When 24-year-old Hildegarde Flanner and her mother first noticed the scent of smoke coming down from the eucalyptus groves on the hills above their home in Berkeley on September 17, 1923, they watched it with curiosity, rather than fear. But less than an hour later, the darkening plume forced them out. Fleeing to San Francisco by ferry, they saw the city of Berkeley swept up in a “writhing mass of flame,” Flanner wrote. When they returned a couple days later, all that was left of their house was a pile of white ashes and a small piece of Flanner’s grandmother’s shawl.

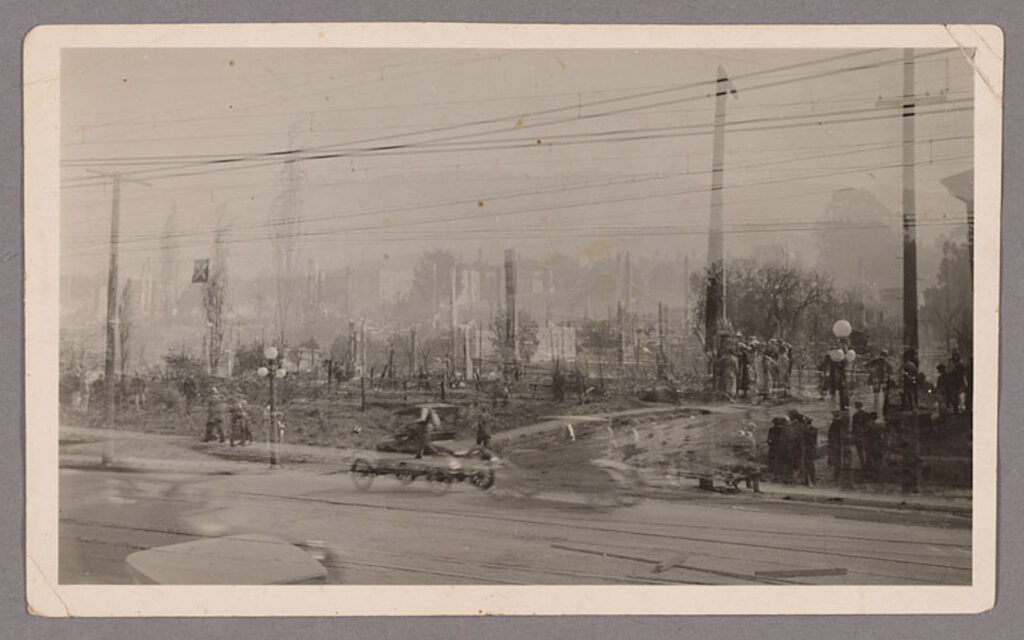

At the time, people were certainly aware that whole cities could burn down. The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 had killed 300 people and left 100,000 homeless. Seattle burned to the ground in 1889. In 1904, the Great Baltimore Fire leveled 1,500 buildings, clearing out much of central Baltimore. And, of course, the San Francisco earthquake of 1906 had spawned fires that razed most of the city, sending refugees fleeing to places like Berkeley to settle in the aftermath. The 1923 Berkeley Fire was similarly ruinous, destroying 500 homes in North Berkeley and leaving 4,000 people homeless.

Memories faded quickly. “I have often wondered why there seem to be so few people who remember the historic Berkeley fire of 51 years ago in which, in two hours time, 60 entire city blocks rose to the sky in smoke,” Flanner, later a poet and an author, wrote in a 1974 remembrance for The New Yorker.

Now, 100 years later, no one is alive to remember the historic blaze and few are even aware of its occurrence. Since then, fire fighting and building safety have improved significantly. The Baltimore conflagration inspired the standardization of firefighting equipment, specifically fire hydrants and hoses. Cities changed building materials and codes, and increased inspections, all of which greatly decreased the chances that a fire could level a whole town or city. For a time, people were able to forget the devastation that wildfire could wreak.

Until recently.

Disasters like Paradise Camp Fire in 2018 and the 2023 fire in Lahaina are stark indicators that fire catastrophes are not a thing of the past. The East Bay is hardly immune: In 1991, the Tunnel Fire tore through the Oakland Hills, killing 25 people and destroying 3,000 houses. Since then, Berkeley has made some improvements to its high fire risk areas, but not a lot, and many experts think it’s just a matter of time before another major fire happens in Berkeley.

“What we’re facing now is different,” said Michael Gollner, Associate Professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering at UC Berkeley whose research focuses on fire science. “We’re not worried about the log cabin lighting the forest. We’re worried about the forest lighting the log cabin. Except it’s no longer a log cabin. It’s a whole community.”

Grass fires have long been part of life in Berkeley. On a nearly annual basis before 1923, they burned through the undeveloped North Berkeley hills and ended at the edges of the residential areas, the flames either dying out on their own or put out by residents defending their homes.

