Welcome to the California Time Capsule, where we republish articles from the magazine’s more than 125 year old archive. Feeling nostalgic for the early days of Rock n’ Roll and legendary venues like the Cow Palace, Winterland, and the Avalon Ballroom? This 1967 Q&A featured music industry royalty with promoter Bill Graham; Phil Spector, the Beatles producer (who was later convicted of murder); Ralph Gleason, the co-founder of Rolling Stone; and more. While the dollar amounts they discuss may seem like chump change today, the “the generation gap” they described is still with us.

In two University Extension conferences a fresh light was thrown on rock ‘n’ roll music and the gap between generations. The first conference brought together in lectures and panel discussions academic people, a critic, musicians and others intimately connected with the rock ‘n’ roll industry. The second, with experts from the social sciences and related disciplines, probed the generation gap–the lack of understanding and communication between generations, a situation common through history, but more noticeable today. Extension’s Liberal Arts Department put together the programs from which CALIFORNIA MONTHLY has drawn material for this special issue.

Peter Sellers, in an early-’60s record, satirized the rock ‘n’ roll scene as it was then by singing in the character of a rock star lamenting the sudden decline in his popularity (“me discs are slipping”) because he was getting old: nearly nine.

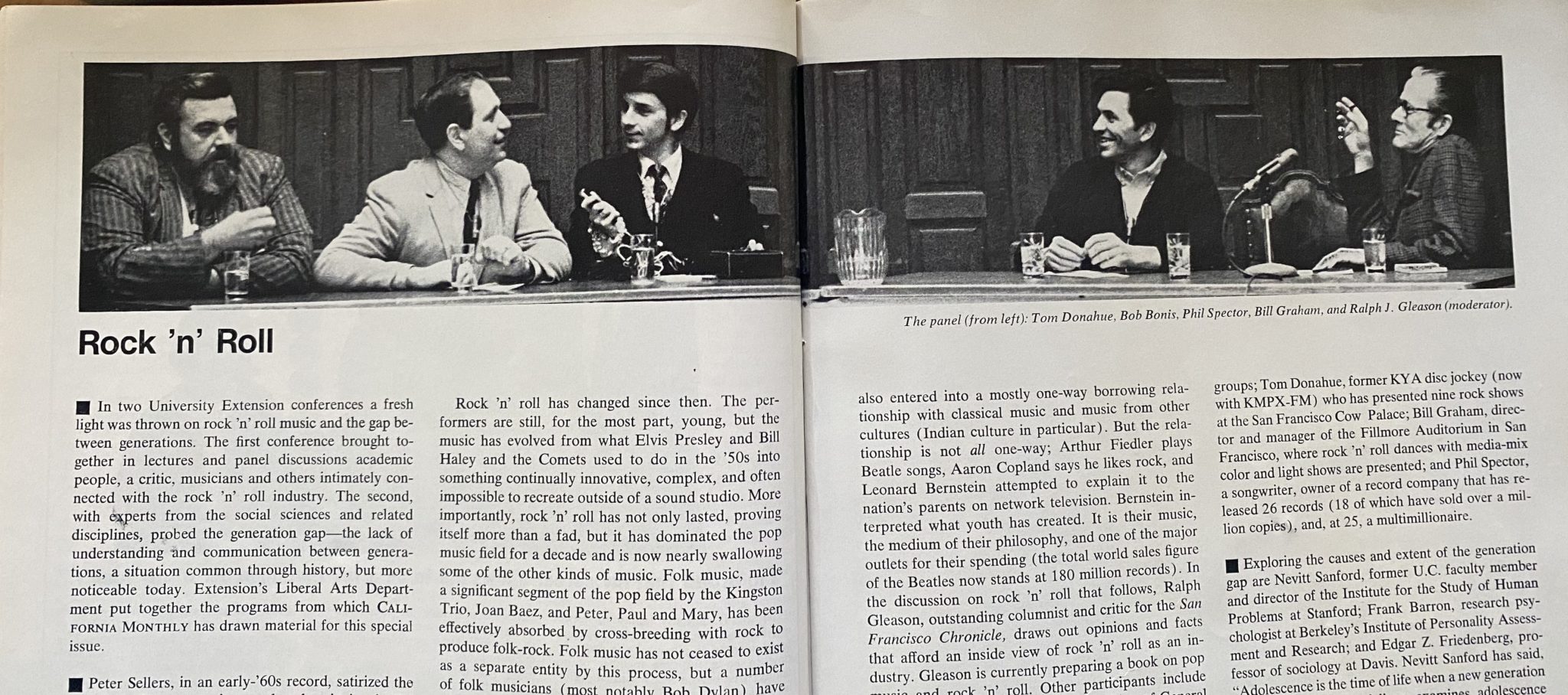

Rock ‘n’ roll has changed since then. The performers are still, for the most part, young, but the music has evolved from what Elvis Presley and Bill Haley and the Comets used to do in the ‘50s into something continually innovative, complex, and often impossible to recreate outside of a sound studio. More importantly, rock ‘n’ roll has not only lasted, proving itself more than a fad, but it has dominated the pop music field for a decade and is now nearly swallowing some of the other kinds of music. Folk music, made a significant segment of the pop field by the Kingston Trio, Joan Baez, and Peter, Paul and Mary, has been effectively absorbed by cross-breeding with rock to produce folk-rock. Folk music has not ceased to exist as a separate entity by this process, but a number of folk musicians (most notably Bob Dylan) have entered into a kind of musical Alliance for Progress with rock in which rock is coming out ahead. Similar alliances have been made with country and western music, rhythm and blues music, and jazz. Rock has also entered into a mostly one-way borrowing relationship with classical music and music from other cultures (Indian culture in particular). But the relationship is not all one-way; Arthur Fiedler plays Beatle songs, Aaron Copland says he likes rock, and Leonard Bernstein attempted to explain it to the nation’s parents on network television. Bernstein interpreted what youth has created. It is their music, the medium of their philosophy, and one of the major outlets for their spending (the total world sales figure of the Beatles now stands at 180 million records). In the discussion on rock ‘n’ roll that follows, Ralph Gleason, outstanding columnist and critic for the San Francisco Chronicle, draws out opinions and facts that afford an inside view of rock ‘n’ roll as an industry. Gleason is currently preparing a book on pop music and rock ‘n’ roll. Other participants include Robert Bonis, head of the Youth Division of General Artists