Americans have been arguing about taxes for decades. In recent months, soaking the rich with higher taxes has become a battle cry for progressives. Left-leaning politicians argue that higher taxes on the wealthy would reduce inequality and raise substantial revenue without damaging the economy.

The latest debate started with a proposal from a rookie, the newly elected Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who wants to raise income taxes to 70 percent on the richest Americans. Quickly upping the ante, Senator and presidential hopeful Sen. Elizabeth Warren proposed a tax on assets—not just income—of the very wealthy above $50 million.

Left-leaning politicians argue that higher taxes on the wealthy would reduce inequality and raise substantial revenue without damaging the economy.

While some critics are rolling their eyes, there is substantial evidence that the U.S. did enjoy robust economic growth during historical periods when income tax rates were substantially higher than they are now. And according to UC Berkeley economists, a rate even higher than that proposed by the New York Democrat would be broadly beneficial.

“The optimal top tax rate could be over 80% and no one but the mega-rich would lose out,” says Emmanuel Saez, Berkeley professor of economics and director of the Center for Equitable Growth. “Lower paid workers and consumers will get a bigger share of the economic pie.”

In light of the ongoing dispute, we took a close look at Ocasio-Cortez’s proposal and measured it against research by Cal experts. Here’s what we found:

Ocasio-Cortez’s tax plan has been mischaracterized.

The 70% tax rate would only affect a fraction of wealthy Americans—and only a fraction of their income.

The marginal tax rate is only imposed on the last dollars of earned income. So, in today’s system, a person earning $220,000 a year after deductions will only pay the top tier 37 percent tax on income above $200,000. All income below that amount would be taxed at a lower rate.

And under Ocasio-Cortez’s plan, no one earning less than $10 million would be hit with the 70 percent tax rate.

Higher taxes on the rich were once the norm.

You might have heard the argument that, for much of the 20th century, income taxes were considerably higher for the wealthiest Americans. And despite some grumblings from conservative critics, that’s essentially true.

To put the Congresswoman’s proposal in perspective, until the Reagan era, marginal tax rates (that is the tax rate affecting the highest earnings of the wealthiest taxpayers) were as high as 91 percent. Rates were at that seemingly stratospheric level from just after World War II until 1974. They then dropped to 70 percent and stayed there until the mid-80s when President Regan cut them from 50 to 37 percent. Rates subsequently crept up a bit but were lowered to 37 percent by President Trump’s 2018 tax cut.

Infographic by Leah Worthington // Source: Tax Foundation Chart of Federal Tax Rates

Marginal rates were also triggered at a lower earnings level in the past. During the Eisenhower administration, the top rate (91 percent) for a single taxpayer kicked in at $200,000, the equivalent of about $6.7 million today, figuring in inflation and economic growth, Saez says. Though relatively few people surpassed that income level at the time, it’s still much lower than the $10 million threshold proposed by Ocasio-Cortez.

Higher taxes on the rich reduce income inequality.

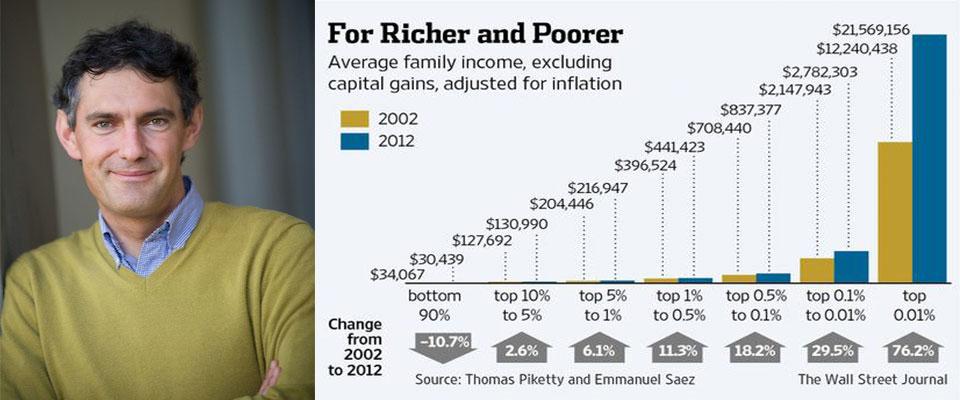

While taxes on the rich have declined sharply, inequality has grown by bounds, with the wealthiest Americans taking in an increasingly sizable share of the country’s total income. The top one percent of income earners—those with annual income above about $400,000—has increased dramatically: from 9 percent in 1970 to 23.5 percent in 2007. That’s the highest level in nearly a century and much higher than in European countries or Japan, according to Saez and former Berkeley economist, Peter Diamond. And by all accounts, the so-called one percent have garnered an even larger share of the country’s wealth since the end of the 2008 recession.

Even if marginal tax rates increased by much less than Ocasio-Cortez has proposed, the impact on revenue would be massive. Increasing the top rate to 43.5 percent would be sufficient to raise revenue by 3 percent of GDP, or hundreds of billions of dollars a year, according to Saez and Peter Diamond, former Berkeley and current MIT professor of economics.

