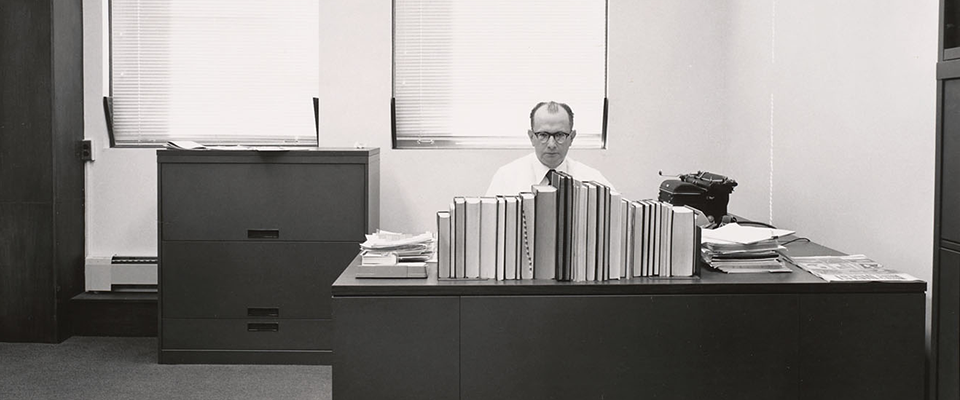

Sometimes the rough draft of history isn’t a newspaper, but a pile of them. Along with moldering manuscripts, reams of correspondence, posters and handbills, memoranda fastened together with rusty paper clips, all of it stuffed into decaying cardboard boxes. Rodents may or may not be involved.

It’s a scenario that’s only too familiar to the curators and archivists of the Bancroft Library. Home to 690,000 volumes, 175 million manuscripts, nine million photographs, two million digital files, 117,000 microforms, and 25,000 maps, the Bancroft is one of the nation’s great research institutions. Every year, thousands of scholars come to mine its collections.

The library, in short, is a capacious reservoir fed by a robust and unceasing stream of manuscript

material.

The Bancroft boasts the richest primary source material for a wide range of subjects, from California history and politics to Latin America, Western Americana, and Mark Twain. Other significant collections include the Tebtunis Papyri, the largest assemblage of ancient papyrus texts in North and South America; Medieval and Renaissance manuscripts and incunabula; archives of the nation’s seminal environmental and conservation organizations; and roughly 200 separate archives associated with the history of science and technology. The library also supports the Oral History Center, which conducts, collects, and preserves interviews.

Keeping everything up and running is a Herculean—maybe even Sisyphean—task, one that the hushed interior rooms of the Bancroft belie.

The library is constantly adding to its collections, and staffers spend long hours and preserving voluminous backlogs of material. The library, in short, is a capacious reservoir fed by a robust and unceasing stream of manuscript material—measured in linear feet of cartons. In 2017, the library received 1,734 cartons (2,167 linear feet, when the boxes are stacked end-to-end), including 855 cartons of papers from former Senator Barbara Boxer. The intake was slightly down in 2018: 926 cartons, comprising 1,158 linear feet.

But what’s the provenance of all this material? Collections come to the Bancroft through several avenues, says Lauren Lassleben, Bancroft’s accessioning archivist. Known articles of significant value are sometimes purchased outright. More often, existing collections are added to over the years from long-established sources—materials related to the Sierra Club, for example, find their way to the Bancroft through the club’s various semi-autonomous chapters, administrative arms, and even prominent individual collectors.

“On top of that, we have such things as their summit registers—the books the club maintains on peak summits that are signed by climbers,” says Lassleben. “We don’t mix everything together. They’re all maintained as separate collections.”

Sometimes an item of particular interest comes in “over the transom” from a private citizen. That can be delicate, says Lassleben. A potential contributor can arrive with the usual boxes of jumbled papers and aging pulp, from which the curators and archivists must winnow out the few gems.

Caution is necessary because context is critical when it comes to historically significant documents. Staffers take pains not to change the original order of the material.

