For Americans, raising children is more expensive, in both money and time, than ever before. Even before the pandemic, when many parents were suddenly forced to become teachers and full-time caregivers, the cost of raising a child can be upwards of $13,000 a year for a middle-income family. And, while it’s too early to predict the long-term affects, one survey from May suggested the pandemic has already impacted the decisions of some 40 percent of cisgender women with regards to having children.

Although the fertility rate has been declining in the U.S., highly educated women are having more children than they used to—while women are, on average, waiting longer to have the first one.

Leslie Root is a postdoctoral scholar in the UC Berkeley Department of Demography, where she received her Ph.D. in August. Her dissertation examined the rise in mean age of childbearing and the increase in fertility in contemporary Russia. She spoke to California about fertility intentions, voluntary childlessness, and the possible effects of the pandemic on these life decisions.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Looking at changing fertility desires among American women, it seems like they aren’t so much opting out as having kids later. Is that correct?

Leslie Root: I think that’s a good summary. But the important thing about fertility is that we never know very much until a given cohort of women is done with childbearing. We’re talking about people who are 45 and older. The last cohort of women that we have data for were born in 1975, so we know women born in 1975 have an average of 2.2 children. When we say women aren’t opting out, that’s who we’re talking about.

I hesitate to use the term “millennial” because it’s not a real demographic term, but I’m a millennial. (I was born in 1984, but someone born in 1996 is also a millennial.) For people my age and younger, we don’t know if they’re opting out, and this is what the big debate is. I think that among people my age, there’s a strong perception that there will be a lot more childless people and that it’s more acceptable to be child-free. And the situation my generation has encountered—graduated from college right before the financial crisis and now facing COVID—means there will be [more] people who will be childless by choice as well. But we don’t know.

What do you think accounts for changing fertility desires and voluntary childlessness?

LR: It’s becoming more acceptable. There are a lot of people who just feel more comfortable saying they don’t want kids now. I think that is something that’s changing in the U.S., although we still have pretty low rates of childlessness, as developed countries go. We have about 10 percent childlessness, which is for the 1974 cohort; they’re 46, and we’re reasonably sure those 10 percent aren’t going to have kids. The Netherlands is like 17 percent, Japan is 28 percent.

That’s a huge gap between 28 percent in Japan and 10 in the U.S. Do we know why that is?

LR: I’m not an expert on Japan, but they’ve had really low fertility for a really long time. It’s very hard in Japan to combine a career and childbearing, because the family is still very gendered. So once you have a kid you’re expected to stay home and just be a mom. I think they have a pretty low rate of marriage as well, because once you get married, you’re supposed to take care of your husband. So women opt out of doing that.

For educated women, I would venture to guess that some of that narrative around what it’s like to be in heterosexual marriage is part of why people aren’t interested in having kids. I think there have been a lot of stories about how men don’t pick up the burden. And I think career women are really aware of that.

What do you think explains the trend among highly educated women in the U.S. who are having more children, later on?

LR: I think there are two components. One is the overall change in childbearing desires in the population at large. The second component is that highly educated women are a bigger share of the population than they used to be. In the 80s and 90s, a lot of women with Ph.D.’s were childless or only had one kid, but they were a really small share of the population. As the population as a whole has gotten more educated, women with postgraduate degrees are more like the rest of the population. And so we have seen in recent decades that highly educated women have more kids than they used to. Part of that is that being highly educated is more common, and part of it is, it’s become easier to be a career woman and also have kids.

What has become easier?

LR: Speaking anecdotally, in academia, it was really uncommon to have kids before you had tenure, even 20 years ago. I felt really lucky in my department—we’re demographers, we study fertility, and my own advisor had both of her kids before she had tenure. So things have become normalized. There’s still a huge gender gap in how parenthood affects people, but in academia, now there are rules about stopping your tenure clock if you’re taking time off for kids. I think that a lot of [women in] higher power jobs have won some concessions in the last few decades. For highly educated women, I think that’s really relevant, this sort of “lean in” era.

