Not everyone would choose as feminist hero a beleaguered wife who goes through a test of fire to prove her purity. Sally Sutherland Goldman has convincingly argued just that in her essay for the catalogue of The Rama Epic: Hero, Heroine, Ally, Foe at San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum through January 15.

“An abused wife and yet a feminist heroine, she possesses a voice that continues to be heard as a powerful index to cultural norms, anxieties and resistances,” Goldman writes at the end of her essay, “A Heroine’s Journey.”

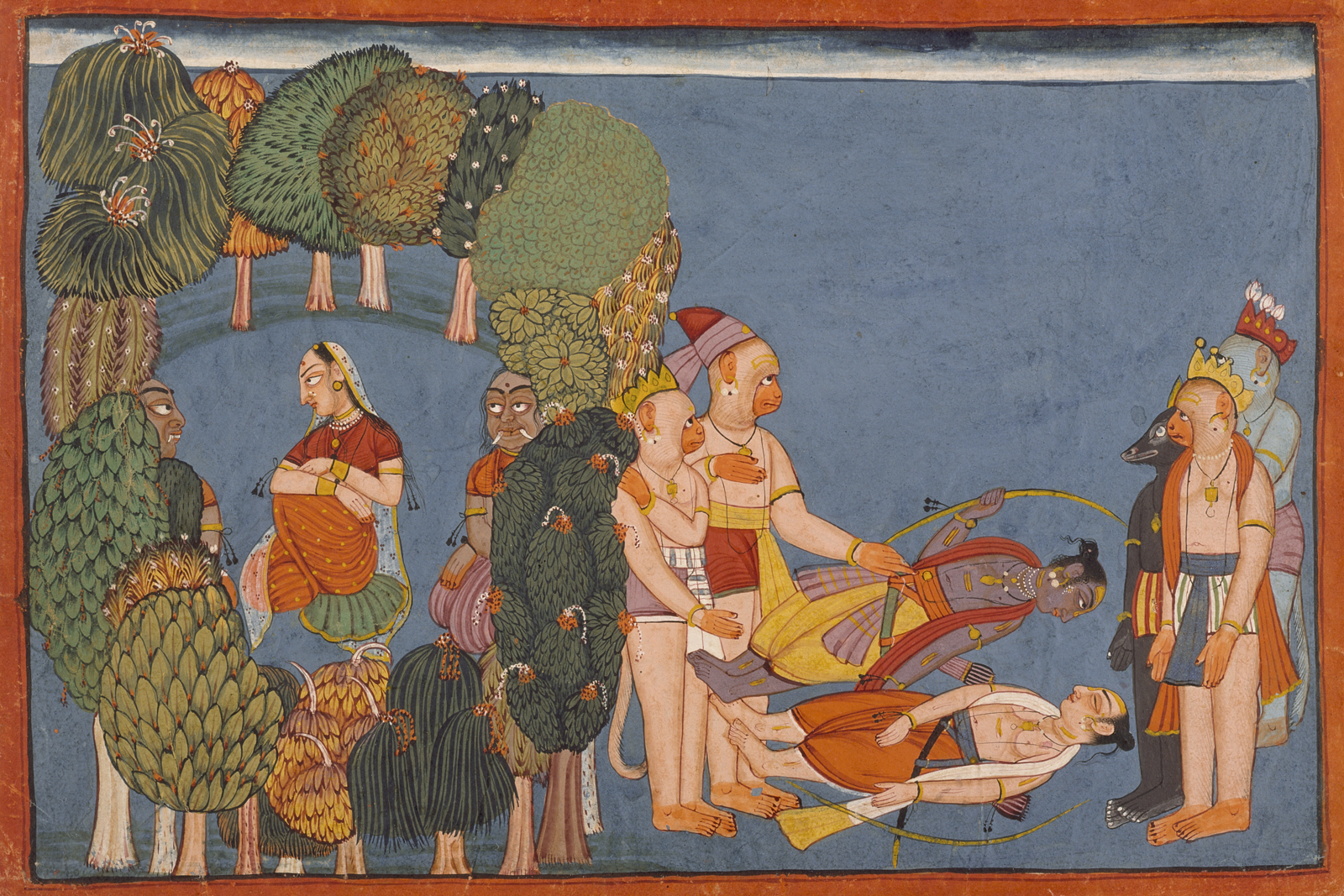

Goldman, a Sanskrit professor at Berkeley, recently completed a translation of the seven volumes of Valmiki’s Ramayana with her husband, Robert Goldman, also a Sanskrit professor at Berkeley. The 2,000-year-old epic, longer than The Odyssey and as old as the Bible, tells the story of Rama, an avatar of Vishnu. He is exiled by his father to the forest, his wife Sita is abducted by the demon Ravana, and Rama gets Sita back with the help of Hanuman, a monkey warrior. When Rama rescues her, he doubts her fidelity after being held captive in another man’s house, and Sita demands a fire trial to prove her loyalty. The epic is still wildly popular today, and when Indian college students were asked in the 1980s who’d they most like to be like, they overwhelmingly chose Sita—men as well as the women. When Goldman heard that, she wanted to investigate why that was. Sita is a multidimensional figure, she says, not a silent, dutiful person as she is often presented.

For many years, Goldman, who got her Ph.D. in Sanskrit at Berkeley in 1979 and has been teaching there since 1981, has been drawn to exploring gender in narratives. She has written several papers on Sita, as well as on Draupadi, a heroine from the epic Mahabharata. Goldman sees Sita as having strong opinions and her own voice.

“In the modern construction, Sita is the perfect wife and always obedient, but that’s not true at all—she has a lot of spunk, and when Rama is exiled, she’s not at all polite, and she says I want to go, and her language gets very abusive,” Goldman said. “She also articulates a voice of nonviolence against Rama when he talks about doing violence and she has some wonderful speeches that are very moving. In the fifth book, she has a long soliloquy trying to decide if she should kill herself or not. She uses very nuanced language that we can all identify with.”

