The rapid fire train wreck-a-day strategy of the Trump administration has left some people breathless and others queasy. Flogging a travel ban designed to exclude Muslims, provoking China, insulting Australia, staring down Iran, comparing Russia to the United States, and locally, floating a question of pulling federal funding from Cal due to inadequate “free speech protections” for far-right pundit Milo Yiannopoulos—whew. It’s enough to leave you wondering who or what’s on first.

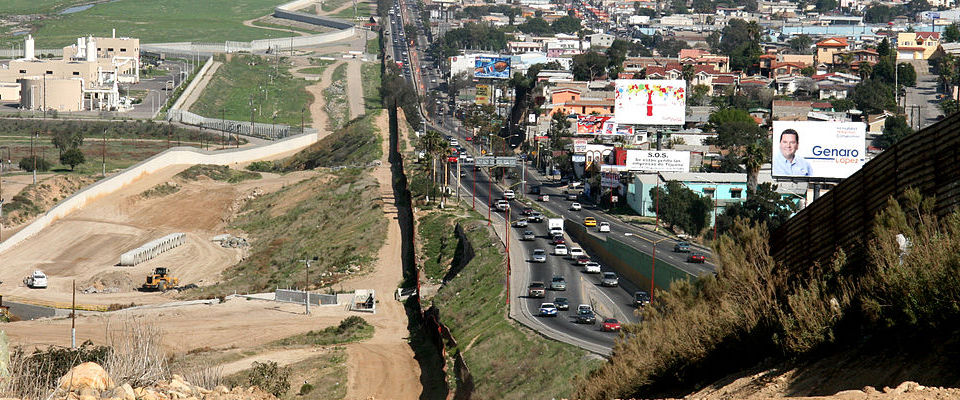

But Trump seems a man committed to keeping his campaign promises, no matter how extreme. And lest anyone forget, his central promise was a “beautiful” wall on the southern border of the U.S.

Mexican president Enrique Pena Nieto recently gave his American counterpart the diplomatic equivalent of a raspberry over Trump’s demands that Mexico pay for the wall, but that hasn’t stopped the new POTUS from pushing ahead with the project. And so far, at least, Republican legislators are going along with the scheme, with Speaker of the House Paul Ryan announcing that Congress, or rather, American taxpayers, will foot the $12 to $15 billion bill (and that’s the minimum: some estimates are as high as $25 billion).

But a “You go, boy!” from Ryan is hardly sufficient to build the forty-foot high, 1,300-mile-long barrier Trump envisions. There’s a lot of resistance to the proposal, including from some members of Trump’s own party. And then there’s the law. A project the scope of the wall naturally raises a host of environmental and eminent domain issues. The scheme could be fatally hamstrung by the massive inertia enforced by the American legal system before a single post is sunk, cubic yard of concrete poured, or strand of concertina wire strung.

Or maybe not. Trump, apparently, is relying on the force of the Secure Fence Act of 2006 to erect the wall. That statute would allow the administration to waive the federal Endangered Species Act and the National Environmental Protection Act—both potent environmental laws that have stopped many an ambitious project—if the Secretary of Homeland Security deems a wall “necessary and appropriate” for a safe and secure border.

But as noted in a New York Times op-ed penned by University of Chicago Law School professors Daniel Hemel, Jonathan Masur and Eric Posner, the wall could be undone by a 2015 Supreme Court opinion. Michigan v Environmental Protection Agency was written by the late conservative legal lion Antonin Scalia, and required the U.S. Environmental protection Agency to consider the costs of proposed rules limiting mercury emissions from power plants.

That decision could now be used to put the kibosh on the wall, if it can be successfully argued in the courts that the costs of the wall, financial, environmental, and social, outweigh the benefits.

“The wall would cost a lot, and its benefits are unclear, but the Secure Fence Act does give the administration pretty broad powers to dispense with legal requirements such as NEPA.”

“Michigan v EPA is very interesting in that it’s a political barrier Republicans have used in demanding that specific legislative actions pass a cost-benefit test,” says Holly Doremus, a UC Berkeley Law professor and a co-faculty director for the university’s Center for Law, Energy & the Environment. “It’s doubtful that a border wall could pass such a test.”

But Cal law professor and Center for Law, Energy & the Environment co-faculty director Daniel Farber isn’t so sure Michigan v EPA could stymie a Trumpian triumph of the will (and wall).

“[Invoking Michigan v EPA] is a clever idea,” Farber says. “The wall would cost a lot, and its benefits are unclear, but the Secure Fence Act does give the administration pretty broad powers to dispense with legal requirements such as NEPA. I’d love to see it stopped, but it may be difficult.”

Doremus says disputes over eminent domain—the right of the government to seize private land for essential projects—could come into play, especially in Texas.

“There’s not a lot of existing border fencing in Texas, so the wall would have to pass through a lot of private land where barriers haven’t been much of an issue until now,” she says. “And certainly, eminent domain seizures are not popular with Republicans in general and Texas Republicans in particular.”

Further, observes Doremus, the Texas-Mexico border is defined by the Rio Grande River. That means that the wall will have to be set back from the river and built on land on the U.S. side.

“That raises not only eminent domain issues, but access to the river and water,” says Doremus. “That could be a significant problem for the many farmers who operate along the border.”

But the biggest stumbling block might end up being that multi-billion dollar price tag. In the guns or butter debate, Republicans generally are lavish in their spending only on national defense. And while the wall is definitely more gun-like than buttery, it isn’t a hard military asset like a cool new anti-ballistic missile defense system or new aircraft carrier. Plus, as noted, many Republicans, particularly from the border states, are queasy about a project that can be easily construed as racist in motivation.

“It’s really expensive,” observes Bill Falik, a lecturer at Berkeley Law and a real estate developer, “and I’m not completely sure at this point that a Republican congress is going to be anxious to go along with that.”

Nor is Falik convinced that federal statutes such as the Endangered Species Act and NEPA would suddenly turn the project into smoldering rubble; rather, they might inflict the death of a thousand torts.

“You have to assume that plaintiffs such as the Center for Biological Diversity, the Natural Resources Defense Council, and the Sierra Club are going to move for restraining orders,” says Falik. “And if that happens, the government will likely try to move forward, claiming the Secure Fence Act gives them the authority to waive NEPA and the ESA. But the administration will have to show reasonable cause for the waivers, and that means proving legitimate threats to national security. That may be a big hurdle to overcome. And if those cases go from federal district court, to federal appeals court, to the U.S. Supreme Court—well, the administration may ask for expedited review, but it could still take time.”

And time could prove the Achilles heel for the wall. The project will always remain deeply divisive, and given the volatility of the Trump administration to date, support even among Republicans could dissipate as the months, controversies, and protests drag on.

“They’re more or less onboard for now,” Falik says of Republican lawmakers, “but it’s by no means clear that’s going to last.”