Corporation, which handles The Lovin’ Spoonful, The Mamas and The Papas, The Cyrcle, and other groups; Tom Donahue, former KYA disc jockey (now with KMPX-FM) who has presented nine rock shows at the San Francisco Cow Palace; Bill Graham, director and manager of the Fillmore Auditorium in San Francisco, where rock ‘n’ roll dances with media-mix color and light shows are presented; and Phil Spector, a songwriter, owner of a record company that has released 26 records (18 of which have sold over a million copies), and, at 25, a multimillionaire.

Gleason: Rock ‘n’ roll is big business, if anything that we know about it can be believed, but sometimes we fail to realize just exactly how big that big business is. I thought we might open this by asking just how big a business is rock ‘n’ roll?

Bonis: It’s a huge business. Enough to have several agencies do nothing but book rock ‘n’ roll performers and make it a multi-billion dollar business overall.

Gleason: On a tour with the Beatles or Rolling Stones, after a month or 20 concerts, what kind of a total gross is involved?

Bonis: The Beatles gross last summer, for example–14 cities, 14 concerts–was well over a million for their share of the percentages. Well over a million dollars. That’s just their share of all the concerts.

Donahue: I paid them 94 thousand for the performance at Candlestick.

Bonis: And in Shea Stadium for example, their share was well over 200 thousand.

Gleason: But they furnish the whole show, right?

Bonis: Yes, they bring the whole show. But you hire an airplane to transport the whole show-about 65 to 70 people going from town to town. There are an awful lot of costs to the promoter. The cost of the airplane, the cost of the acts. The promoter’s cost as such was more in San Francisco than it was in any other city because the stadium charged more.

Bonis: So in other words, he’s doing it as a charitable institution here in San Francisco.

Donahue: For the kids.

Gleason: You lost money with the Beatles in San Francisco?

Donahue: No, we made a little money. We made very little, actually, because the Beatles got 65 per cent, the city got 15 per cent. That’s 80 per cent. On top of that, you’ve got the basic promotional cost, plus the city gave us Candlestick Park, but that was it. We had to provide everything else–all the rent-a-cops, as you call them, the unbelievable number of little costs that were inserted, running power lines to second base for $3,500 the day before the show, $800 to take the trash away. It was ridiculous. But the city made their piece of money and they were happy, and the Beatles got a lot of bread. My kids got to meet the Beatles-that’s what I got out of it.

Gleason: Is it different in San Francisco than in other cities, Bob?

Bonis: Well, San Francisco got more money than the other cities usually got. For example, in St. Louis there’s a brand new park. They have so-called port- able stands. The stands themselves for baseball are on the third base and the first base line, but for football they come out on tracks and they seat 5,000. The rest of the stands are stable and so they set up the field as a football field for the Beatles concert because they said that’s the way it must be and then charged $500 at the last minute–to the promoter–to move them out on the tracks. And then after it was all over they said there’s a baseball game the next day and you’ve got to pay another $400 to move them back. The cities themselves made the most money of all.

Donahue: Yeah, they cleaned up.

