What to fix, and what to replace? That’s the big question for Orville Dam. It has been almost a year since water brimmed to the top of Oroville reservoir and the tallest dam in the United States suddenly showed signs of possible, even imminent failure. Emergency releases eroded both the primary and secondary spillways with horrifying rapidity, and evacuations were ordered for 200 thousand downstream residents.

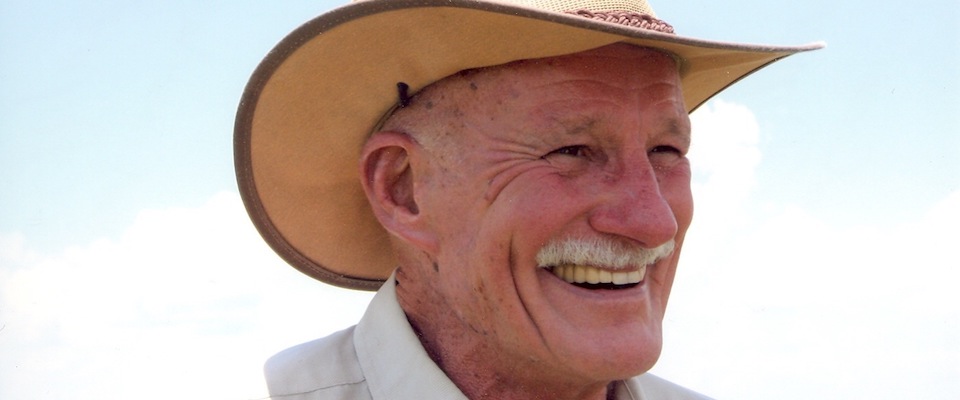

Catastrophe ultimately was averted, and crews have since worked furiously to repair the damage. But the problem is unlikely to be remedied by any patch job, warns UC Berkeley professor emeritus of engineering and renowned forensic engineer Robert Bea. Oroville’s problems are so deep and structural that “fixing” it is not realistic. That’s especially the case at the “headworks” for the primary spillway, the structure that controls releases from the reservoir.

“DWR [the State Department of Water Resources] is currently replacing [the eroded] primary spillway, but has tried to ignore the headworks,” Bea says. “They recently realized they only have one power supply to open and close the gates. They need to have an emergency power supply installed.”

The dam is emblematic of a larger institutional dilemma: a basic misunderstanding of the word “safe.”

Indeed, says Bea, “the jury is still out” on the dam itself, the massive plug of earthen fill that backs up the Feather River. There is leakage at some places on the dam’s face, suggesting that the structure itself may be unsound.

“Maybe the dam needs rebuilding, maybe not,” says Bea. “We simply don’t know, but we need to know. FERC [the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission] thinks there should be additional instrumentation on the dam to survey the situation, and I agree. But DWR hasn’t supported that option.”

To Bea, the dam is emblematic of a larger institutional dilemma, one he has pounded on for decades: a basic misunderstanding of the word “safe.” A founder of UC Berkeley’s Center for Catastrophic Risk Management, Bea says many large American infrastructure projects are inadequately designed for safety, the result of a skewed engineering ethos and government agencies that are ignorant of the problem.

Bea and his colleague Tony Johnson produced a report on the root causes of Oroville’s spillway failures five months after the incident. Earlier this month, an independent team of forensic investigators released their own analysis.

Their report is unsparing in its criticism of the design and construction of the dam and DWR’s culture. It noted that the dam had poor foundation conditions that were noted in multiple geology reports, but that these deficiencies were “…not properly addressed in the original design and construction, and all subsequent reviews mischaracterized the foundation as good quality rock. As a result, the significant erosion of the service spillway foundation was also not anticipated.”

The report added that DWR’s commitment to dam safety, “…although maturing rapidly and on the right path, was still relatively immature at the time of the incident… .” The report further characterized the agency as “somewhat overconfident and complacent…and insular, which inhibited accessing industry knowledge and developing needed technical expertise.”

Bea is even more pointed in his criticism of DWR, maintaining that it’s not just a matter of what the agency ignored or scamped during the decades since Oroville was built. He’s worried about what the agency is doing—and not doing—now. Specifically, he cites testimony given by DWR staffers at a January 10 hearing of the California State Assembly standing committees on water, parks, and wildlife.

“They asked [DWR deputy director] Cindy Messer if DWR agreed with the forensic team’s report, and it was really interesting to watch her facial expressions,” says Bea. “She said she didn’t agree with all of them. Then she [and deputy director Joel Ledesma] were asked how long it will take DWR to implement the recommendations, and they said four to six months. But there’s no way in hell they can do that. It’s clear to me that the leadership at DWR still doesn’t get it. They’re ignorant, not evil, but it’s unfortunate that they get very, very defensive under intense scrutiny.”

During the hearing, Messer maintained that DWR had repaired the main spillway, “bringing it to today’s standard…” But that’s not true, says Bea, especially if “today’s standard” reflects any real commitment to public safety.

“They’ve poured 500 million dollars into the two main sections of that spillway,” says Bea. “They had to excavate 100 feet of rotten rock and then refill it with compacted concrete. Well, not long ago the media reported that there were alarming new cracks in the concrete. And it was only then that DWR addressed the issue, maintaining such cracks are to be expected. I was queried about this, and I said cracks in concrete should never be expected or tolerated in important structures. Would we tolerate them in nuclear power plants? But DWR insists they’re small, they’re not critical. And in my mind, that puts us right back on the road that led to February 7, 2017.”

“Oroville is closer to the standard than an anomaly based on inspection reports I’ve received on [California] dams.”

Bea has a long history of working on offshore oil production projects, and he says that oil companies tend to respond with alacrity to safety concerns, especially when they make a big splash in the media. There is a simple reason for that, he observes: safety mishaps cause intensely negative PR and production breakdowns which, in turn, reduce company revenues and dividends, ultimately enraging shareholders.

“Company executives don’t want to confront angry shareholders, so they typically deal with safety problems quickly and proactively,” Bea says. “They learn what ‘safe’ really means from experience, and if they ignore those lessons, their shareholders will remind them. The problem is that DWR doesn’t have any shareholders. So they haven’t been forced to learn what ‘safe’ means for Oroville.”

And it’s not just Oroville, says Bea. California’s water storage and delivery system as a whole is in a sorry state. And that isn’t just his opinion.

“Oroville is closer to the standard than an anomaly, based on inspection reports I’ve received on [California] dams,” Bea says. “The American Society of Civil Engineers has been worried about California’s dams for years. They released an annual report card on national infrastructure, and their 2017 grade for state dams was D-.”

The reasons for such an abysmal evaluation are predictable, says Bea: the system is more than 50 years old, it was designed imperfectly, and these shortcomings were never remedied. That means there is no easy fix. It doesn’t do any good to just throw money at the problem. That was done following Hurricane Katrina, says Bea, when more than $100 billion poured into New Orleans but little if anything was accomplished to protect the city from similar storms. To effectively address the risks beleaguering California’s dams, Bea insists, we have to abandon the “paste and patch” approach and start from the beginning.

“That means we have to do quantitative assessments for each of these dams,” Bea says. “That’s quantitative in terms of both cost and safety. How much money will it cost to get a degree of safety that is precisely defined, that meets a specific and rigorous standard? It’s obvious DWR doesn’t know how to fix Oroville. [Portions or all of it] could be rebuilt completely so that it does meet a necessary safety standard once one it is defined. And it’s also clear that it won’t be cheap. But even a complete fix of Oroville would cost less than a complete failure of Oroville.”

Calls to DWR Director Grant Davis for response to Bea’s comments were not returned.