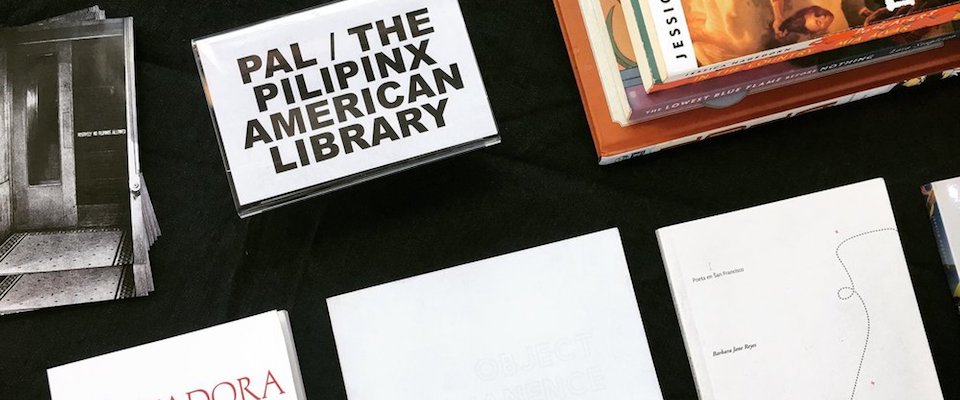

As a successful, Filipina-American, experimental feminist poet, Barbara Jane Reyes is something unusual. Her poetry, which she describes as “Filipina affirming work, Filipina centric work, in which the definition of Filipina must be complex and manifold,” is being featured at the San Francisco Asian Art Museum, through the month of August. She joins poet Al Robles as part of the Pilipinx American Library, a non-circulating library in the museum’s Resource Room. Filled with shelves and tables of books by Filipino Americans, not to mention beanbag chairs for lounging, the library offers a space to experience text through communal readings, workshops, and performances. While such events create an important community for Filipinos and non-Filipinos alike, Reyes reminds readers that her poetry doesn’t need a platform to exist. “I am not your ethnic spectacle,” she asserts in her most recent poetry collection, Invocation to Daughters. “I write whether or not you invite my words.”

The author of five books of poetry including Invocation, a finalist for the 2018 California Book Award, Reyes came to California from Manila when she was 2 years old and grew up in the Bay Area. At UC Berkeley, where Reyes planned to study English, she gravitated to works by female icons Toni Morrison, Audre Lorde, and Cal Professor Emerita Maxine Hong Kingston. Reyes ultimately completed her degree in Ethnic Studies while getting involved in the Kearny Street Workshop, where she found support for her work among the “literary elders” of the Asian Pacific American community. Now Reyes, who teaches Filipino literature at University of San Francisco, is returning the favor and mentoring a new generation of young Filipina writers.

Recently, Reyes sat down with us to talk about the importance of the library, growing attention to Filipino culture in the Bay Area, and Filipina author Jessica Hagedorn, whose award-winning novel Dogeaters convinced Reyes to be a writer.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

When did you decide you wanted to be a poet?

I had always been writing. I don’t know if I was conscious it was poetry I was gravitating towards until other writers pointed it out to me. Maybe in college, I was told, “Oh, wow, so you’re a poet then.” But that was because I had a tendency toward lines that did sound like poetry. I read William Blake and went to City Lights Books when I was in high school. But I had always been writing. I remember a fictionist said to me when I had written a short story, “Oh, so you write fiction as well.” That was the first time it dawned on me a writer chooses a genre. (Laughs.)

Did you feel like your family or society gave you the message you weren’t supposed to be a writer?

One thing about coming from an immigrant family, which was common to so many of my friends from different backgrounds, was our parents really wanted us to go to college and get sensible degrees and do something prestigious. So being a writer here, nobody knew what to do with that. And when folks in my extended family ask what I do—especially when I was still emerging—they would be like, “Oh, you’re a writer,” and give me this look like, “I don’t know what to do with that.”

But going back to the Philippines, when I say to people, “I’m a writer,” or “I’m a poet,” that means something to them. Here I don’t know if we know what poets do. In the Philippines, our national hero was a poet [José Rizal], so maybe that’s why we have this idea, “Oh, I know what a poet does.” Even if it is an archaic image of somebody who rhymes or writes with a quill.

Do you think Filipino culture is getting more attention lately?

I think it’s one generation building upon the next. We have a generation of folks who are now established in academia, and the pulse of what we’re doing in the arts comes from community—and maybe being anchored in universities gives it validity. I think one thing so many of us have learned is this kind of indie, DIY ethic. Toni Morrison said that about writing The Bluest Eye, if you don’t see the book in the world you want to read, you better write it yourself. Prior to [musician] Rocky Rivera becoming Rocky Rivera, there probably weren’t that many Filipinas in hip hop, and if not for Rocky Rivera, maybe Ruby Ibarra wouldn’t have come so quickly.

I could complain for a very long time that there are no Filipina-authored books of poetry out in the world, or I can write like hell and be real aggressive about publishing. If there are a few of us doing that, pretty soon you have a presence. I do feel a tremendous sense of responsibility, not in such a way that if I don’t do it, I’m going to get slapped on the wrist by my grandma, but this is a way of paying it forward. Whether Jessica Hagedorn knows it or not, if not for her, I would have never thought I could do this seriously. I’d still be writing in my private notebooks.

What’s your favorite place to eat Filipino food?

