First off, let’s admit it: Comic books are fun. And that may explain America’s resistance to comics as a “serious” art form. Our national temper includes a Puritanical thread that looks askance at anything that might be fun.

Then again it could have been the lingering effects of the anti-comics crusade led by psychiatrist Fredric Wertham from 1947 until—well, basically until he won. After he published Seduction of the Innocent in 1954 (and wouldn’t that have been a great title for a comic!) there was a Senate inquiry into comics as a cause of juvenile delinquency, comic-book burnings, and a code imposed on the industry that put a number of publishers out of business. (Prompting Harvey Kurtzman to publish Mad as a magazine, and thus avoid the stricter comic code.) By the time Wertham was done, the view of comics-readers as children, actual or intellectual, was set firmly in the popular mind.

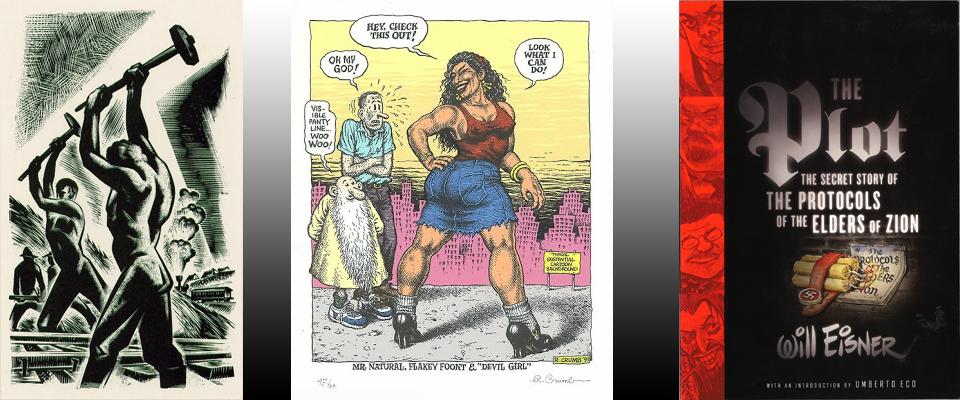

To some artists, of course, this was like a free pass. Kurtzman’s stable of brilliant satirists for one, and the almost unepithetable R. Crumb, for another. To be fair, a lot of the art world of the late ‘60s did indeed recognize Crumb’s artistic genius and at least tacitly agreed that the comic form was the best genre to showcase his exuberance, crassness, iconoclasm, and obsession with women’s legs.

But for the most part, the crusade had slowed development of the art form in the United States (and Canada—if anything, Canada’s code was even harsher) into something that serious adults might take intellectual pleasure in. Thus, in 1978, when Will Eisner released his lovely, poignant collection of tales set in a Jewish tenement in New York, A Contract with God, the marketing department of his publisher coined the term “graphic novel” to signal that this was serious stuff. And serious stuff it is—but there’s a very good reason that the annual award in the comic industry is called the Eisner Award.

It wasn’t until the 1986 publication of the first half of Art Spiegelman’s Maus that a great comic book openly admitted to being a comic book. Sure, lots of people still insist on calling it a graphic novel: The Pulitzer committee, for example, when it granted a special award to both volumes in 1992. The New York Times review of the completed set in 1991 actually begins “Art Spiegelman doesn’t draw comics.” And most of the college campuses that study it as literature (as opposed to pop art) still refer to it as a graphic novel. But Spiegelman himself calls his saga of the Holocaust a comic, and his decision to portray all of the characters as animals and to place the action in small sequential frames certainly bears that out.

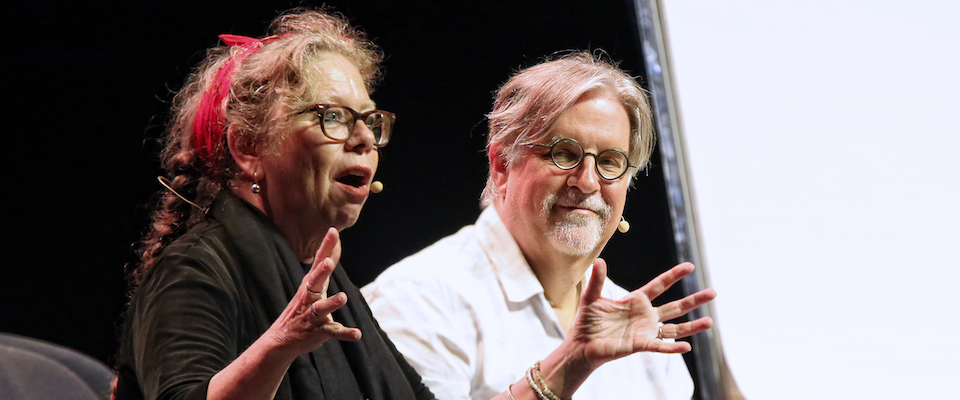

Spiegelman is currently on tour, perhaps unavoidably for an author of certain years and reputation. But where anyone else would be “on the lecture circuit,” Spiegelman has pulled together his own Vaudeville act. In addition to talking about comics and showing examples of his own and others’ works, his backup jazz combo led by Phillip Johnston provides atmosphere and the odd musical sting. The show, called WORDLESS!, is touring select U.S. cities this fall and was originally commissioned by the Sydney Opera House—which is how you can enjoy some snippets of the actual spiel in this trailer.

In the clip, you may enjoy his quip denying paternity of the graphic novel. And it’s true he wasn’t the progenitor. But he did help it out of the awkward teen years and into college, so maybe we can call him the Stepfather of the Graphic Novel.

As the name WORDLESS! Implies, the show mainly concerns those true graphic novels that preceded today’s comics for grown-ups. (Not to be confused with “adult comics,” which never had much of a problem ignoring the code.) Interesting tidbit: Publisher Hugh Hefner originally wanted to be a comic artist and has championed the medium, not least by including some of the best cartoonists of the day in Playboy from the very first issue. The appropriately inappropriate subjects of Playboy cartoons are strong enough stuff even to raise a few eyebrows at the Berkeley show, hosted by Cal Performances as part of their new Berkeley Talks series. Spiegelman spends a fair amount of time on the American Lynd Kendall Ward, who was inspired by earlier European woodcut artists to produce six wordless novels entirely in woodcuts of his own making. Refreshingly, Spiegelman admits that as novels they really aren’t that great. They’re often blunt-instrument socialist allegories in a style he likens to a cross between bucolic and Tom of Finland. But at their best, Ward’s novels convey a depth of despair and hope that explains how they inspired a generation of cartoonists, Spiegelman clearly among them.

It’s understandable, if a little disappointing, that the show doesn’t say much about Maus. At least not directly. After all, the Artie Spiegelman figure in the second volume feels hounded by reporters and explains to his therapist how uncomfortable he is talking about the work. It would also be interesting to know who he sees as promising in the current crop of artists.

On the other hand, having provided a good overview of the development of the medium, it’s nice to think he’s providing his audiences with the tools to make their own decisions about the artistry of what they see.