph.D. That he is passionate about education is obvious; the conversation, much like his viral email, consistently veers toward his teaching philosophy.

“The number one most important quality in being a good teacher is caring about your students,” he says. And he adds that it was his enthusiasm for education, rather than politics, that compelled him to take over the sections of the striking GSIs: “I wasn’t trying to make a statement about the strike. I just thought, ‘Oh, there’s a classroom full of my students. That sounds fun!’ ”

If that seems implausible, know that Coward’s favorite thing to do on vacation is teach. This summer, he did so in the European Innovation Academy and mentored students for Berkeley Summer Abroad. He spent his previous vacation teaching in Vietnam. “This is what I do for fun.”

After a little prodding, he admitted that there was more to the decision to cover the sections than simply joy-seeking.

“Ok, so maybe I was looking at the big picture,” he said. “ I think there is something incredibly urgent going on in the classrooms in places like Berkeley. I feel offended by the sentiment that (one day of class) doesn’t matter so much. Not turning up to class when your students are there is saying, ‘This other thing is more important.’”

“It’s true I don’t get paid as much as a professor with a capital ‘P’, but there’s this general phenomenon that people who do things because they love it, particularly things that are caring, end up getting paid less. I get paid in all sorts of other ways.

He seems to view education as a sort of magic cape that, once donned, leaves the wearer practically invincible. In a video clip recently uploaded to youtube by one of his students, Coward tells a packed classroom that “getting an education is sort of like grabbing one of those magic stars” in the video game Super Mario Bros. “You can run through obstacles and barriers and difficulties which you just can’t if you don’t have a good education. And nobody can take that away from you. … It’s yours,” he says, earning enthusiastic applause. The video is at 2,369 views as of this writing—not quite viral status, yet.

Asked how it felt to be called a scab, Coward is silent for quite a while, reflecting. “I think it was good. It’s good to be reminded that there are multiple sides to a story. The strike was about people working hard under difficult circumstances and wanting to be treated fairly.”

When Coward cites “people working hard,” he isn’t referring to himself, but Green and other vocal union advocates believe that union efforts ultimately are about benefitting all university employees, lecturers included.

“A really ironic part is that (Coward) is not a professor, he’s a lecturer. So he’s actually an extremely exploited class,” said Green. “Lecturers make significantly less than professors. Him out of anyone should be completely on the frontline and advocating for people to get decent wages.”

Coward bristles at the notion. “I get to get up every morning and do something I absolutely love. I feel privileged to do what I do,” he says. “It’s true I don’t get paid as much as a professor with a capital ‘P’, but there’s this general phenomenon that people who do things because they love it, particularly things that are caring, end up getting paid less. I get paid in all sorts of other ways. My job is to hang out with undergraduates and teach them stuff—and it’s really fun.”

From an organized labor perspective, this is a highly problematic view. And Coward admits to being uninformed about labor politics.

“I know what my priorities are, but I don’t know for certainty that I was right. I’m not an expert in industrial relations in the U.S.”

Asked what he’d do differently if he had the whole thing to do over, Coward says “I might have added a few softening words” to the email.

Then he adds, smiling, “And I would have spelled ‘breathe’ correctly.”