Bonis: Well, on the tour there were a lot of so-called hidden costs, but I’ve been around quite a bit on these tours with the Stones and the Beatles, as you know, and this last trip revealed costs that I didn’t even know about.

Donahue: I don’t think there is as much big money for the groups in touring today as people think there is, because of the cost of touring. If you get a gig in San Antonio for $2,500, it may sound like a lot of money for a half an hour, but by the time you put five or six musicians, two or three people traveling with them, the instruments, everything, aboard the plane, you’re halfway to San Antonio and you’re already losing $20. There are some groups that will definitely make money consistently. The Beatles, the Stones, The Mamas and The Papas, the Beach Boys, and the Lovin’ Spoonful.

Bonis: Well, I have one that I think is the best of all for expenses–Simon and Garfunkel. There’s just the two of them and no electric instruments. Just acoustic guitars. No overweight problems with their baggage and they take their road manager to collect the money while they’re singing and that’s it. That’s just airplane transportation for three people. They do the whole concert by themselves.

Donahue: Then I ought to get a better rate on them.

Bonis: Sorry about that.

Gleason: Where does the money come from? If there’s no money in touring, how does the artist make money–if indeed he does?

Donahue: I don’t think there is that much money in it today for acts. I don’t think there’s nearly as much money being made by hit record stars–if you want to call them that–as people think there is. It depends upon how the act is used. I mean a good example of proper handling of an act is the Beach Boys, except they didn’t even go on the road until they had four or five number one records, so when they did, they made big money wherever they went. They ran an intelligent tour and they hadn’t been overexposed in those Dick Clark tours that drag around the country interminably. Or overexposed anywhere except in California, where they had made every bar mitzvah and gas station opening for a couple of years.

Gleason: Okay, so an act has a hit record, how much money can it make out of that record?

Spector: The Righteous Brothers got royalty payments on four records of over $300,000.

Bonis: You’re not going to make it until, as Tom said, until you make a few hits. You’re not going to make much money from the touring aspect, simply because you can’t just pick up the phone and call logical cities enroute, because there aren’t enough records sold in the beginning to have everybody take the act. What we’re talking about is the need for the records and the tours combined. But in the beginning it’s the records that are making the money- on the first couple of hits-because you’re not going to make much money touring. Until you have enough records to draw an audience and to get a respectable amount of money and you don’t have to hop from here to kingdom come to get from place to place. Which is what you have to do in the beginning. It practically eats up all of your costs you know, transportation and everything else.

Donahue: You’ve got to have a couple of records before you can do anything.

Bonis: Or you can go with a Dick Clark package or something that has ten acts, each with one hit.

Gleason: What do you mean by Dick Clark package? What’s a Dick Clark package?

Donahue: I’m involved in a music newsletter called Tempo and they were doing “Ins and Outs of the Business” one time, and they said Dick Clark tours are “out” because it’s uncool to be that ostentatious about the fact that you’re no longer making it. Dick Clark tours primarily are like Bryan Hyland–acts that maybe had hit records three or four years ago- and one or two current acts. He had the Supremes when they were at their hottest. He bought them early and very cheap. And he’ll put together–yeah, he got the Monkees–and he’ll put together a package of 10 or 12 acts and have sometimes three tours on the road at a time, but they specialize in hitting towns like Dayton and Hartford. They get into those half million places where they’ve never seen anybody and you don’t know- even Bryan Hyland can be very big.

Gleason: How much control does the artist have over what he does on a show like that?

Bonis: It depends on how good his agent is, actually. In other words, really, that has to be discussed before the artist is sold–what billing, where on the program, how much time.

Gleason: When he has the time he can do whatever he wants to, is that it?

Bonis: On the Clark package, pretty much, on some other packages, no.

Donahue: I think it’s changed in this sense. When we first started having shows at the Cow Palace, just six years ago, you would have 24 acts and nobody had instruments. They were all single acts and had a 30-piece band. The act would come in and half the time the only songs they knew were maybe one side of their record, maybe two if they were lucky. Everybody wanted to do What’d I Say. It was a bollix. But now it’s totally a different scene, in that the groups are self-contained entertainment units to a much greater degree. They are capable of playing their songs; they are much better musicians, and they’re capable of being performers. With the other groups, you used to have to do 12 and 14-hour rehearsals.

Gleason: Is this thing changing, the way tours are going out, the way artists are being presented? Bill, do you find a difference in this?

Graham: I’m on a different level, local level. We can’t afford to bring the big groups in. I know that they do come in. The Mamas and Papas don’t go out too often, but when they do they hit very well and very carefully. They hit San Francisco a couple of months ago and sold out the Civic Auditorium and smelled fair weather and came right back and went over to Berkeley a couple of weeks later. So they do go out and where the grass is green they come back.

