Far-right provocateur and Breitbart News Technology Editor Milo Yiannopoulos has prospered mightily by posting screeds that his many detractors characterize as racist and misogynistic; so popular is his invective with a certain political subset that Simon & Schuster recently handed him a $250,000 book deal. The dapper, openly gay rabble-rouser is now on a college tour to flog both his book and his incendiary views, and the push-back has been considerable.

An engagement at the University of California at Davis was canceled when it appeared protests might get out of hand, and other colleges, including UCLA, have canceled his talks due to security concerns. Yiannopoulos and his supporters have characterized the cancelations as violations of their First Amendment rights.

The controversy has particular resonance for Cal, given that the university sparked the Free Speech Movement. And Yiannopulous is scheduled to speak on campus on February 1st at the invitation of the Berkeley College Republicans.

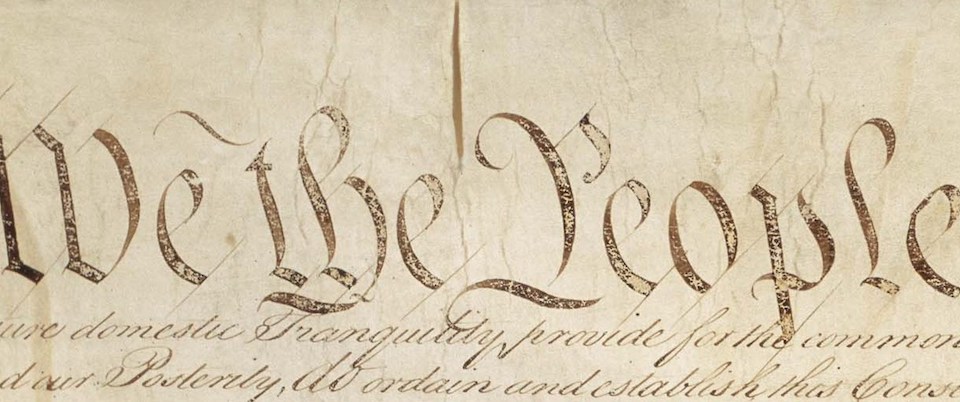

The claims by Yiannopoulos et al. that free speech rights are abrogated when an invitation to speak at a public university is pulled do warrant some investigation. Free speech, after all, is not necessarily genteel, popular, or even true speech.

Berkeley law professor Robert Cole observes that First Amendment strictures apply to state actors, not private parties.

“[The university] must maintain that neutral marketplace. It’s required to walk a very narrow path.”

“So if the question is do they apply to a state university, the answer, of course, is yes,” says Cole.

In the case of Cal, says Cole, “Berkeley College Republicans is a university-sanctioned organization, and if, as it seems, it issued an invitation and arranged an engagement in accordance with university rules, then the university must allow the event. The university’s role is to remain a neutral marketplace. It can’t cancel a speaking event simply because a speaker is considered controversial, or officials are worried that it could result in bad publicity, or things could get raucous.”

A state university, continues Cole, can only cancel an event if it meets the “clear and present danger test,” a doctrine defined by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1919. Under that ruling, free speech can only be limited by a law or agency if there is a clear and present danger to public safety and property.

Unruly protestors don’t fall into that category, says Cole, unless they begin destroying property and hurting people.

“If that happened during a campus event, then the university is required to stop them and seek discipline,” Cole says. “But it can’t do anything up to that immediate threat of disruption. It has to let the speakers speak, and the protestors protest. It must maintain that neutral marketplace. It’s required to walk a very narrow path.”

Berkeley law professor Daniel Farber agrees with Cole that Cal—more to the point, any public university—must tread very lightly indeed around free speech issues.

“The Supreme Court has emphasized that the First Amendment is intended to protect ‘uninhibited, robust, and wide-open,’ public debate,” Farber stated in an email, “so in terms of general principles, it seems to me that universities should be very hesitant to exclude a speaker or viewpoint simply because it is offensive or disruptive.”

But the clear and present danger test also implies some difficulties for public institutions obliged to ensure both free speech and public safety. Cal is requiring Berkeley College Republicans to cough up $6,372 to pay for security at the Yiannopoulos event. That might—or might not—test the requirements imposed by Forsyth County v Nationalist Movement, a 1992 Supreme Court ruling that limited the authority of local governments to levy fees on private groups using public facilities.

“On the one hand, you have to have a content-neutral basis for [any] regulation [that might impinge on free speech],” says Jesse Choper, a professor emeritus at Berkeley Law, “and on the other, your assessment must be based on the perceived danger of such speech. So in a way, you’re forbidden to make a judgment, and you’re also required to make a judgment.”

Ambiguous as the situation seems, it is clear that “speech cannot be financially burdened any more than it can be banned because it might offend a hostile mob,” says Choper. “My own view, and I think it is unbiased, is that the Chancellor’s office is between a rock and a hard place. I’m sure they assessed this fee because money is tight and I’m sympathetic to that. But I’m also sympathetic to free speech. The court is clear that you can charge a fee for speaking events, but it is less than clear on just how you determine such fees.”

Pieter Sittler, the internal vice president for Berkeley College Republicans, confirmed that his organization has been assessed the $6,000 plus fee to provide security for Yiannopoulos.

“…He has no right to be invited to speak, and no right to be immune from being disinvited.”

“Even though Milo is receiving no personal payment, this [security fee] still would’ve been a real burden for us,” says Sittler. “But the university has been extremely gracious in working with us, and a lot of groups and individuals have helped us with donations. We’re anticipating the event will go on as scheduled.”

First Amendment protection, however, does not preclude Yiannopoulos from being uninvited.

As far as claiming that uninviting Yiannopoulos would violate his First Amendment rights, states Berkeley Law Professor Ian Haney-Lopez, “…He has no right to be invited to speak, and no right to be immune from being disinvited.”

Acts convey meaning, says Haney-Lopez, and thus constitute a form of free speech.

“When universities invite someone to speak, they communicate that that person’s ideas are within the broad range of important public [discourse],” Haney-Lopez states. “Disinviting someone from speaking likewise communicates something—in this case, that the universities have come to realize that this speaker intentionally degrades people to draw attention, while offering little of any real intellectual substance. His poisonous invective is being drowned out by more and louder speech affirming humane values and inclusion. That’s precisely the ideal of free speech in action.”