When filmmaker Violet Du Feng, M.J. ’04, returned to China after earning her master’s degree at Berkeley, she was struck by a kind of gender inequality she hadn’t noticed before. In modern Chinese society, Du Feng realized, women are expected to fulfill traditional roles of raising children and serving the extended family while also succeeding professionally.

“How do we juggle between all of that?” Du Feng wondered. “All these pressures are on us and made me feel very trapped.”

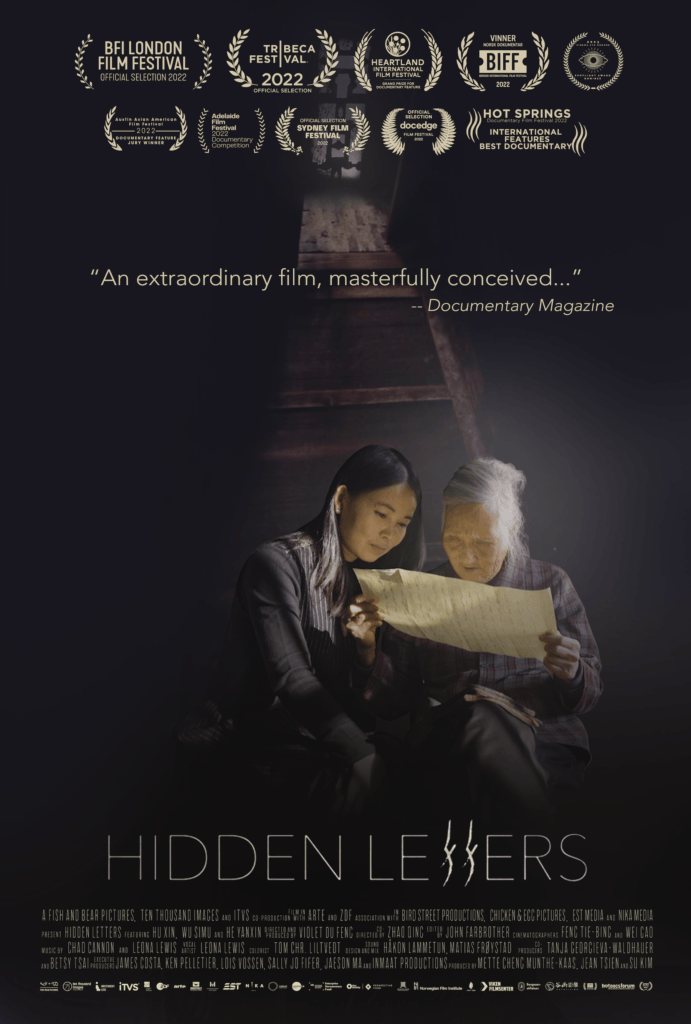

When she learned about a secret, women-only language called Nushu (literally “women’s script”), Du Feng knew it was the perfect vehicle to discuss women’s lives in China today. The result is a nuanced take on Chinese sexual politics in her latest film, Hidden Letters, which was shortlisted for the Oscars in the Documentary Feature Film category.

Nushu is a written and oral language developed by women in the Jiangyong County of Hunan, China. It rose to prominence in the 19th century as a means for women to communicate without their husbands’ knowledge. This was at a time when women’s feet were often bound and they were denied education.

While women achieved greater equality under communism (one of Mao’s famous dictums was “Women hold up half the sky”), the society remained fundamentally patriarchal and Nushu has persisted in today’s more capitalistic China. While Nushu is no longer secret, many women still turn to it for the solace it provides.

Hidden Letters follows two women, Hu Xin and Wu Simu, and their relationship with Nushu. Hu Xin is the youngest government-certified “inheritor” of Nushu. Yet, because she left her abusive husband, her life is marked by failure. “My achievements don’t make me a good woman. As a woman, I’ve failed,” Hu Xin says.

Wu Simu starts the film engaged to a man who tells her she must give up her “hobby” of Nushu in order to fulfill her duties as a wife.

While both women turn to Nushu for comfort, it’s no longer the women-only sanctuary it once was. Men instruct Hu Xin on how to write the characters they can’t read. A marketer proposes to brand potatoes with Nushu. One man says the Nushu script on his clothing makes him feel like women are watching over him. Another says that the value of Nushu is that it instills the essential qualities of women: “acceptance, obedience, resilience. As long as women have these three values, we’ll have a good society.” Six men cutting the banner at the opening of the Beijing Nushu Center underscores the feeling that Nushu is losing its feminist spirit.

Throughout the film, Du Feng is subtle in her criticism; a lingering shot on the women’s quiet faces reveal their reaction. An older woman laments that “whatever [Nushu] is now has nothing to do with the Nushu we had.”

“I want my films to be seen both in the Western world and also in China. Because if a film I make about China cannot be seen in China, then what is the point?” Du Feng said. “I truly believe that changes happen from within.” The film is currently awaiting censor approval in China.

Du Feng says her primary goal with Hidden Letters is for both men and women to reflect internally on gender equality rather than change policy. But Du Feng’s storytelling has led to reforms: her 2015 documentary Please Remember Me changed the way Alzheimer’s patients are treated in China.

Asked about the Oscars, she sighs. While it was nice to be shortlisted, she felt like an outsider. But she takes pride in the fact that Hidden Letters was produced by a team of all women.

Perhaps the film and Du Feng’s goal can be conveyed by this Nushu poem: “Beside a well, one does not thirst. Beside a sister, one does not despair.”