Spector: If you’re selling a lot of records, you don’t really have to work very much. You really don’t because you’re making so much money. You can make a lot of money on royalties, especially you know, like the Mamas and Papas and Dylan. I mean they have relatively small recording costs and usually it’s absorbed by the company if they have good contracts, so all of it is profit.

Donahue: Actually, a successful act today who write their own material can make most of their money from publishing and writing. That’s where the bulk of their money is going to come from. That’s where the money’s always been in the record business anyway.

Spector: Why the Beatles stayed on the road as long as they did is beyond me. They didn’t have to go. I mean it’s a pain in the neck to travel like that, and live in armored cars, kids running all over you and stepping on you-

Bonis: The Beatles’ feeling, I know, is that they owe it to the fans. To come out and tour–for example, in England–you can’t conceive of how it’s done there. In England, there are no places as big as the ones you have here. In England, the Beatles, Stones and all the other top English acts have to play in theaters maybe twice the size of this one [Mills College Concert Hall, capacity approximately 500] and do two shows. And If they go in and rent the theater for a very small amount of money and sell out the house-first of all you can’t scale the house-_you can’t charge as much. In England, if you charge more than $1.80, $2.00 for a ticket, no one is going to show up for it because they can’t afford to pay more. So when we’re talking about the Beatles taking home 200-and-some-odd-thousand from Shea Stadium-the Beatles played a show a year and a half ago, they played a mime show, which is an English tradition, at a theater in London, the biggest one there, for two weeks, seven shows a week, two shows on one of the days and one day off, and they didn’t clear.

Graham: Probably one of the great tragedies here in the states is that you’ve got 50,000 screaming maniacs sitting in the stands mouthing the words to songs that they know by heart and if that’s entertainment, then eventually I’m going to get out of it. It’s a shame that the Beatles, or Dylan, or Donovan can’t come over here and you can’t put them in a house for four or five thousand people where they can hear them and dance and do what they want. If the Beatles are around long enough, within another couple of years, I think it would be nice to be able to offer them anything they want, at a loss, but let them do it the right way. Let them come into a place of 5,000 people and let them get paid 50 thousand–I don’t think it makes any difference, but let people do to them what should be done, sit, move, or dance and talk.

Spector: Yes, but that’s risky, you know.

Graham: No, it isn’t. Not here.

Spector: You know, somebody shot the President in this country. They’re a little startled about that kind of stuff.

Graham: That was not in this country–that was in Texas.

Bonis: Again, Phil brings up a problem. There were all kinds of threats on the last Beatles tour. In Memphis, we had to build special barriers and hire a hundred extra plainclothesmen. Someone threw a firecracker and scared the policemen half to death. You just can’t tour the Beatles any more because their musical concept is such that you need more than a 30-piece orchestra to take care of their musical needs, you know, so that’s one of the reasons and probably the main reason they’ve stopped touring. You know from their latest records you need flutes, cellos, and that’s exactly why they stopped touring, even though they were always limited.

Donahue: That’s getting back to the old thing of trying to reproduce the record. There are very few acts that have successfully reproduced their records on stage. Half of the time it’s because when the record was cut Hal Blaine was on drums instead of the drummer that they got in the group; somebody else was playing bass; maybe two guys in the group weren’teven in the studio for the session and heard the record for the first time on the LP. I mean that is just part of the business that does exist and that’s why most of them can’t recreate.

Bonis: Yeah, well Phil’s records are the toughest. His records are sound more than music, whereas the Lovin’ Spoonful type of group play their own instruments on the sessions and everything else and make it a little easier. They make it easier on themselves. On some, like Phil’s Righteous Brothers records, the Lord knows what you need to reproduce that kind of sound.

Spector: The Lord does know. You know, I went to the Beatles’ concert once–I couldn’t hear anything. I couldn’t hear anything at all. I didn’t know what they were singing, all I heard is “Do you…” that’s what I heard–and a lot of screaming, and then “I wanta…” That’s all I heard. I didn’t think they were singing at times, you know. They were scared.

Donahue: The Beatle concerts from a musical point of view don’t exist. They’re another kind of happening. You can dig all those people flipping out. I know I liked the one I saw in L.A. in the Hollywood Bowl because when they came on, all of the sudden, a couple hundred thousand little girls pulled out Brownie cameras and everybody hit the flashbulb at the same time.

Spector: Did you ever get hit with a jelly bean from about 300 feet–fast, hard?

Donahue: I’ve seen them throw cameras at acts. Their purses, anything.

Gleason: Why do the acts do it?

Spector: Mother needs a little money, get on the road, work a little bit, get out of town.

Donahue: And they get ego satisfaction out of it, just as any performer does.

Gleason: But the frustration of them not being able to make their music or their words heard-

Spector: That’s probably why the Beatles don’t tour any more.