In your research you talk about the “popular ethics of childbearing.” What does that mean in modern society?

LR: What I mean by it is that there are moral reasons to have a child, which I think is kind of an old idea. But there are also moral reasons to not have a child, which I think is something much newer. There are outward-facing moral reasons, like environmentalism—people saying, “It’s wrong to have a child because of climate change.” Then there are inward-facing moral reasons: “I don’t want to bring a child into this world that is so messed up or that is going to face civilization collapse.” There are also a lot of personal reasons in that category. For example, “My family has a history of depression. I don’t feel that I would be a good enough parent.”

I think demographically, these moral arguments aren’t that important yet. Most people aren’t thinking about the climate when they’re thinking about the number of children they have. But they’re becoming more important, especially as childbearing becomes more under conscious control—contraception is pretty widespread. In the U.S. we still have a pretty high rate of unintended birth, but it’s going down over time. In an ideal world, every child would be a choice. And when that happens, the moral calculus becomes much more important.

Historically, an expansion of reproductive rights has resulted in decreased childbearing rates. Now, with Amy Coney Barrett’s recent confirmation to the Supreme Court (and the potential for a rollback of reproductive rights), might the 10 percent rate of childlessness drop, if more women lose access to contraceptives or abortions?

LR: I think demographers hesitate to say that restricted reproductive rights will lead to a substantial increase in the birth rate. Broadly it’s true that you can’t create a baby boom by taking people’s rights away. You can create a short-term bump. So for example, Romania had a drastic restriction in the right to an abortion under [former president Nicolae] Ceauseșcu. They had a temporary rise in fertility, but it went back down. At first, people accidentally get pregnant and find they can’t get an abortion, but people change their behaviors and avoid having kids they don’t want.

Now, how could restricted rights affect fertility? You can imagine there will be some people who want abortions and can’t get them. That’s true even today, because so many states have restrictions and people can’t afford to fly two states over. But that could certainly increase. You can also imagine more use of long-acting contraceptives to reduce the unintended birth rate. In that sense, it could work both ways: You see more births, because of less abortion access, and you see fewer births, because women are like, I have to be really careful now.

With regards to the pandemic, do you think parents are going to put off having kids or opt out altogether?

LR: The most conservative answer is, we don’t know yet. People who got pregnant in March will be due in November, December, so we’re going to start seeing what happens. There will undoubtedly be a short-term baby bust. At first people were joking about being at home together, that there’s going to be a baby boom—that was like the first two weeks of lockdown. And then everyone was like, oh, actually, the situation really sucks, and there’s no way anyone’s going to do that. So I think that short term, we’re definitely expecting to see a drop.

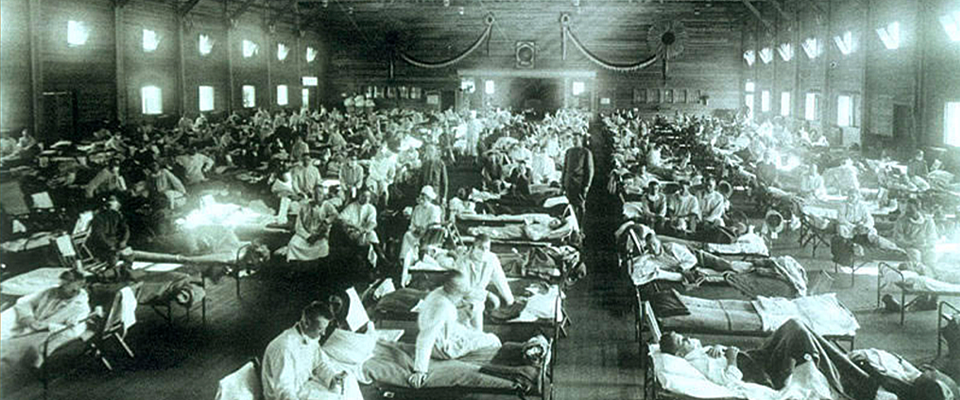

There’s some really clever research just published from demographers in Germany, looking at U.S. Google searches for fertility-related terms, and estimating a 15 percent drop in births over the next few months. I’m a little skeptical of the exact quantitative value of that, but it’s a clever way of looking at it. A 15 percent drop sounds small, but it’s really big. It’s about the same as we saw in the Spanish flu pandemic, and twice as big as we saw in the Great Recession.