“There wasn’t a lot of loss,” said Steven Finacom, a community historian at the Berkeley Architectural Heritage Association (BAHA). He explained that in the 1920s Berkeley residents were very aware of the fire danger. Like today, there were agencies collaborating on fire prevention: The Contra Costa Hills Fire Prevention District included the private water companies and the cities. Fire wardens patrolled the hills to make sure campers weren’t accidentally starting fires with their cigarettes. In August of 1923, there were even talks of building a 60-foot steel watchtower on one of the peaks to serve as a fire lookout.

“They had all the mechanisms in place, but they didn’t have the experience of enormous damage,” Finacom explained. “And then once it came, you couldn’t stop it.”

The fire started just like many others before it—a random spark, perhaps a cigarette dropping or a power line, causing the dry grass to catch fire. But there were a couple major differences: higher density housing and an extremely strong wind. Because of immigration across the bay after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and a surplus of new housing built by architects like Bernard Maybeck and Julia Morgan, residences now filled the hills along narrow, winding streets. Propelled by a hot, dry wind from the northeast (known then as “Santa Ana winds” and now more commonly in the Bay as the “Diablo Wind”), the fire was unstoppable by the time it reached the newly developed areas. Houses exploded in its wake and the blaze was unaffected by the efforts of the Berkeley Fire Department until the wind died down in the afternoon.

“Even if you had 100 fire engines and a limitless water supply, you couldn’t stop it. It stops when the wind dies down. That’s the thing they didn’t quite understand in ‘23,” said Finacom. “And I’m not sure people understand it today.” The fire ended just inches from the north side of Berkeley’s campus on Hearst Avenue, and left over 1,000 students and 100 faculty homeless.

And yet, the scorched neighborhoods in the hills were largely rebuilt in the same pattern as years passed: packed close together along narrow streets. While the first new houses were built of fire-resistant materials such as stucco and tile, wood came back in style in the 40s and 50s, along with the idea of “indoor-outdoor living,” Finacom explained. Even an ordinance against highly flammable wooden roof shingles was repealed after lobbying from the shingles industry. (Next to a photo of a lone, shingle-roofed house standing in a burn area, a pro-shingles pamphlet reprinted by BAHA read, “When its location is considered and how it must have been fairly showered by sparks, shingles certainly did not prove such a fire hazard.”)

Today, little has changed in the residential architecture of the Berkeley Hills. Many of the tightly packed homes still have wood sidings or shingles, and the winding roads make it hard to navigate on a good day. The wildland urban interface—where vegetation butts against homes and communities—has grown, with houses along Wildcat Canyon and Grizzly Peak Boulevard just yards from the fuel-dense Tilden Park. Rather than the danger being constrained to a few months from late summer to early fall, the warming planet means fire season is now nearly year round.

Gollner would like to see all houses today built with fire-resistant roofs—asphalt shingles or tiles with all openings filled in to prevent embers from entering the house—as well as fire proof sidings and defensible space around homes, meaning no overhanging branches or trees or other shrubbery within five feet of the house. All these precautions are outlined in California law, but, in the Berkeley hills, where many houses flout the guidelines, he said, “most of the structures are grandfathered in.”

“Berkeley Hills hasn’t done a lot. They’ve done some things, but there are still winding roads. It’s scary getting in or out of there. There’s tons of fuel. So many wood-sided buildings. It’s better than it was 20 years ago, but it’s not clear how much of a difference,” said Gollner. “I don’t know if I’d live there, you know?”

Gollner said the City of Berkeley has taken some measures, including establishing a Disaster and Fire Safety Commission and an alert system with sirens. On the highest fire hazard days, Berkeley pre-evacuates particularly vulnerable people, such as the elderly, who may have difficulty escaping at-risk areas. A community organization known as the Berkeley FireSafe Council has made it their mission to prevent another Berkeley Fire, and this year they applied for a Chancellor’s Grant from UC Berkeley to collaborate with Gollner’s Fire Research Lab. They focus on fuel reduction, clearing hazardous eucalyptus groves and low branches in the Berkeley and Oakland Hills, and have also helped direct $50,000 of the UC Berkeley-City of Berkeley Settlement Fund towards cleaning up two eucalyptus groves on the university’s property, one below the end of Campus Drive and another under the Vista parking lot, which are part of what they call “The Line of Fire.”

Still, Gollner said, “When you think about it, yeah, gosh, we have wood lined dorms that are right near the front of that 1923 fire.”

Fire mitigation, he emphasized, is both a physical problem and a sociological challenge.

In other words, he wondered, “How do you make people actually change?”

Mostly, Gollner is talking about fire proofing: those shrubs may look pretty hugging your patio, but even just half as many ignitable houses would greatly reduce the burden on first responders during a fire. He also thinks people need to realize how costly the problem is: right now, he says, home insurance in the hills is far cheaper than it should be, given the risk.

Finacom agrees. 25 years ago, when he produced an exhibit on the 75th anniversary of the fire, he had to explain to a lot of people the severity and consequences of having a whole neighborhood catch fire at once. Today, folks are much more aware, but they still struggle to make real changes to their lives.

“I mean, people live in hurricane flood zones and they don’t do anything. And then the hurricane comes,” Finacom said. “I think a lot of people here just sort of hope [that it won’t happen].” But it will.