Amethyst, rose quartz, garnets, pearls…kidney stones? That’s right—it might just be time to add a lesser known formation to the list of gemstones you might want for your engagement ring. Turns out, those uncharming urinary deposits that affect more than ten percent of people across the globe are surprisingly interesting, beneath their rough exterior.

A new study led by former UC Berkeley postdoc and current geology and microbiology professor at the University of Illinois, Bruce Fouke, found that kidney stones, like similar deposits in coral reefs or hot springs, are made of calcium-rich layers that partially dissolve and regrow as they form—disproving years of accepted medical knowledge.

“When doctors find that ugly, boring lump and discard it, they are throwing away the most precise record book we have—a minute-by-minute, layered history of the kidney’s physiology,” Fouke told The New York Times.

Fouke has looked at rocks of all types but says he hasn’t ever seen anything as complex as the layering in kidney stones.

“Virtually every sedimentary or paleontological rock deposit that I have ever looked at grows and dissolves—thus every stone has a history recorded in its layers,” he said. “Applying geological principles to kidney stones has immediately shown that they are dynamically and repeatedly growing and dissolving mineral deposits.”

“You actually go from thin layers to these great, big—I know it’s weird to use this word—beautiful crystals.”

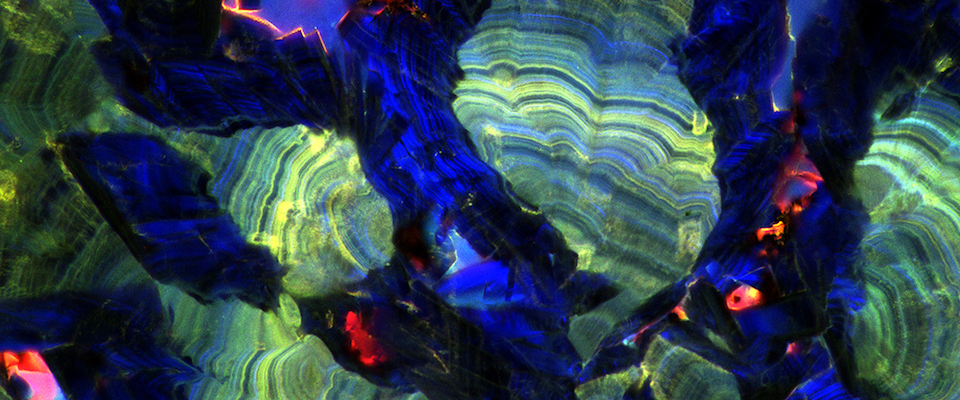

The organic matter trapped and entombed within the calcium oxalate is made up of cell debris, biomolecules, and extracellular molecules (such as mucus). This matter interacts with the ultraviolet, blue, and green laser light from a confocal microscope, creating the spectrum of vibrant colors on display.

You might ask, what possessed Fouke to look beneath the surface of a kidney stone? Said Fouke, “I study biomineralization in a wide variety of natural environments. I had therefore long thought about kidney stones but never had a chance to study them.” He added that his time as a geology postdoc with Berkeley Professor Walter Alvarez was the catalyst that eventually led him to his current work on kidney stones with the Mayo Clinic.

It’s long been believed that dissolving kidney stones couldn’t be done; while home remedies like apple cider vinegar or lemon juice claim some success, medical professionals are taught that only a small subset of kidney stones—uric acid stones—show any effect. Fouke, on the other hand, who had studied rock deposits in other environments, didn’t buy it, and he set out to prove them wrong.

With seed money from the Mayo-Illinois Alliance, Fouke began his research. In a lucky turn of fate, the O’Hare International Airport in Chicago had on display microscope images featuring the mineralization of kidney stones, coral reefs, hot springs, oil fields, and Roman aqueducts. These caught the eye of the president of Carl Zeiss Microscopes, James Sharp, who reached out to Fouke and his team and offered them use of some new microscope configurations for beta testing.

For the first time, Fouke used extremely high resolution (100 nm) microscopes to slice into and examine the stones, which revealed that his hypothesis was correct: each stone has an intricate, and astonishingly colorful, history recorded in its layers. By shining ultraviolet light on the cross-sections of the kidney stones, “You actually go from thin layers to these great, big—I know it’s weird to use this word—beautiful crystals,” Fouke told ScienceNews.

Any plans to give up his science career to start an Etsy shop specializing in kidney stone jewelry? “You’re not the first person to ask!” Fouke laughed. “I had a woman ask if we made any scarves with these patterns yet. But they are really beautiful huh?”