Donahue: One aspect of the business that’s rapidly changing is that ballrooms like the Fillmore and the Avalon have been giving these people enough consistent work–to be good, you’ve got to play, you’ve got to rehearse. I think the groups, particularly in San Francisco, have been in a bag where they would rehearse a lot, they would work. A lot of them live communally. They get a lot more time to work that way and they get exposure. Remember, rock ‘n’ roll groups didn’t have any place to play up to six years ago because nobody was holding shows. The show we held at the Cow Palace was the first large successful rock show that had been held in this country.

Spector: I used to go to the Cow Palace all the time and I used to have no trouble getting in, but last night I went to the Avalon Ballroom and then I went to the Winterland. The Avalon Ballroom. I walked in andI fell down because I tripped over four people who were laying on the floor. That had never happened to me before, you know, at a rock ‘n’ roll show. I didn’t know where they were. I was looking straight ahead. I had no conception there’d be anyone on the floor, and when I was down there everybody said, “Isn’t it groovy down here?” Guys laying on the floor! I have a friend, associate, bodyguard, what do you want to call him, who speaks every language and he has never seen anything like this, and he’s been all over the world.

Donahue: The ballroom scene is a big change. I ran dances years ago–not that many, I was just a kid-but at the Fillmore in maybe ’63, you wouldn’t see a white face in the audience. They were a different kind of dance. When I go to the Fillmore and see Bill putting out barrels of apples for the kids, the thing that always hits my mind is, if I had ever done that at a dance, they would have killed each other with the apples. Because they were on a completely different trip. I used to run a dance in Sunnyvale. I started sweating when I walked in the front door and I was in a paralysis of fear by the time I hit the stage. The toughest kids I’ve ever seen. Week after week they’d wipe out the cops and the cops kept coming back and they kept ruining the dance, but on one Friday night they totally wrecked two patrol cars and forced eight cops to the hospital. The hall was owned by people who were big in the town and it never got in the papers or anything like that, but the dances were a different scene. There was not as much love around, I guess.

Spector: One night when I was in the Teddy Bears-that was a long, long time ago-_we used to go out to El Monte, you know, terrible place. You know, the crowd would sit there and the guy would come out and say, “And now here they are, number one, the Teddy Bears,” and nobody said a word. Just looked at you real mean! They just sat there and all of a sudden they’d start to run to another side of the auditorium and I asked “What happened?” “Somebody stabbed somebody over there.” Then they’d all run back to the other side. And then back again.

Donahue: If you ran dances in those days, and it wasn’t very long ago, you could figure on the stabbings, the fights, they were just the standard things.

Spector: On a Dick Clark hop in Philadelphia, they carried some girl out. I said, What happened?” and they said, “Somebody put a firecracker in her ear.” Put a firecracker in her ear? What kind of a joke is that?

Donahue: That was when we used to run dances that were all based on records. There were no live groups. You had a record player and you played records and those people danced. We had six or seven acts come and lip-synch their records and people would watch them. But the West Coast never had a record hop scene. Even in ’61 when I came out here, there were dances, there were dances with bands. The bands were pretty bad, but they were the best ones around.

Bonis: What would happen if you had a group come out and lip-synch in the Fillmore, Bill?

Graham: They’d get all those apple cores you were talking about before. This thing is always brought up “Why no trouble?” I think the main difference today is that it means a little more to them. They are much closer to the music than they were a few years ago. The rumble was the big thing then, and the broads. Today, you talk to a knowledgeable, real hippie, not the other kind, and he’ll tell you what group is where. Stevie Winwood left The Spencer Davis Group on a Tuesday morning. San Francisco knew about it about 30 seconds later. The network is incredible in this business. Kids in the street know. I’ll put down the phone and feel very grateful to my God that we’re going to spring a surprise and bring so-and-so into town. But they know. I don’t know how, but they know.

Gleason: What’s a good contract for an artist?

Bonis: Are you talking about a recording contract?

Gleason: Yes, how does an artist protect himself?

Spector: Look, I’ve had my troubles protecting myself, I can’t worry about that artist anymore.

Gleason: You’ve been on both sides of the argument.

Spector: You can protect yourself. I mean, in the end, the courts always uphold the contract, because the Constitution of the United States is a contract for the people, so if they don’t uphold contracts, you have no law and order. Five per cent now is everybody’s standing fee. What’s ridiculous now is all of these groups are getting ridiculous advances. I mean, when they were selling the Jefferson Airplane, a man named Mathew Katz came down there and he wanted all kinds of things. He wanted 20 thousand advance. The Jefferson Airplane requires a little work, you know. And the Buffalo Springfield wanted 20 thousand and the Spoonful wanted 30 thousand and 20 thousand and 15 thousand. Their managers are ridiculous, You used to be able to get a record that was number one in 18 cities for five thousand, you know. You’d pick it up and could distribute it. Today you buy an unknown group that you don’t know anything about.