I’m curious what people were thinking about in July and August, once they realized we’re not getting out of this anytime soon.

LR: The question is, are people saying, “I was going to have my second kid now, but I’ll have my second kid in two years instead?” Or are people going to give up on that second kid altogether? I actually think there’s reason to suspect that it’ll be a long-term change for a couple of reasons.

First of all, if you’re 22 and something bad happens, and you have to put off your second birth, it’s no big deal. But as the mean age of childbearing rises, it starts to matter a lot. If you’re 40 and planning to have your second kid, there’s a time clock on that. Also, a lot of people are in situations where they need assistance to have a kid. You might be in a queer couple and need an egg donor or you might be older or a single mom by choice and need IVF. That adds another component of access to medical care because a lot of fertility clinics stopped working for months.

But there are also the economic effects. The pandemic has been a lot worse, in terms of employment, for women, especially in service industries. They’re leaving work and not getting it back for a long time, and there’s been no support from the government. That has long-term effects. American fertility dropped during the Great Recession [of 2008], and for younger Americans, it never really recovered with the economic recovery.

The third aspect is the burdens placed on parents. The idea is that as the norms of child quality [the amount of time and money invested in each child] go up, the number of kids you have goes down. It becomes more expensive in time or money to have a kid. That’s just a feature of modernity—that now we send our kids to school, and we expect that we’ll pay for college. And maybe we have extracurricular activities and all this stuff that takes time and money. I see the pandemic as having changed how expensive it is, especially in time, to have a kid, particularly for parents of school-aged children. These parents who are working and trying to manage one or two or three kids—I would imagine that experience is going to stick with them for a long time. I’m watching that, thinking, “do I want to have another kid if I know there’s a possibility that I might be completely in charge of their education?”

I think there are a lot of open questions about if we’re going to be traumatized by the pandemic for our whole life. Maybe in 10 years, we’ll find our old masks in a drawer and laugh. But maybe it sort of breaks your trust in society. People can often be flippant and say, “If you don’t want to raise them, don’t have kids.” But the reality is that humans are social creatures, and we don’t parent in isolation. Human babies and children require so much time and energy, that our species evolved to have what we call “alloparenting,” assistance from the community and grandparents and aunts and uncles. The more burden we’re placing on individual parents…who thinks that’s worth it?

Finally, there have been some tensions between parents and child-free people. In addition to a Twitter war about “who has it worse,” there was an article in the New York Times about how childfree tech workers were begrudging their employers giving parents more paid time off because of the pandemic.

LR: I think it’s an ongoing war. The pandemic has made it worse, but this is a recurring theme. Some say, “American society is too child-friendly. Why are you bringing your kid to the bar?” Others say, “How come every time I go out with my baby, I can’t find a bathroom with a changing table?” There’s no political and social agreement that having children is important. There’s no social contract that “we need kids in order for society to continue, and therefore, parenting is a very important role in society, and parents should be given, X, Y, and Z accommodation.” There are a lot of Americans who would not agree with that.

These conflicting trends pit parents against non-parents. I don’t know how we resolve that, but I do see it as a really big problem that partly stems from the fact that we give so little to parents. Maybe if there were nationally mandated childcare leave and preschool for all, those material investments would actually become psychological investments. I like to believe that, but I just see a narrative of childbearing as becoming more and more about personal choice, that if you have kids, it’s on you to raise them.