The radio station we now call KALX began life as an oddity in the basement of Ehrman Hall, a dormitory on Dwight Way. It had at its disposal a collection of records, mostly classical, a couple mics, a cheap recorder, and a Corina cigar box containing the most basic of mixing boards. The year was 1962.

This was not a sanctioned operation. It was not a political statement. It was barely even art. Radio KAL was, in fact, the work of geeks; driven, visionary, persistent, highly resourceful geeks.

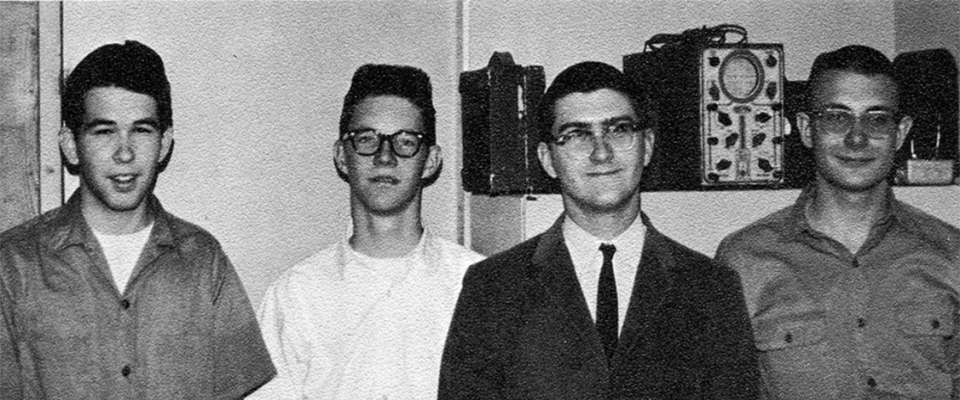

Jim Welsh, an electrical engineering major, and Marshall Reed, a geology major, were freshman roomies who lived upstairs. They talked their way into Ehrman’s basement listening rooms—intended for students to play records or practice instruments—then quietly ran cable and homemade transmitters throughout the two-year-old building, having recruited a residence-hall handyman for help with both keys and carpentry. Thus was KALX born.

“The rule there was the university wouldn’t let you do anything, but after 10 or 11 at night, everybody went home and nobody cared what you did.”

Welsh and Reed are no longer around to the tell the story, but the gospel is carried by Sam Wood (BS 1968), who joined them soon after coming to Berkeley from his hometown of Sacramento in the fall of 1963. He was an electrical engineering major, too, and he met them through yet more engineers living on his floor in nearby Unit 1.

Together they joyfully built the station from scratch by salvaging unwanted parts and equipment from various campus departments and government surplus stores. They even raided the Cow Palace following the 1964 Republican National Convention, transporting the loot back to Berkeley by overloaded station wagon. They turned the erstwhile trash into transmitters, consoles, and other components to be surreptitiously hardwired in an elaborate web of radio infrastructure inside campus basements, attics, closets, storage rooms, and walls—some of which Wood found still intact when he visited campus ten years ago for his 40th reunion.

“The products we were making we could not afford. We figured out designs by talking to people and doing work ourselves,” he said. “The rule there was the university wouldn’t let you do anything, but after 10 or 11 at night, everybody went home and nobody cared what you did. If wires somehow got into conduits, then nobody cared how they got there.”

What hooked Wood wasn’t the act of broadcasting per se, but rather this combination of mischief and ingenuity operating behind the scenes. “It really was homebrew, to say the least,” Wood recalled. Radio KAL didn’t just slip through the cracks: “We were in the cracks.”

Yet they were also ambitious—as engineers, at least. In time the station moved to the basement of Dwinelle Hall, garnered a $500 annual stipend from the Chancellor’s office, secured a broadcast license from the Federal Communications Commission, mounted a 700-foot antenna atop Eshleman Hall, and issued its inaugural signal at 90.7 FM with ten watts of power.

Meanwhile, its leaders remained committed to cultural and political impartiality, Wood said. The date of that first broadcast was October 3, 1967: three years into the Free Speech Movement and six months after massive Vietnam War protests erupted across the country and the Berkeley campus. KALX quickly became a target.

“People would come in with an agenda, radical groups on the left and the right, that wanted to use the station to rile people up. Since the area was so political, there were groups that wanted to take over the station,” Wood recounted. “The Chancellor’s office and the Regents would be horrified over this happening, and they’d shut the station down in an instant.”

“We were responsible to the Chancellor’s office, so we had to keep things pretty tame. So that’s what we did,” Wood said with more pride than regret. “We were engineers, and generally engineers are pretty conservative and don’t want to get into a lot of political dealings.

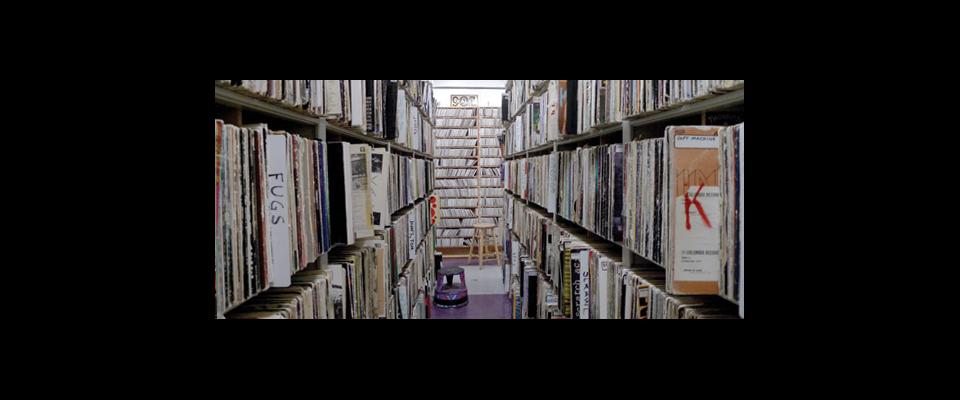

“We broadcast both sides of these things, and we kept the station neutral,” he continued. “We had the only complete set of recordings of speeches that were given on the Sproul Hall steps, but it wasn’t to editorialize. It was just, ‘Here it is, make what you will of it.’”

By the next year, however, their diplomatic run had come to an end. After serving as chief engineer, assistant manager, and general manager in successive one-year stints, Wood graduated and KALX passed into new hands. The ideologically motivated threats he had feared soon caught up with station, leading to its temporary disbanding and removal from campus on multiple occasions in the 1970s. By the end of the decade, though, it was back for good.

Now entering its 56th year, KALX is an around-the-clock, often punk-rock, student-run, fully campus-backed institution with a 500-watt signal reaching from Redwood City to Petaluma, and an online feed serving everywhere else.

Wood went on to a successful career in telecommunications design, voice and data networking, and other electrical-engineering specialties. He now lives in Los Altos, where the name of his consulting business, MSR, is an acronym borrowed from the term he and his friends used five decades ago to describe their late-night adventures scavenging and wiring for the station: “midnight supply and requisition.” The more things change, the more they stay the same.