Donahue: Yeah, that situation’s just going to get worse, too. The acts have gotten to the point now where they get the big advances and now they are thinking, hey, I don’t want an advance. I want real money. And you’re going to have competitive bidding for acts like you do for a professional football quarterback.

Graham: That’s exactly the point. It’s a much bigger business now and there are many more groups and there are more record companies. There are just more dollars.

Gleason: There is another thing that enters into that,and that’s the fact that up until recently most record companies allowed the artists who were signing with them to infer from the discussion that the advance was actually a gift, a bonus, whereas it never was; it was an advance against royalties, like a drawing account for selling Fuller brushes, or whatever. And now everybody’s hip to this.

Donahue: Actually, their problem, too, is that everything today is a group. So that means your five percent or six per cent or whatever, is being split between four and five people or more. You take an act like The Lovin’ Spoonful and I’ll just give some guesses on what they’re doing. They’re with Kama Sutra and Kama Sutra releases their records to MGM for probably a nine per cent deal–I don’t think it’s any higher than that. Out of that Kama Sutra as the record producer pulls one or two per cent; Erik Jacobson who does the actual production on the records is in for a percent or two, so are Koppleman and Rubin who are in there through Erik, and then they are paying off another group and by the time it got down to the Spoonful the percentage was much lower–maybe in the beginning only two or three per cent. They are in a much better position where they’ll get paid a much higher percentage. I have no idea what the Beatles get.

Gleason: That’s nine per cent of the gross?

Donahue: That’s nine per cent of 90 per cent of 100 per cent. Figure that one out.

Gleason: When you speak about a record being number one in 18 cities, how many actual copies of that record are sold?

Spector: It depends. In the old days when you bought a record, like in 1958, records were really million sellers. You’d really sell a million or a million and a half. You don’t have many of them today because the Beatles absorb it, and the Monkees take so much of the dollar away. Motown takes so much of the dollar.

Donahue: A pretty big record will sell in Philadelphia alone maybe a hundred twenty, a hundred thirty thousand copies.

Spector: And today, people like myself are really not even needed. These groups want complete creative control. They want to do everything themselves. They want to make their own covers, their own this, their own that.

Donahue: I think there is a reason for that though, but it doesn’t apply to you. It applies to a lot of others. What has happened in most of your major record companies is that in 1956 they hired a bright young boy as an accountant and time passes and they want to promote him and all of the sudden in ’67 he’s in charge of artists and repertoire and he has no idea what to do. He has no background in that area whatsoever, and this applies to practically all of your major record companies. One of the biggest record companies in the country is RCA Victor and there is nobody who is more backward, more ignorant of basic promotions or what’s happening in the record business than RCA Victor. And you just start down through the line through the majors. The bigger they are the dumber they are, for the most part.

Spector: In ’62 the business was 95 per cent morons and it’s gone up since then.

Gleason: When a record gets in the top ten now-

Spector: Well, you can’t tell-some people tell me they have sold 800 thousand; some tell me a million, some tell me seven or six hundred thousand.

Donahue: I’ve got a record that’s 15 or 16 in Billboard this week. It’s one that our production company has. It’s 59th Street Bridge Song by Harper’s Bizarre. It’s 15 and it’s sold 210 thousand so far.

Spector: The big difference is when you get way high.

Donahue: Yeah, when you get in the top five, then you’re really cracking into big sales. There aren’t as many million sellers, per se, as there were before.

Bonis: Don’t forget there are seasonal differences. If you have a number one record at a certain time of the year when the record industry is very slow generally, say the summer time, a record can be number one in August, but if that record was released in October, say, that record selling the same amount of copies would only be number 19.

Donahue: I think this is the major change. Twenty years ago a song was a hit for a long time. The Lucky Strike Hit Parade might have had the same song in their top ten for eight months, nine months, ten months. When the Top 40 radio scene finally came around, in the middle ’50s, they were playing at that time maybe a hundred, hundred-twenty records at a station. So they decided to narrow down the number of records they were going to play, then it became the big numbers game of how many do you play. And what has happened is that there are more records selling today than there were in those days but you sell fewer of individual records because there is a vastly greater number of records being released. Records are hits for a much shorter period of time. Also, as long ago as ’47 and ’48 there were always two records of a hit song.

Spector: The Chords and the McGuire Sisters.

Donahue: Yeah: The Chords might sell a million and the McGuires sell 800 thousand. They would stay right close to each other. Every hit had a couple of versions that sold almost as well.

Gleason: What about albums? Do they sell as much as single records?