“Sometimes people can get huffy if you don’t take it all,” Lassleben says. “We’ve found that’s more often the case with the heirs or associates of a primary source, rather than with the direct source. If people are donating their personal collections, they tend to be less sensitive than their relatives.”

Other times entire collections are donated.

“David Brower [the famous environmental leader] regularly loaded up his station wagon with documents and drove down the hill to deliver them,” recalls Lassleben. “And we had a wonderful experience with Gus Arriola, the creator of the comic strip, Gordo. He donated all his strips to us, and when we’d meet him in Carmel where his fans would all gather around as we had lunch, and he’d regale us with fantastic stories, like fighting with the Marx brothers for his wife’s hand. He inscribed his final strip with, ‘Farewell, Carmela—I’m moving to Bancroft.’”

When archivists are notified of material of possible historical value, their first mandate is to investigate—procedures that evoke cleaning out dusty attics more often than evaluating exquisitely illuminated manuscripts in clean and well-lighted places.

“Sometimes things are well-organized,” says Lassleben, “but more often they’re not. Typically, it’s a situation where the creator of the material died 15 years before, everything was piled into cartons and nothing has been touched since. The heirs or executors don’t know what’s in them. So we move carefully.”

Caution is necessary because context is critical when it comes to historically significant documents, says Lassleben. Staffers take pains not to change the original order of the material.

“We have to consider not just the individual papers, but why some may be attached, why others aren’t, and why they may be arranged in specific ways,” Lassleben says.

Staffers also face inevitable challenges in processing material, says archivist Marjorie Bryer.

“You learn to prioritize,” says Bryer, “particularly when you’re dealing with hundreds of linear feet of material that must be examined, described and ultimately made available to the public. In your descriptions, you strive to impart a sense of the significance of the material in its historical context.”

Images—particularly photos—can be especially difficult.

“Sometimes you may not be completely sure what you’re looking at, or when a photograph was taken—say, an urban street scene,” says Theresa Salazar, the curator of the Bancroft Collection of Western Americana. “Are there horses? Streetcars? Utility poles? Specific makes and models of cars? What are people wearing, what are the store signs? You’re constantly looking for clues, anything that will help you confirm its place and time.”

The most immediate priority for any new material is preparing it for safe storage. Papers often arrive crammed helter-skelter in cardboard boxes, and may be damp, moldy—and buggy.

“We’ve seen some very large silverfish,” says Lara Michels, the head of archival processing, “and we can’t have them coming into the library.” Before entering the Bancroft, papers first go to a room-size freezer in Richmond where they are held at 27 degrees below zero until all insects have been killed.

The most immediate priority for any new material is preparing it for safe storage. Papers often arrive crammed helter-skelter in cardboard boxes, and may be damp, moldy—and buggy.

Freezing is also essential in removing water from archival papers. Once a collection has been purged of insects and moisture, it’s stored in special acid-free cartons. (Cardboard is acidic, and acids degrade paper.) But the Bancroft isn’t just about paper—not anymore. Like everything else, the library is adjusting to evolving technologies. It has a large store of audio-visual material, including Beta and VHS tapes (remember those?).

“Also, our digital material is constantly increasing, and we anticipate a time when most of our acquisitions will be digital,” says Bryer, “and that presents even greater challenges than paper. The sheer volume of material stored on one hard drive alone can be daunting. You can have thousands of photos, thousands of files that may or may not have curatorial value. Plus, there’s often a lot of sensitive personal information—medical or credit card records, for example. So we use forensic tools that allow us to pull out and discard private material.”

Aspiring researchers should know you can’t just mosey into the Bancroft and poke around. That said, the bar for entry isn’t that formidable. Established scholars, undergraduates, and even high school students all use the collections. All that’s needed, says Bryer, are two forms of ID and a “legitimate reason to view the materials.”

“It isn’t our job to evaluate the people who want to view our material, and no one here ever says a research topic is a stupid idea,” she says. “These materials, after all, aren’t serving their original purpose—in virtually all cases, that ended long ago. They’re living an afterlife, and our purpose is to prepare them for that afterlife, to preserve them and make them available to people who need to study them.”