The Lumpia Company—they have a window at the Kitchener in Uptown Oakland, and if you follow them on Instagram, you’ll see what kind of lumpia they’re making.

They have non-traditional kinds—bacon cheeseburger lumpia is my favorite. It doesn’t sound like it would work, but it does. I think that’s what I like about it—it’s not conventional. They do a lot of unconventional things like pastrami and asiago. I guess it’s very Filipino American in taking something very familiar and twisting it around.

When we’re trying to grapple with the authenticity question—it comes up at every single Filipino book festival I’m at. Someone will always ask me questions about how authentic my work is, and I feel like this is my answer. What part of the Philippines am I from? I’m from Fremont. And what does that mean? It means my Tagalog is messed up, that I speak more Oakland than Tagalog. It means when I’m making a traditional dish, my ingredients come from Trader Joe’s or Whole Foods. So these things change, not because I’m giving Filipino culture my middle finger, but it’s just what’s here and around me.

In a blog post you wrote about the Pilipinx American Library at the Asian Art Museum, you mention how much Jessica Hagedorn meant to you. Could you talk about that?

In 1990, a woman who was a local educator told me about Jessica Hagedorn. Up to that point the only Filipino-authored book I’d ever read was Carlos Bulosan’s America Is in the Heart. But Jessica Hagedorn was like, oh, my gosh. She was a teenager who was hanging out in North Beach, writing this kind of rough- edged poetry, her voice was similar to mine and Ntozake Shange’s for colored girls, and that was what I was getting into at the time. I was afraid of writing that kind of poetry that wasn’t traditional. I didn’t know that anybody would ever take it seriously and that it would be anything more than thoughts in my own private journal.

Just to see this language, especially colloquialisms and swearing and the way people interacted with one another was pretty familiar and weird to see in a book that was getting so much attention outside of Filipinos. That was a big light bulb: if this girl who was a scrappy Filipina teenager in San Francisco could do this thing, there’s no reason why I couldn’t pursue writing as well. I think a whole generation of us tried for a long time to be Jessica Hagedorn. It produced a lot of what I would call my proto-poetry—like I can do this, I can swear and use curse words and ampersands and lower case.

I don’t do that so much anymore, omit punctuation or capitalization because I need to stress proper nouns and authority of certain figures in the poems, and I need the pacing which punctuation affords. But when I was actively omitting punctuation and capitalization, my poetry was fast-speaking, breathless, urgent in tone. It took those proper names and flattened them out.

When you write, what do you start with—a word or an image or idea?

These days, I start writing a new poem or new series of poems, using my previous work as a launching platform. What speck or germ from that, what aspect did I want to excavate further? These days, I’m super focused on my speakers—Filipina ones—deep in their own worlds, which define them in certain narrow ways. My speakers resist those definitions and assert themselves and their complexities. The verse comes from my speakers’ self-assertion; the music becomes persistent, even aggressive because the message necessitates that. The sentences become very subject-focused. The poetic lines are longer because her interior life is rich.

How did you get involved with Kearny Street Workshop?

In the 90s at UC Berkeley, I was with a publication, Maganda. I was writing poetry and helping edit the magazine, and we connected to Kearny Street. We were seeing more of these books written by Fil-Ams, and with the book releases there were always parties. Jaime Jacinto was having a party South of Market at 330 Ritch and asked me if I would read a poem. I was like, “Hell yeah, oh my god!” I didn’t know necessarily what was happening in the rest of the country, but I knew in the Bay Area, Kearny Street was there. Al Robles would come to events and talk about, “You youngbloods are the future,” and I was like, “Oh, my God, I’m one of the youngbloods, yay!” He had so much enthusiasm, and he was so excited to see young people writing and caring about writing and about our communities.

I hate calling them elders, cause it’s not like they’re old, but literary elders. I always had that, and it’s really a blessing. They were interested in what we were doing, and maybe they didn’t set out to become mentors but definitely their presence and the fact they included us really meant something. I don’t know if I could’ve gotten that anywhere else.

Do you mentor people now?

There’s a Tagalog word, “ate” that means elder sister. I teach a Filipino and a Filipina Lit class at USF, and a lot of young women take my class, and the next thing you know I’m their ate.

Outside of that there are younger writers in the community who have informally come to me to get connected and learn what’s going on and to tell me they’ve read my work and that’s inspired them. Recently Kearny Street took part in Litquake, and I saw a young writer there, Rachelle Cruz, I remember she was reading these wonderful poems, and one of them was about a New York fire hydrant. I bought her chapbook and Google searched her, and I told her, I think your stuff is really, really good. A few years later when Rachelle’s book was accepted by a press, she asked me to write the intro and I was so moved. Her book, God’s Will for Monsters, just won the American Book Award.

Why do you think something like the Pilipinx American Library is important?

What struck me about seeing people in the space was how folks were sitting in the beanbags and reading or looking at bookshelves and picking something up and sharing with a friend. At the opening, there were so many people just looking through stuff, and in a public space to have reflection and the ability to think and read and share with one another what you’re feeling, is wonderful. Every other year at the San Francisco Public Library, there’s a Filipino-American international book festival, and there are great readings and events. But there’s very little room for thoughtfulness because it’s a literal marketplace, and people are rushing from one event to the next, and you can’t have a conversation.

So that’s the key for me. At the library you can have the experience with the books, talk to a writer if they’re there, and then you can have your own experience as well. In Filipino [culture], we tend to be very communal and share everything we do, and reading is a solitary activity. So how do you put them together so it isn’t just about consumption?