That change would do more than swell government coffers. It would shift some of the tax burden from the middle and working classes to the wealthy, thus narrowing the wealth gap.

Higher taxes on the rich don’t slow the economy.

Putting aside questions of fairness, conservatives claim that cutting taxes on wealthy business owners will boost economic growth and end up benefiting workers lower on the income ladder. But Berkeley economics professor Gabriel Zucman, in an earlier article co-written with Saez, dismisses that argument:

“The idea is that if the government taxes the rich less, the wealthy will save more, grow U.S. capital stock and investment, and make workers more productive. The evolution of growth and inequality over the past three decades makes such a claim ludicrous.”

Infographic by Leah Worthington // Source: Tax Foundation Chart of Income Taxes Today vs 2017

But how do we know that tax hikes on the wealthy won’t dampen the economy? To answer that question, Berkeley professors Christina and David Romer examined tax policy and economic growth between the World Wars, a period of notably consistent tax rates.

The Romers found that higher marginal rates had no significant effect on productivity and that interest rates on bonds, a key economic indicator, were largely unaffected. Nor was there a significant slowing of capital investment in machinery, construction, or the labor force.

Furthermore, they found that taxable income was only a relatively small part of the overall income enjoyed by the wealthy: Capital gains, stocks, real estate, and other financial mechanism are not directly affected by the income tax and remain available for investment.

Finally, there’s this common-sense insight noted by, among others, Nobel Prize winner and New York Times opinion columnist Paul Krugman: Earning an extra $2000, while inconsequential to the rich, means quite a lot to someone whose income is just $20,000. Economists call this diminishing marginal utility, and, as Krugman explains in his op-ed, it suggests that “we shouldn’t care what a policy does to the incomes of the very rich. A policy that makes the rich a bit poorer will affect only a handful of people, and will barely affect their life satisfaction.”

Conservatives say she’s wrong.

Much of the criticism directed against Ocasio-Cortez’s tax plan was nakedly partisan. But there are serious economic arguments against it as well.

- Tom Church, a research fellow at the Hoover Institution, says that Saez’s analysis leaves out a crucial element: the overall tax burden imposed on the wealthy. “One thing to make clear is the enormous difference between marginal tax rate and effective tax rate,” he wrote. The effective tax rate is the actual tax a person pays after deductions and other factors are taken into account and is typically much lower.

- Scott Greenberg, a senior analyst with the conservative Tax Foundation, argues that the 91 percent marginal tax rate in the 1950s “likely led to significant tax avoidance and lower reported income.” Greenberg also notes that the number of people directly affected by the top rate in that period was very small, only about 200,000 households.

- Stanford University economist Charles Jones argues that “new ideas drive economic growth, and the reward for creating a successful innovation is a top income.” High tax rates, he says, discourage the creation of productive new ideas. He suggests that to encourage more investments in the economy, the rich should be taxed at “a negative rate.” In effect, they should be subsidized.

What to expect going forward

For now, the arguments are largely academic. It takes a vote by both houses of Congress to approve a significant change in the tax code and then it must be signed by the president. The chances of that happening in the next two years are essentially zero.

Even if the Democrats capture both houses of Congress and the presidency, reversing the Trump tax cuts is hardly a slam dunk.

But the debate is worth having since tax policy will be on the agenda as the 2020 elections approach, says Robert Van Houweling, professor of political science at Berkeley. Historically, the public has favored higher taxes on the wealthy, and discussing the various plans now being floated is a way to test out new ideas for effectiveness and public approval, he says.

Interestingly, the seemingly more radical proposal by Senator Warren, which Saez and Zucman have been advising her on, polls better than Ocasio-Cortez’s, although both have significant support. Because most people probably don’t understand that the 70 percent tax rate only applies to the portion of incomes above $10 million, Ocasio-Cortez’s plan strikes them as unfairly high, explains Van Houweling. But Warren’s plan, which would actually cost the super-rich much more money, sounds relatively modest because it involves a maximum bite of 3 percent.

Even if the Democrats capture both houses of Congress and the presidency, reversing the Trump tax cuts is hardly a slam dunk. “It’s always easier to cut taxes than it is to raises taxes,” says Eric Schickler, a professor of political science at Cal.

How progressives could win the tax fight

Schickler has a strategy tip for those who want to raise taxes: Make it clear that the middle class is getting a direct benefit from a change in the tax law. Progressive politicians could pair an increase in taxes on the high end with a tax cut for lower earners. Or they could take a page from the Obama playbook: The former president used a tax increase on higher earners to partially fund Obamacare.

Saez and Zucman go further, arguing in a recent column that raising revenue isn’t the real point of higher tax rates: “The point of high top marginal income tax rates is to constrain the immoderate, and especially unmerited, accumulation of riches. From the 1930s to the 1980s, the United States came as close as any democratic country ever did to imposing a legal maximum income. The inequality of pretax income shrank dramatically.”

In other words, tax policy goes to the heart of our ideas about economic fairness, social justice, and the optimal way to raise revenue to fund the government. It affects everyone’s wallet, the services the government can afford to provide, and perhaps most significantly, the degree of financial inequality we as a society are willing to tolerate.