It now appears that some primates other than Homo sapiens were truly sapient.

That, at least, is the takeaway from a paper published in the journal PLos One, which determined that spear tips or arrowheads recovered at a mid-Pleistocene era obsidian quarry in Ethiopia were hewn by representatives of Homo heidelbergensis, a hominid that hunted and gathered in Africa, western Asia and Europe 600,000 years ago.

The 280,000-year-old points predate the earliest known fossils of Homo sapiens by at least 85,000 years—and in the process sink the notion that our species has been the only one to evince true powers of reasoning since life first kindled in the primordial broth.

“These points were used either as throwing spear or arrow points,” says the lead author of the paper, UC Berkeley Human Evolution Research Center postdoctoral fellow Yonatan Sahle, who is returning to the international team’s dig in Ethiopia this week. “We can tell that because microscopic examination revealed micro-fractures that can only be caused by (high velocity) impacts unrelated to the knapping (shaping) of the points or thrusting.”

The discovery has deep implications for both paleontology and philosophy. On the scale of evolutionary development, the ability to make true throwing spears may be on a par with mastering language, Sahle says. And that begs the question: Do you have to be human to be, well, human? Maybe not.

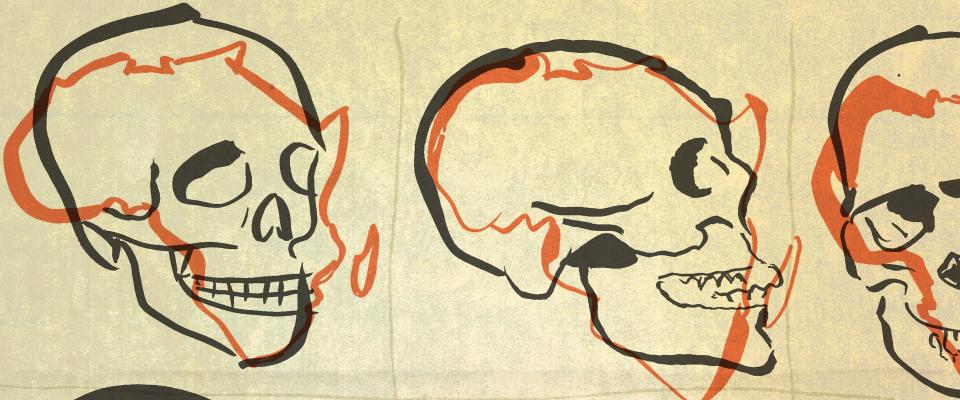

Members of Homo heidelbergensis were certainly robust hominids who possessed many characteristics of Homo sapiens, though they more closely resembled Neanderthals. However, they were not—to borrow a line from the great Tod Browning movie Freaks—One of Us. And yet, they apparently manifested the higher analytical processes that we so blithely invoke to separate ourselves from our “primitive” antecedents.

Chimpanzees have been observed throwing stones, and baboons are known to use sticks as clubs. But Sahle observes that fabricating and utilizing a throwing spear is exponentially more advanced than these activities.

“It’s not just a matter of knapping an obsidian point, though that in itself is a sophisticated process,” Sahle explains. “You also have to know how to select and shape a shaft, and how to bind the point to the shaft with either some kind of natural mastic or with plant fibers or sinew. And you have to know how to throw it. We know that Neanderthals couldn’t or wouldn’t throw spears. They only used thrusting spears. So it’s significant that Homo heidelbergensis—who antedated Neanderthals—had mastered these skills.”

The excavation where the points were found, an obsidian-rich site known as Gademotta, is looming increasing large in hominid history. Experts believe it’s highly likely that this is where the whole process of higher thinking began.

“The earliest Homo sapiens fossils were found both north and south of Gademotta” at a distance of 2.5 kilometers each way, says Sahle. “Points from a wide area have been sourced to this particular quarry. To mid-Pleistocene hominids, this was a very special and important place. I think it’s probable that this is where and when sophisticated tool making began. You’d need a combination of very rare factors all coming together to push it back any farther. I don’t see that happening.”