Donahue: There are certain albums that outsell singles, particularly in San Francisco. But you don’t know about it because the radio stations don’t have the guts to play them. I know Donovan has had albums in this town that have outsold single records, that should have been in the Top 10. But in most of these radio stations, the program people don’t have the faith in their own ear. They are afraid to go into an album and play the guts out of it. They are afraid somebody will tune out if they play the wrong one. They live in that kind of hysteria.

Gleason: When you have a hit single and you put the single in an album, what proportion do you sell over again?

Spector: That’s the phenomenal thing about the Beatles, and Herbie Alpert and all those things. You’d think that it wouldn’t sell, but it sells three times as many.

Bonis: In this country. In England if you do that, they’ll crucify you. Each country has its own problems. For instance, the Beatles wouldn’t think of sticking a single into an album because the English public just wouldn’t tolerate it. There’s another thing that happens in England that happens in a lot of countries but doesn’t happen here. If a Donovan album is selling enough to be out on the singles chart, in England the album would be on the singles chart. Revolver, number seven. On the singles chart. Here, there’s a singles chart and an album chart.

Spector: When the Beatles first came out, they were just monsters. They had to be recognized as the leading single, the leading album, the leading everything.

Donahue: Another way the business has changed is that it used to be that when you had an act, you put out a record and you got a hit. You then put out an album. And the album consisted half the time of your hit, eight other things you hurriedly recorded and three things you tried to make singles and didn’t turn out. If you went into a studio and you tried to cut something that didn’t make it, you’d say, well, put it in the album, Now, you go in and make an album and each cut is a polished gem. You’ve worked it out, and you may release the album before the single, and the single will come out of the album. The whole thing has been reversed, but the record-buying public is profiting by it because when they buy an LP today, they are getting a far better product. There is more product out now, too. I’m 38. When I was a kid, there were three or four record companies who each put out a record or two a month. I mean, that was it. That may be an exaggeration, but it was close to that. Now you have a situation in the pop field where you are getting maybe 200, 250 new records every week. There’s a lot of product coming out and a lot of it is good product. More people buy more records.

Bonis: I think proportionately we have the same amount of records sold, except it’s spread out over a greater number of records, that’s all.

Gleason: Now, the Beatles’ first records were out in this country for a long time before they actually hit, weren’t they?

Donahue: Right. We played the Beatles’ Please Please Me on KYA for about six weeks. Nothing happened to the record. It did not sell. It was a year later the record was number one.

Gleason: Why?

Spector: If we knew why, we’d be the Beatles; the five of us. Right here we’ve got a group.

Donahue: The Senior Citizens. I think part of it was that the whole public relations campaign hadn’t been pulled. People hadn’t been told that, you know, this is where it is at. And Epstein hadn’t gotten around to that. The thing that was done in this country before the Beatles made their first appearance, before their records were ever started, was phenomenal, in the sense that you would watch the television newscast and almost every night there was something on there about the Beatles that the Beatles publicity and promotion people had inserted because they were at that time phenomenally successful in Europe.

Gleason: Before the Ed Sullivan show.

Donahue: Even before the Sullivan show.

Bonis: The Stones, once their management problems were over with, timed their appearance on the Sullivan show so that it coincided with the release of their single. This is something, of course, that the Beatles did right from the beginning and smartly used it to get national exposure for the single and then the DJ’s of course were playing it a week before the Sullivan show and then, of course, the Sullivan show helped, but the Stones used to come in and do a Sullivan show at any time, not doing it at the right time. The first record they ever got to do on the show the week after they released it was Satisfaction and of course it was the best record they’d done and it then helped put that record over much, much faster than they would have.

Donahue: Of all the acts, the Rolling Stones, to me, are the best in-person performers, consistently, because they put on a tremendous show and they come off, but I think they are big enough now that they didn’t have to go on the Sullivan show a couple of months ago and cop out by changing the lyrics of their song. They should have told Ed Sullivan to go to hell.

Bonis: They did. They were threatening to go home, take the next plane home and forget the whole thing. In the end, they did it anyhow, they did change the words and copped out completely.

Gleason: How much actual censorship of records is there in the radio business?

Spector: Today, ail the disc jockeys are images, all their power’s been taken away. There’s a guy who is a program director, and he hasn’t got time to see anybody. And he has no ear, and he doesn’t care how good the record is. He only cares where it is selling and how much it is selling. You’re fortunate in San Francisco–you’ve got one of the largest local markets I’ve ever heard. I mean I heard a disc jockey on KFRC last night play a Chuck Berry record and he said “Welcome to town, Chuck.” I’ve never heard that in New York. Never heard it in Los Angeles. Never hear that informality, that real “Hey, Chuck, nice to have you.”

