For 45 minutes, on July 28, if you happened to be at the border between Sunland Park, New Mexico and Ciudad Juarez, you’d come across something surprising: a hot pink seesaw.

The man behind the installation, UC Berkeley Architecture department chair and professor Ronald Rael, has long used his work to create conversations about the U.S.-Mexico border wall. He’s examined these ideas in his book Borderwall as Architecture (UC Press 2017) and, most recently, through his large-scale art project, the “Teeter Totter Wall.”

Originally conceived of in 2009, the Teeter Totter Wall represents Rael’s latest work in reshaping perceptions of border communities. Late last month, the project was realized when Rael carried three pink metal beams and stuck them between the slats of the wall. “We drove up, and the border patrol asked us what we were doing. We told them we were setting up a teeter totter event for children.” For the next hour, border patrol watched on as families from both sides of the border played on the seesaws. “I think that these spaces need to be recognized as spaces of humanity,” Rael says. “And the wall is problematic in those spaces of humanity.”

The seesaw wall was just one of many ideas that Rael and his design partner, San Jose State University professor Virginia San Fratello, conceived in their thinking about how to recognize the contradictions of these spaces as both sites of state violence and as home to many people. Working in partnership with Juarez-based social-design collective Colectivo Chopeke, Rael and San Fratello ultimately chose this design both for its whimsy and its symbolism. “The notion of play has become an even more pressing topic because of child separation.”

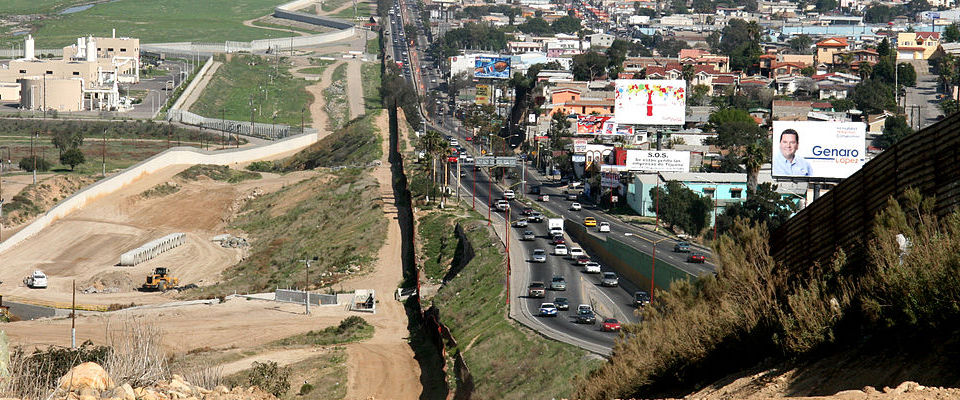

Rael is interested in the ways that artists and communities can dismantle the wall—if not literally, then with design that both uses and disempowers it. And after the 2016 election, the work became even more urgent. “[When] a candidate stands before people and announces that he is going to build a wall when there’s 700 miles already in place, that demonstrates a national ignorance that a wall doesn’t exist. My work exposes not only the existence of the wall, but the problematics of the wall.”

Rael, who was raised in Colorado, explained that perceptions of the border are often shaped by those who don’t live or have roots there. “I am a person of color. I am an Indigenous person to New Mexico and Colorado and Mexico. My own history is that landscape.”

“Architecture serves as an agent for change, and the education of architects is very idealistic.”

His place in commenting on that landscape was called into question by early critics who accused him of trivializing the suffering at the border by bringing in objects of joy and play. “The way we look at these landscapes is often through the white gaze. And so what one expects to see are poor people suffering, [people who] don’t have the capacity for joy because no one has gifted them with joy. But instead what this project does is simply demonstrate that mothers and children, with small sticks, can render impotent this giant, expensive piece of construction.” The symbolism of the see-saw also played a role in the choice, Rael explains. “[It] is the perfect metaphor for this kind of balance and imbalance that we’re constantly going through.”

Even the color of the see-saws served as a statement. The project’s vivid pink was in recognition of another important issue affecting the border, that of the murdered women of Ciudad Juarez. “We wanted it to be fun, but also recognize that this is a project that combines horror with joy. That color in Juarez is well-known as signifying women who’ve been killed in the femicide. We recognized that it is a place of violence.”

The project was even more poignant with the recent shootings in El Paso—a city that borders the project site. And Rael, who identifies as “a product of the border land,” feels this connection personally. “We don’t often recognize the moments of joy that are concurrent with the continued gun violence,” he says. “This is the fundamental dichotomy. I talked to a lot of friends after this happened and they made me recognize that these kinds of shootings have been going on for a long time, and that we should continue to pursue spaces, and moments, and events of joy, and we should do something about the continuing violence taking place.”

For Rael, architecture is a tool for activism. It can not only challenge assumptions, but it can speak to concerns about ecological impact, and raise questions about how infrastructure can impact communities. “Architecture serves as an agent for change, and the education of architects is very idealistic.” It’s important, he notes, to teach students the responsibilities of the field, and that they are building for people. “I would like to think that it should be inherent in the profession that architecture is activism.”

In the weeks since the installation, the project has opened up conversations about the U.S.-Mexico border, with Rael receiving support for his work from as far away as India, Taiwan, and Japan. It has also prompted others to create their own works disempowering the wall, including a group that attached basketball hoops to the wall citing Rael’s project as inspiration. The global response is particularly impressive considering that the teeter-totter only lasted 45 minutes.

Rael considers the project a success because though short-lived, it challenged people’s perceptions of the border and of those who call it home. “I think there’s a public reading that these spaces are off limits to the populace, that these spaces are dangerous, that these spaces are no man’s land. And part of this project is to demonstrate that, no, these are places where people live. This is something that you could touch, something tangible and real; you can shake hands across the border. These are public lands. These are communities. These are wilderness areas. These are farms and private property. This is not some kind of middle of nowhere frontier.”