Goldman grew up in Newport Beach and loved language, going on to study linguistics at California State University in Fullerton. She liked Latin, and then someone dared her to study Sanskrit, which she fell in love with. Berkeley had just opened its department in South and Southeast Asian Studies when she was looking for a place to do graduate work, and they had some wonderful professors, Goldman says. She remembers there was a lot more yelling at students then—but she was delighted with her choice to go to Berkeley.

“There’s so many things I like about Berkeley,” she said. “It’s a world-class public school, and I believe in public education. It’s always had a population that’s wonderfully diverse. As a teacher, I’ve had students from all over the world.”

Forrest McGill, the curator of South and Southeast Asian Art at the Asian Art Museum and the chief curator for the show, says Goldman’s articles about Sita and her voice have changed his views.

“Sita seemed kind of passive and doing her wifely duty,” he said. “Sally’s work has allowed me to see Sita as an agent in what is happening. Sally has helped me broaden and deepen and complicate my shallow perception of Sita.”

McGill says he has been in touch with the Goldmans, both of whom are international specialists in The Ramayana, about the exhibition for the last four years or so. Their help in explaining the story and the artwork has been invaluable, he says.

“Besides being a superb scholar and a person who’s thought through these issues thoroughly and profoundly, Sally’s also an enthusiast, and I’ve appreciated her willingness to swap emails at 11 at night,” he said. “Her dedication and enthusiasm and passion have been inspiring for all of us.”

Goldman is definitely enthusiastic about the show and its 135 pieces of sculpture, paintings, masks and puppets. The way it’s laid out, she says, with a focus on the four main characters—Sita, Rama, Hanuman, and Ravana—means everyone can enjoy it.

“It’s brought all these incredible pieces together, many of which I’ve never seen,” Goldman says. “It’s set up in a way so it’s accessible and meaningful. If you know nothing about the work, you can get a lot out of it, and for academics, they can see it at a different level. I’ve been to a lot of shows that are either so simplistic, you don’t even want to look at it, or that assume you already know so much. This has done a wonderful job telling the story from the perspective of each character.”