Bonis: The way to lick this is like in New York City. When the FCC forced the FM-AM stations to not broadcast the same broadcast so many hours a day, WOR-FM in New York went rock, but without the Top 40. In other words, when a record comes out, if the DJ likes the record, he plays it. He doesn’t have to wait until the following week when the committee meets and decides whether it is worthwhile or not. Say a Simon and Garfunkel tune, where he says “I smoke a pint of tea a day,” that’s not censored. That goes out on the air. The station was started about two-and a half or three months ago, and when the first ratings came out they found they had the largest FM audience in New York’s history. The listener level is such that it’s the young adult, college age and on up, not teenagers, because most of them don’t have FM. But “on up” apparently according to the survey, went up to about 50, 55-year-olds. But the group listening to the station was predominantly the collegiate group and the station itself is the kind that would say “Welcome to town, Chuck.” There is no required list of records; the DJ has a lot more freedom there. I don’t know how long it is going to last, mind you. But apparently it is working and it’s successful and they play the Top 20 pop tunes in the United States, they play you the Top 5 in England, they play you the Top 5 rhythm and blues tunes and they play the Top 5 country and western tunes, and the station became the number one FM station and on the first survey they were seventh most listened to station in New York overall. From what the indications were when I saw the Nielsens, it looked as if it would go up three or four more notches after that survey. I don’t know what’s going to happen. That isn’t a normal case.

Gleason: With the tight playlist and program directors dictating what can be played on the air, how do you bust into it with a new record?

Donahue: About the only way you can do it nowadays is to break them out in markets like Sacramento, Stockton, Fresno. It gets harder and harder to break them in a major town because everybody’s waiting to hear what’s happened in some other town. Nobody wants to take the chance because they have no guts, no brains, no talent and nothing to offer.

Graham: We spoke to a disc jockey from WABC in New York about a particular group and their new record. His name is Cousin Brucie. He said, “Crazy, crazy, out of sight, man, love the record, crazy, psychedelic, wow!” But he said in order for this record to be played through normal channels they first have to get heat waves and vibrations from other states, then they have to meet with the program director, and he and Cousin Brucie and another executive with a larger hat sit down and vote every Tuesday.

Bonis: On the vibrations?

Graham: On the vibrations.

Spector: People put that down, but really it’s that way in every industry. How many producers of big television shows have their wives say “I don’t like that show,” and that show is off the air. It’s nothing new. That’s why there are so many young disc jockeys today. I mean, young guys like 19 and 20 coming along just really don’t know anything. Like Tom says, you go in and they turn you on and you’re on and that’s it and they shut you off and you go out of the studio. They don’t understand music.

Donahue: I think there will be a change someplace along the line. Some radio station owner will have the courage to come up with a new kind of radio. The Top 40 radio format dates back to about 1955. Some people in Kansas City started it. Nothing has really changed since then, they are all doing things they have no idea why they do because that’s the way it’s been always done. Some place along the line somebody will break it, will come up with an imaginative, creative format. And as soon as that’s successful, 2,000 stations throughout the country will start doing that and wear it out in no time. But it’ll change because it can’t stay this way. It’s too boring. Now stations choose records by following publications like Billboard, Cash Box, and Tempo, The Bill Gavin Report, newsletters. Anything of that nature. They hope they’re guessing right because they are afraid to guess themselves. They call the record stores and they get the reports. They’re pretty bad, I mean, most of it’s guess.

Gleason: The Billboard Chart is put together by giving free subscriptions of Billboard to record stores if they will mail in a thing every week, so it’s always about three or four weeks behind the actual sales, and what happens is that if you conduct a telephone survey of record dealers and you ask them what’s the best selling record since last week, you don’t really get the best selling record for the last seven days–what you get is the one he has sold most recently. He sold three copies of it this morning. That’s a big record for him, you know, like he’s going to sell 50 this week, he thinks, and he forgets that he sold 27 copies of something else in the previous five days. It’s very inaccurate.

Donahue: Rigging is still tried from time to time, but it isn’t very effective. You can’t hype a stiff. You can sometimes force a record if you have a record that is right on the edge. I’ll give an example: Nancy Sinatra had a record recently called Sugartown. Really rotten record, but she’d just come off two or three hits and the record got enough sales and the company kept enough pressure on (her father owns half the company, you know) until finally the record came through.

Gleason: One of the best illustrations I know of that whole business of hyping radio stations and dealers and everything on record sales was the time that an agency in New York took out a tour of sort of a variety show and the wife of the president of the agency was a girl singer who has long since disappeared. They played 56 cities east of the Rockies and in each city they spent an average of $2,000 promoting the concerts. (She wasn’t in the concert. Nat Cole was in the concert.) They spent $2,000 in each city on radio publicizing the concert and the deal was, that if you got the radio time, you got the two grand for your station if you played the girl’s record. So for a period of about 90 days, during the course of this tour, the whole country east of the Rockies was listening to this terrible record and they never sold five copies of it.

Bonis: You can’t hype a dead record.