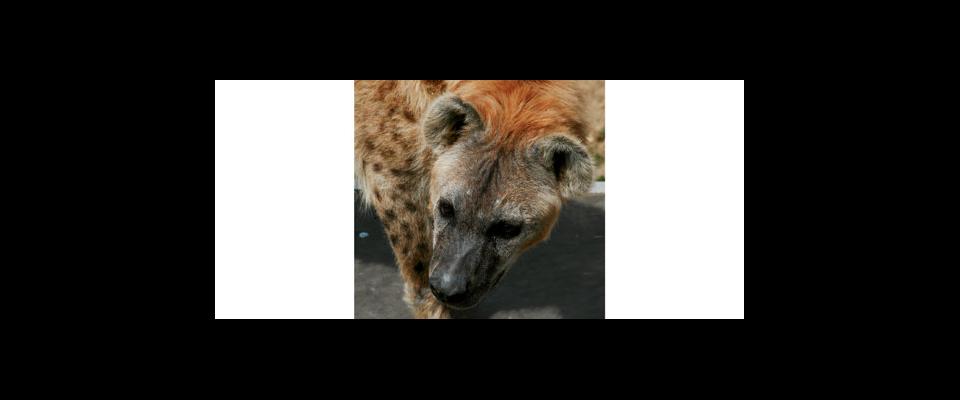

What Berkeleyite has not heard them, hooting and gibbering at twilight across the East Bay hills? As the romance novelists might say, it sent a frisson down your spine, made you somehow feel that you were an early hominid on the African veldt, vulnerable to large and toothy predators.

But soon Berkeley’s spotted hyenas, and their haunting crepuscular serenades, will be gone. After 30 years, funding for the captive research colony—the only of its kind in the world—has run out. Once numbering up to 54 animals, the colony has dwindled to 13 remaining hyenas soon to be dispersed to zoos and refuges across the country. Some may even wind up at Disney’s Animal Kingdom in Florida. That would be ironic: Although Disney animators famously based their depiction of the villainous buffoons in “The Lion King” on their observation of the Berkeley hyenas, colony project co-founder Laurence Frank, an associate emeritus of UC Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, loathes the anthropomorphizing of animals in general, and “The Lion King” in particular.

In its three decade run, the colony has been the basis of groundbreaking research on the relationship between hormones and behavior. Hyenas are unique among mammals in that the genitalia of the females resembles male genitalia, with a large clitoral “pseudo penis.” Female spotted hyenas are bigger than the males, and dominate social relationships.

Frank and integrative biology professor emeritus Stephen Glickman started the colony with animals that Frank brought back from the Masai Mara region of Kenya.

“With the help of Masai friends, I was able to capture 20 newborns in the wild and bring them to Berkeley,” Frank emailed from Kenya, where he continues his predator research and conservation work. “We bottle-reared that first cohort. They proved to be wonderful animals, remarkably tame, easy to work with, and just huge fun. They are so highly social, so similar in many ways to humans, and so much more tamable than wolves, that I am convinced that, had any animals ever been domesticated in ancient Africa, we would have very friendly hyenas today rather than dogs.”

Esteem for the captive colony extends well beyond Berkeley. The hyenas have been studied by researchers at many other universities, and are linked to significant findings in multiple fields. In an article published in Berkeley Science News in 2011, Sarah Jones, then a graduate student at zoologist Kay Holekamp’s lab at Michigan State University, wrote that the colony provided insights to “…a broad range of interests – whether you’re into immunology, psychology, evolutionary biology, or just weird genitalia…Advances in these fields have been made with the help of the Berkeley hyenas.”

She observed that while field research on wild hyenas is valuable, it’s also difficult to pursue.

“The availability of captive hyenas has provided opportunities to validate and extend field studies,” wrote Jones. “For instance, we can we can only dart hyenas in the field every few years since being shot in the butt too frequently can make the hyenas wary of us—which is problematic when we are trying to casually roll up and observe their behavior. Access to the captive colony allows us to take blood and tissue samples more frequently from the same animal.”

But not everyone is sad that the Berkeley colony’s number is up. Animal rights advocates hail the closure, claiming the colony’s animals were subject to cruel treatment.

“It’s false to suggest that the experiments conducted on these hyenas weren’t harmful,” said Justin Goodman, the director of laboratory investigations at People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA). “They were shot with tranquilizer darts. In some cases, female hyenas were deliberately impregnated just so researchers could cut out their unborn cubs to observe genital development. The colony represented the traditional and dangerous ‘conservation’ argument that the ends justify the means, that you have to harm the individual to save the larger group. That kind of thinking leads to all sorts of atrocities.”

But what about the fact that spotted hyenas are among the most social of carnivores, and that breaking up the colony will cause the animals unwarranted stress?

“The researchers created this problem,” said Goodman, “and they have the moral obligation to deal with it. There are accredited sanctuaries that could take (the whole group), and the university should provide the resources necessary for keeping them together.”

Frank, for his part, ripostes that PETA is clueless about both conservation science and hyenas.

“The arrogant ignorance of PETA and their ilk about animals is rivaled only by the ignorance of the climate change deniers and creationists,” Frank emailed. “I understand wild hyenas very well, and have always been gratified at how happy and well-adjusted the Berkeley hyenas have been. They have lots of space, good food, and plenty of hyena company. To know hyenas is to love them, and the Berkeley animals have always been cared for by people who love them deeply. The dispersal of this colony is a blow to our understanding of the complexities of nature.”